Oh Erictho, where do I even begin? Driven seemingly by a desire to top what had gone before, Lucan continues to astonish as the poem goes on, and Erictho is his trump card. Erictho is a witch—the witch, in fact—and her underworld sequence at the end of Book VI has been called both the worst and the best section in the book. It’s definitely one of the most extreme, if only because Lucan comes off as exceptionally self-conscious, piling on the gratuitous horrors far beyond the point where most anyone would stop. But because Lucan is inspired, he pulls it off. What he pulls off is uncertain, but even in translation, the section bears its weight.

As a description of Erictho’s excess, I can’t do better than W.R. Johnson, who terms Erictho a hero of Civil War alongside Caesar, Pompey, and Cato:

She is enormously pleased with the satanic discors machina. She knows exactly how to operate it, and her prayers to it, unlike Lucan’s prayers to more traditional numina, are invariably answered in her favor. For her, doing bad things to good people, or even to bad people, or to any one at all—virtue and vice do not engage her imagination—is fun.

She shows an inexhaustible fullnes of life and an unwearying zest for malicious and purposeless activity that remind me of two of my other favorite characters: Stendhal’s DR. Sansfin and the early-middle Donald Duck. She is something fairly rare outside, say, the dark farces of Ben Jonson or the savage and surreal animated cartoons of the 1930s and early 1940s: a living caricature of wickedness, a pure distillation of frenetic immorality.

W.R. Johnson, Momentary Monsters: Lucan and His Heroes

Two points he makes bear repeating. The first is that Erictho has no particular ulterior motive, but is more just a animistic force, so much like the universe. The second is that where other seers and pythia claim to have power and knowledge but can’t make good on it, Erictho occupies a place above the gods and even above Caesar, blithely in control of the forces of the universe. Not that Erictho does all that much with her power. Indeed, we hear more about Erictho than we see her doing anything.. She’s not an influential force on the poem’s plot per se, just a envoy of the horrific universe surveying the action.

See here for some fascinating background on the myths behind Erictho. It also appears that Neil Gaiman appropriated Erictho’s techniques in the Sandman’s A Game of You serial.

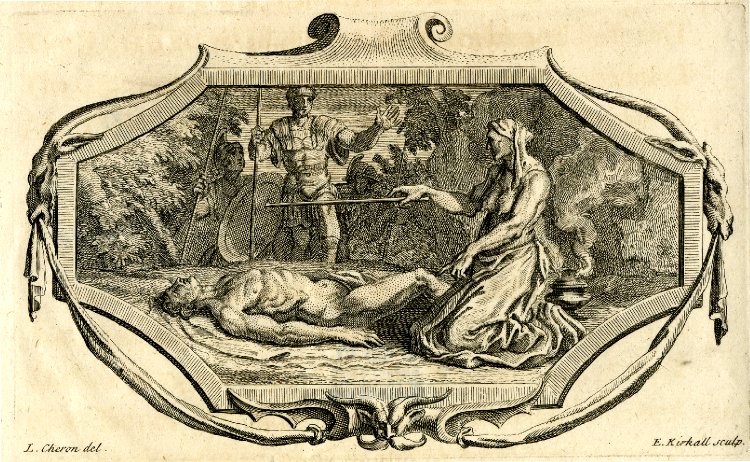

Pompey’s undercharacterized son Sextus goes to Erictho in Thessaly in the hopes of finding out the future. A long and very theatrical setting of the scene occurs:

Whenever black storm clouds conceal the stars,

Thessaly’s witch emerges from her empty tombs

and hunts down the nightly bolts of lightning.

Her tread has burned up seeds of fertile grain

and her breath alone has turned fresh air deadly.

She doesn’t pray to gods above, or call on powers

for aid with suppliant song, or know the ways

to offer entrails and receive auspicious omens.

She loves to light altars with funereal flames

and burn incense she’s snatched from blazing pyres.

At the merest hint of her praying voice, the gods grant her

any outrage, afraid to hear her second song.She has buried souls alive, still in control

of their bodies, against their will death comes

with fate still owing them years. In a backward march

she has brought the dead back from the grave

and lifeless corpses have fled death. The smoking cinders

and burning bones of youths she’ll take straight from the pyre,

along with the torch, ripped from their parents’ grip,

and the fragments of the funeral couch with smoke

still wafting black, and the robes turning to ashes

and the coals that reek of his limbs. But when dead bodies

are preserved in stone, which absorbs their inner moisture,

and they stiffen as the decaying marrow is drawn off,

then she hungrily ravages every single joint,

sinks her fingers in the eyes and relishes it

as she digs the frozen orbs out, and she gnaws

the pallid, wasting nails from desiccated hands.Civil War VI.579-606

Sextus flatters her, and she eats it up, happily resurrecting a corpse to report the news of the future. We are far from what the scene’s obvious antecedents, the underworld scenes in Book VI of the Aeneid and Book XI of the Odyssey, both of which come just before the midpoint of each epic and both of which result in auspicious findings for the heroes. (It’s not certain that the Civil War was to be twelve books long, but Books VI and VII feel very much like the heart of the poem, and general consensus has it at twelve.)

Here the underworld is not so mysterious or helpful. Erictho overshadows it completely. Erictho even tells Sextus that there’s nothing scary about her necromancy.

“If indeed I show you swamps of Styx and the shore

that roars with fire, if by my aid you’re able

to see the Eumenides and Cerberus, shaking

his necks that bristle with snakes, and the conquered backs

of Giants, why should you be scared, you cowards,

to meet with ghosts who are themselves afraid?”

When the corpse fails to resurrect, though, she throws a tantrum, and threatens the entire heavans and underworld at length. For me this is her greatest moment:

“And against you,

worst of the world’s rulers, I’ll send the Titan Sun,

bursting your caverns open and striking with sudden daylight. 830

Will you obey? Or must I address by name

that one at whose call the earth never fails to shudder

and quake, who openly looks on the Gorgon’s face,

who tortures the trembling Erinys with her own scourge

and dwells in a Tartarus whose depths your eye can’t plumb?

To him, you are the gods above; he swears, and breaks,

his oaths by waters of Styx.”

So who is this evil beyond evil whom Erictho has on quick-dial? Braund translates “that one” as “Him” (the Latin is just ille) and suggests as possibilities Demiurgus/Creator, Hermes Trismegistus, or Osiris or Typhon/Seti. I would love to know more about this when time permits, but it’s worth noting that, as explained in this old 1907 definition, Demiurgus was to become the evil Gnostic god himself in early Christianity:

Demiurgus, a name employed by Plato to denote the world-soul, the medium by which the idea is made real, the spiritual made material, the many made one, and it was adopted by the Gnostics to denote the world-maker as a being derived from God, but estranged from God, being environed in matter, which they regarded as evil, and so incapable as such of redeeming the soul from matter, from evil, such as the God of the Jews, and the Son of that God, conceived of as manifest in flesh.

I digress. Erictho is in touch with the genuine puppetmaster: not merely abstract Fortune, but the celestial watchmaker of the evil watch himself. She is unique in this regard.

Needless to say, the gods accede to Erictho’s threats and the corpse reanimates, but his report to Sextus is not especially helpful, hinting at the future but giving, ultimately, a shrug:

Don’t let the glory of this brief life disturb you.

The hour comes that will level all the leaders.

Rush into death and go down below with pride,

magnanimous, even if from lowly tombs,

and trample on the shades of the gods of Rome.

Which tomb the Nile’s waves will wash and which

the Tiber’s is the only question—for the leaders,

this fight is only about a funeral.Fortune is doling out tombs upon your triumphs.

O pitiful house, you will look on nothing

in all the world safer than Emathia.”Civil War VI.898-915

The future, then: you and your father and Caesar and everyone else will die. The Book ends without Sextus so much as responding. The corpse goes to rest, as promised by Erictho. So all the pageantry and drama, only to find out what we have known from the beginning, which is that all rulers and empires fall and die. In se magna ruunt: all great things crush themselves.

Erictho’s wickedness, in tandem with her lack of agency, make her a peculiar figure, simply because she is one of the very few characters in the book without much of an agenda in any direction. Even when she rails against heaven and hell, it’s on account of a “favor” she’s doing for Sextus, not any particular wish of her own.

It fits with the poem that the one character who may actually have some influence over the world’s events would be the character who never exercises that control in any meaningful way. (Her favor doesn’t amount to much, and she does explicitly say that she can only tell the future, not alter it.) Erictho is diabolical, but also oddly innocuous, at least within the poem. Stay far away from her, and she won’t cause you much trouble. Far less than the world, and Fortune, and Demiurgus will.

And as for the corpse’s predictions, I think not of Donald Duck, but of the Simpsons:

Psychic: [phone rings] Hello, "Radio Psychic"! You will die a terrible, terrible

death.

Marge: [on the phone] [gasps]

Psychic: Ooh, I'm sorry! That was our last caller. OK, I'm getting

something now. Hmm. OK: you will die a terrible, terrible

death.

Marge: But I --

DJ: Thank you for calling "Radio Psychic". Do you have a song

request?