Two new Hans Blumenberg books are out in English translation, both short: Paradigms for a Metaphorology (and Care Crosses the River (1987). The second one is more aphoristic than anything else I’ve read by him and seems very mysterious at first glance (Stanford’s back-cover comment about how this book “eschews academic ponderousness” is probably not going to help capture the audience they desire). Metaphorolgy is dauntingly abstract but less abstruse, though I’m surprised exactly how much Blumenberg had worked out aspects of his “system” at this early point. This paragraph in particular, from the introduction, seems to be as concise a statement of his concerns as any:

These historical remarks on the ‘concealment’ of metaphor lead us to the fundamental question of the conditions under which metaphors can claim legitimacy in philosophical language. Metaphors can first of all be leftover elements, rudiments on the path from mythos to logos; as such, they indicate the Cartesian provisionality of the historical situation in which philosophy finds itself at any given time, measured against the regulative ideality of the pure logos. Metaphorology would here be a critical reflection charged with unmasking and counteracting the inauthenticity of figurative speech. But metaphors can also–hypothetically, for the time being–be foundational elements of philosophical language, ‘translations’ that resist being converted back into authenticity and logicality. If it could be shown that such translations, which would have to be called ‘absolute metaphors’, exist, then one of the essential tasks of conceptual history (in the thus expanded sense) would be to ascertain and analyze their conceptually irredeemable expressive function. Furthermore, the evidence of absolute metaphors would make the rudimentary metaphors mentioned above appear in a different light, since the Cartesian teleology of logicization in the context of which they were identified as ‘leftover elements’ in the first place would already have foundered on the existence of absolute translations. Here the presumed equivalence of figurative and ‘inauthentic’ speech proves questionable; Vico had already declared metaphorical language to be no less ‘proper’ than the language commonly held to be such, only lapsing into the Cartesian schema in reserving the language of fantasy for an earlier historical epoch. Evidence of absolute metaphors would force us to reconsider the relationship between logos and the imagination. The realm of the imagination could no longer be regarded solely as the substrate for transformations into conceptuality–on the assumption that each element could be processed and converted in turn, so to speak, until the supply of images was used up–but as a catalytic sphere from which the universe of concepts continually renews itself, without thereby converting and exhausting this founding reserve.

Remember, Blumenberg thinks of Descartes (at least in Legitimacy of the Modern Age) as a somewhat reactionary thinker who ignores the experimental and proto-scientific mindset of Nicholas of Cusa and Giordano Bruno in order to think of the world as a rarefied, perfect realm of method. He’s not the caricature that so many contemporary theorists use to trash the entirety of modernity, but a philosopher who seeks refuge in a form of theological thought that had already broken down, Scholasticism. So here, I think, Blumenberg projects mythology and irreducible metaphors as ‘leftover’ aspects of the world that prevent Descartes’ absolutist thought from fully encompassing it. And the more fundamental the metaphors are, the more important the historicism becomes.

Anyway, I find it rough-going.

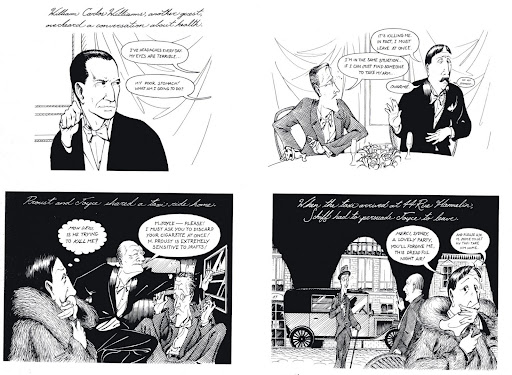

Care Crosses the River does have a nice little write-up of the infamous meeting between Joyce and Proust, which Tim Kreider dramatized in The Comics Journal [click to enlarge]:

![edgard_varese[1]](http://www.waggish.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/edgard_varese1.jpg)