The democratization and accessibility of knowledge has always been opposed by those who wish to keep power for themselves. These opponents may wish to be seen as wise authorities, or they may be fearful of the changes that will occur if people get too curious and too smart. Their weapon in disguising or confusing real knowledge is obscurity.

Obscurity can take several forms. Just a couple:

- Proclamations of secret inner knowledge and access to fundamental essences known only to a few.

- Accusations to others of ignoring the real truth at the heart of things.

- Deliberate obfuscation, hiding and/or complicating what is said in order to intimidate.

- Appeals to instinct and conventional wisdom to justify shaky reasoning.

All of these have been mixed in with quasi-religious rhetoric in order to reify the power-base of those who wish to be exempt from the strictures of rational inquiry and science.

(For those tempted to see this as religion-bashing, this actually has very little to do with religion per se. It is about rhetoric and power and authority.)

Not that science is exempt. Such techniques are sometimes used within science (string theorists have been guilty of this recently), but they have been used outside of it with far more vigor. The sheer consistency of this is shown by three examples each a century apart: Robert Fludd, J.G. Hamann, and Martin Heidegger. There is a fourth case too, a more recent one, who doesn’t quite fit the mold but merits inclusion: Saul Kripke.

It may seem unsporting or even perverse to point out this tendency when its advocates are so clearly on the losing side–at least among the cognoscenti. But unlike Scientology or Objectivism, the quasi-mystical obscure position needs criticism because so much real intelligence has fallen under its sway, possibly because its current underdog status masks the underlying hegemonic attitude of its proponents.

Also significant is that the underlying position hasn’t really changed that much: in each, a certain high-minded rhetoric is deployed with the signifiers of authority to do an end-run around the hard toil of more rigorous thinkers.

Four examples, then, from four eras: the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, Modernism, and today.

1. Robert Fludd (1574-1637)

Robert Fludd was an occultist and an exponent of the Hermetic traditions in the High Renaissance, just as Bacon, Galileo and Kepler were dismissing all sorts of superstition and trying to get a semi-coherent and semi-unified science off the ground. Unlike the far more brilliant Giordano Bruno, Fludd was simply not terribly bright, and in combination with colossal arrogance, he comes off as quite unpleasant.

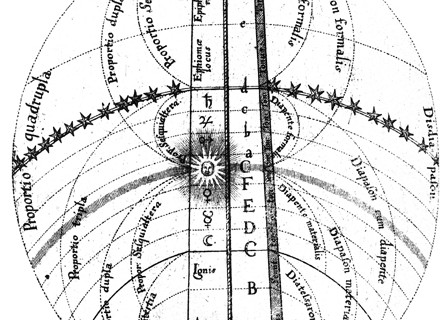

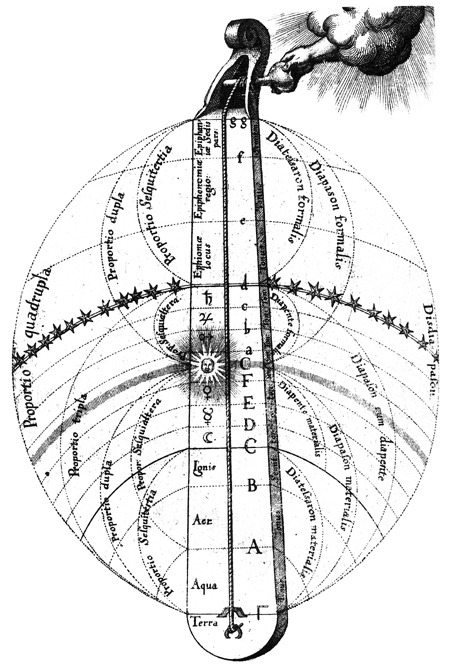

Fludd’s half-baked thinking, which led him to propose perpetual motion machines are best seen in his famous engraving The Divine Monochord, used on the cover of Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, among other places.

The engraving overlays the notes of the scale with Ptolemy’s circular orbits of the spheres. Even if you give him the geocentric universe, to which Fludd held half a century after the death of Copernicus, Fludd messed up the notes: the F should be an F sharp. Fludd was not one to worry about such things, and while the results may have artistic value, Fludd’s attempts to link them to physical phenomena are laughable. But this he did.

For Fludd, the mere stipulation of symbolism is enough to make something true:

Further, all kinds of natural things, and those which are supernatural, are bound together by particular formal numbers. The mystery of these occult numbers is best known to those who are most versed in this science, who attribute the Monad or unity to God the artificer, the Dyad or duality to Aqueous Matter, and then the Triad to the Form or light and soul of the universe, which they call virgin.

That is, numbers have special powers given to them by their “formal” nature, that is, their nature beyond mathematics. The analogies for numbers proposed by occultists lend the numbers real power, in Fludd’s view. Well, as Hans Blumenberg said, analogies are not transformations.

Fludd was an Oxford graduate and finally entered the College of Physicians after six failed attempts. Connections to the royal physician may have helped. Fludd became famous for his debates with Kepler, who was easily the most mystical of the scientists and astronomers.

Though Kepler had made his name by predicting a notoriously cold winter in 1595, Kepler distrusted astrology and generally held the more superstitious arts like alchemy and divination in total contempt. Nonetheless, he sought a cosmological union of mathematics, physics, and music that would explain the complete and utter perfection of God’s world. In the process, he correctly theorized that the orbits of the planets were ellipses rather than circles, a discovery of gobstopping genius contrary to pretty much what everyone everywhere had ever thought, and even more amazing given the lack of any theory of gravity to explain why the orbits were ellipses. He also discovered two other laws of planetary motion of similar import.

Fludd, in words that sound eerily contemporary (and not for the better), attacked Kepler as vulgar and scientistic, in a prolix pamphlet that needs to be heavily summarized:

In the arrogant pose of the esoteric and mystagogue Fludd lectured to Kepler, reproaching him for crass ignorance and ambition. Kepler’s science, in Fludd’s opinion, refers only to the outside of things. A distinction must be made between vulgar and formal mathematics. Only the chosen sages, skilled in formal mathematics, perceive nature truly; to the representatives of vulgar mathematics, among whom he also counts Kepler, and whom he calls bastards and stunted people, it remains invisible and hidden. These measure only the shadows instead or the reality or things. Fludd compares Kepler’s astronomy to a “mystical astronomy.” While Kepler stopped short with the outer movements of nature, he himself contemplates the inner and fundamental acts, which flow forth from nature. So it goes on, on fifty-four thickly printed folio sheets.

These samples from Fludd’s pamphlet are characteristic of the intellectual temper of that epoch. One who looks about in that departed era of writing and printing is astonished at the flood of astrological, alchemical, magical, cabbalistic, theosophic, mock mystic, and pseudoprophetic writings which held the intellects in a spell. The vaguer their content and the richer the promises they ventured in predictions, in communication of secret knowledge and abilities, the more readers they found. What was always being proclaimed under the name of Hermes Trismegistos passed for revelation, whereas imitation of the ideas of Paracelsus passed as the highest wisdom.

When Fludd, in the delusion of possessing deeper perception, held forth that he himself had the head in his hands, Kepler only the tail, then the latter replied humorously: “I hold the tail but with the hand; you clasp the head, if only it does not happen just in a dream.” The widdy disseminated writings, aiming to found and extend the order of the Rosicrucians, were naturally also known to Kepler. Yet he wanted to have nothing to do with a secret organization which feared the light. He urged the Brothers of the new order not to turn only to the ”children of the truth,” but also to go and to talk in the meetings of people, on the mountains and in public places, so that people would get to know their true doctrine.

In the face of all such pseudoscientific efforts, Kepler most strikingly characterized his manner of thought and the goal, which he also pursued in the Harmonia, when he says about his connection with Fludd: “One sees that Fludd takes his chief pleasure in incomprehensible picture puzzles of the reality, whereas I go forth from there, precisely to move into the bright light of knowledge the facts of nature which are veiled in darkness. The former is the subject of the chemist, followers of Hermes and Paracelsus, the latter, on the contrary, the task of the mathematician.” Fludd answered Kepler’s apology once more. The latter, however, did not want, as he says, to press this issue any longer and was silent. “I have moved mountains; it is astonishing how much smoke they expel.”

Max Caspar, Kepler: A Biography

Kepler only sees the outside of things, while Fludd penetrates to their innards. We’ll hear that line again.

Kepler eloquently described how Fludd “inner workings” terminally confused the causal workings of things with symbology:

I too play with symbols and have planned a little work, Geometric Cabala, which is about the Ideas of natural things in geometry; but I play in such a way that I do not forget that I am playing. For nothing is proved by symbols; things already known are merely fitted [to them]; unless by sure reasons it can be demonstrated that they are not merely symbolic but are descriptions of the ways in which the two things are connected and of the causes of these connections.

Brian Vickers draws the contrast quite vividly, emphasizing the replacement of Fludd’s visual constructions with Mersenne and Kepler’s primarily mathematical ones:

Mersenne rejects much of the conceptual structure of occult science, the whole analogical-correlative method, its symbolism, its confusion of mental and physical worlds….Kepler, by contrast, believed that the principles defining the structure of reality are picturable only in a certain sense. What is entirely lacking from the Fludd mentality is any interest in measurement or in testing an analogy against data derived from experience, and in this respect Kepler’s assumptions and methods are wholly different. The crucial issue is the relationship between pictures, words, and things. Fludd starts with ideas and pictures, finds words to describe them, and then links this composite to reality. Kepler, who deals with reality in terms of geometry, rejects Fludd’s analogies as visual or rhetorical, never capable of demonstration and often arbitrary.

Brian Vickers, Occult and Scientific Mentalities in the Renaissance

The particular method I’ve highlighted in bold is one that will recur as well.

Fludd was not well-liked. Even the alchemist Johannes Baptista van Helmont disparaged him as ‘a poor physician and a still poorer alchemist, talkative, loud, thinly learned, inconsistent . . . a fluctuating Fludd.’ And when you’ve lost the alchemists….

Frances Yates, generally rather sympathetic to the Hermetic tradition and its influence on the development of science, says this about him and Kepler:

Nevertheless, Kepler had an absolutely clear perception of the basic difference between genuine mathematics, based on quantitative measurement, and the “Pythagorean” or “Hermetic” mystical approach to number. He saw with the utmost distinctness that the root of the difference between himself and Fludd lay in their differing attitude to number, his own being mathematical and quantative whilst that of Fludd was Pythagorean and Hermetic. Kepler’s masterly analyses of this difference in his replies to Fludd brought this matter out into the clear light of day for the first time and performed a great service in finally releasing genuine mathematics from the agelong accretions of numerology.

Frances Yates, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition

Accretions can still accumulate, however.

2. J. G. Hamann (1730-1788)

J. G. Hamann was a lesser-known philosopher of the Enlightenment who had connections with Herder and Kant. Isaiah Berlin calls Hamann the first anti-rationalist opponent of the Enlightenment, though most of his substantive criticisms had been made already by people within the Enlightenment, so his influence is debatable. Hamann heavily protested against the anti-religious, scientific trends of his age, without articulating a particularly clear alternative beyond God.

What is not debatable is Hamann’s pioneering efforts into obscure, allusive writing. Unlike Kant, who writes densely but does not seem to be covering his tracks, Hamann takes pains to avoid saying much of anything directly. Sarcasm and ridicule are more his style than sincerity or cogency.

He engages in mystical investigations reminiscent of Fludd, such as his New Apology of the letter h. It is uncannily proto-Derridean in its punning half-fatuousness, as Hamann attacks a proposed spelling reform to standardize German by removing some silent letters. The proposal is not just wrongheaded, Hamann says, but blasphemous:

The canon of writing no letter which is not pronounced is the most impossible and exaggerated postulate in the exercise. Why is the author himself unfaithful to his own propositions, not only in regard to all the other letters, but even to h? Why does he not write in instead of ihn, and inn instead of in, or ir instead of ihr, and tun instead of thun, in order to comply at least with the appearance of an analogy? What reason can indeed be envisaged for his biased exception of all the remaining letters and his unjustified severity toward a breath, which is not even an articulated sound?

If the pronunciation of letters is to be elevated to a universal judgment throne over correct spelling such as the one so-called human reason arrogates to itself (under cover of liberty) over religion, then it is easy to foresee the destiny of our maternal language. What divisions! what Babylonian confusion! what mongering of letters! All the great diversity of dialects and speech and their shibboleths would pour into the books of each province, and what dam could withstand this orthographic deluge? The h, turned out from the raw midnight of Germany, would prolifherate [sic] itself in the writings of the greater and milder nations of the Holy Roman Empire with such opulence that would not be comparable to the wise generosity of a famous translator of sacred parchment rolls in very isolated cases. – In short, the whole social bond of literature among the German nations would be destroyed in a few years, to the great disadvantage of the true, universal, practical religion, its dissemination, and the peace promised by it – –

J. G. Hamann, “New Apology for the Letter h” (1773, tr. Kenneth Haynes)

I suppose this is good fun, but I find it rather tiring and trivial for a supposed major work, though Haynes is to be commended for assembling a reasonably compact and accessible collection. His sneering at “so-called human reason” and the elevation of his stipulated “true, universal, practical religion” grate. I’m more inclined to agree with Michael Forster’s view of the impoverishment of Hamann’s philosophy:

Besides being unsystematic, Hamann’s writings are typically short; occasional in nature; adorned with mysterious visual symbols (e.g. the figure of Pan), and enigmatic titles, subtitles, and mottos; authored with an adoption of strange identities; extremely obscure in content; lacking in developed argument; full of quotations from ancient and modern works left in their various original languages, as well as citations and allusions, many of whose significance is left unclear; prone to the use of German archaisms, especially the vocabulary and constructions of Luther’s German Bible; bombastic and dramatic; crude, sometimes to the point of obscenity; humorous and satirical, often in cruel ways; and rich in metaphors. As Goethe already observed, the cumulative effect of such features (especially for a modern reader deprived of the help that was supplied by the contemporary context) is to preclude satisfactory understanding.

Hamann did not have to write in this way; his early Biblical Reflections, a long work, is written clearly and even elegantly, and his letters throughout his life often show similar virtues. Why, then, did he choose to write in this way? Part of the explanation lies in his principled contempt for reason, and therefore for the conventional ways of writing that rely upon it. Another part of the explanation lies in a deep disaffection with his age and its ‘‘public’’—rooted in his unpopular religious position, but also exacerbated by more mundane grievances, including, for example, his lowly employment and inadequate salary—which leaves him uninterested in being understood by most of his contemporaries, and indeed keen to mystify them. Yet another part of the explanation lies in a motive that is in tension with the preceding one: a wish to cultivate a strikingly distinctive authorial individuality. Yet another part of the explanation lies in a fear that his ideas were not original or cogent (in his letters he voices a fear that he got all his main ideas from the poet Edward Young, and laments the weakness of his own intellect, e.g. in comparison with Kant’s), and in a resulting desire to mask his intellectual nakedness. It is difficult to have much sympathy with these motives.

Michael Forster, After Herder: Philosophy of Language in the German Tradition

Contra Socrates, Hamann thinks self-knowledge is “a descent into hell,” merely painful preparation for the real truth of salvation. So Hamann is really opposing not just the intellectual trends of the time but the use of reason as a means to anything but faith. The obscuritanism and the attacks on reason go hand in hand with Hamann’s appeal to religion (Christianity, of course), and so it is not so surprising that today he is being used by postmodern theologians to help expand the gaps in which they wish God to exist. That is to say, postmodernism not in the service of skepticism or pluralism, but in service of ignorance and superstition.

John Betz enthusiastically endorses Hamann’s attack on Kant and the claim that Kant’s system is really just another religion like any other, Kant a “magician” and “alchemist” playing tricks on us:

Indeed, following Hamann, the very structure of Kant’s Critique could be said to mirror the mystagogy of the temple cult, proceeding by way of an ever more inward progression from the forms of intuition, which concern the “outer court” of sensibility, to the “sanctuary” of the transcendental categories of the understanding, to the sanctum sanctorum of the regulative ideas of reason itself.

In any case, as Hamann reads it, the Critique is a kind of “magical mystery” tour de force. Kant’s philosophy is “alchemical” because its transcendental method involves a similar process of purification; the only difference here is that the “dross,” which must be separated in order to attain the “philosopher’s stone” is phenomenal experience.

John R. Betz, After Enlightenment: Hamann as Post-Secular Visionary

Teach the controversy! Kant’s philosophy, whatever its many problems, is not alchemical and not a temple cult. I repeat again: analogies are not transformations. Betz seems to think that Hamann has some sort of knock-down arguments, and that these knock-down arguments, having God in them, are somehow superior to all other criticisms against Kant and deserving of more attention.

Betz sides with Hamann in his attack on Herder’s pioneering naturalist account of the origin of language. I will not get into why Hamann’s criticisms of Herder are weak and specious (Forster’s book addresses this issue convincingly), since the rhetoric is my focus here. Note how Betz goes right along with Hamann’s invective precisely when it is most free of content:

In a masterful stroke of irony Hamann then adds that Herder’s “natural” theory must have been the product of divine inspiration, due to a divine “Genesis”; indeed, it must be even more supernatural and poetic than the oldest account of the creation of heaven and earth. For, surely, only inspiration would cause this learned author to set himself up “so confidently and so recklessly for such public, earth-shaking, hyperbolic-pleonastic, retaliatory criticism, and to misuse polemical weapons only to incur wounds and lumps at his own expense, accomplishing thereby precisely the opposite of what his readers are promised and flatteringly led to expect.”

What a lashing!

With consummate irony, Hamann then caps his parody with the following coup de grace: “With this divine organon of understanding the entire Koran of the seven [liberal] arts and the entire Talmud of the four faculties was invented, and upon this rock stands the fortress of the philosophical faith of our century, before which all the gates of oriental poetry must submit.” That is to say, how can this understanding of the origin of language, which rests upon a plain contradiction, possibly serve as a suitable foundation for philosophy, for the sciences, for philology?

What a damning appraisal!

John R. Betz, After Enlightenment: Hamann as Post-Secular Visionary

I find it vaguely frightening that such rhetoric as Hamann’s should appear so convincing to a theologian that it could be cited with such cheerleading enthusiasm. Betz’s choice of the phrases “lashing” and “damning appraisal” are rather intriguing on their own, but that’s left as an exercise for the reader.

It should not, then, come as too much of a surprise that Betz then links Hamann to Heidegger and Derrida and enlists all three in his religious project, finding fault with the latter two in that they are not sufficiently religious (i.e., Christian), making Hamann the clear choice:

Thus it comes about that for Heidegger, the anti-Augustine, paradoxically “Nothing” really “Is”; and that this “Nothing” becomes the source of ethics, revelation, and poetic inspiration. Such is the odd, uncompelling, and, in view of the horrors of the twentieth century, ethically chilling result of Heidegger’s attempt to purify philosophy of theology, whereby he essentially repeats in the realm of ontology the same fundamental error Hamann identified at the heart of Kant’s epistemology, thereby bringing the history of philosophy (divorced from theology) to its explicitly nihilistic conclusion.

After the Enlightenment, the problem of reason, following Hamann and now Derrida, has come down to the problem of language. In short, it comes down to a choice between inspired and uninspired language: either language inspired by the Holy Spirit in response to the Logos, or language inspired by Nothing at all.

John R. Betz, After Enlightenment: Hamann as Post-Secular Visionary

Here it is more difficult to argue with Betz, for he is opposing thinkers who have dispatched the only terms of argument that could help them against Hamann, and given the choice between Nothing and God, people will tend to plump for the latter. All of the relativism eventually gives way to the “true, universal, practical religion” of which Hamann, and presumably Betz, are certain.

3. Martin Heidegger (1889-1976)

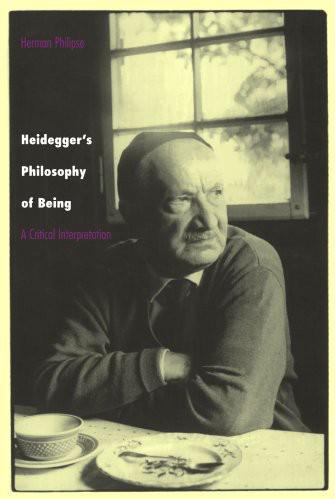

Much of the discussion of Heidegger can be found in the entry on Herman Philipse’s Heidegger book, where Philipse diagnosed Heidegger’s rhetoric as authoritarian and theological. (More on Heidegger’s sloppy scholarship.) Heidegger’s irritating statement “Only a god can save us” is ultimately representative of the tactics of his later work. I quote the relevant bits from the previous entry:

Sometimes Heidegger claims that he has a specific epistemic gift for discerning what Being sends us, and he compares those who do not have this gift to people who are color-blind. Unfortunately, this analogy with color-blindness does not withstand critical scrutiny. Color-blindness can be explained by specific defects in our visual apparatus, whereas I suppose that the inability to grasp what Heidegger claims to be discerning cannot be so explained. Heidegger relies on a epistemic model derived from theology, and assumes that he is the recipient of some kind of revelation…

What Heidegger counts on, then, is that we will simply believe what he says. He uses a number of authoritarian rhetorical stratagems in order to obtain this perlocutionary effect, and he is remarkably successful in securing it.

“History” in the habitual sense of the word designates both the sum of human actions, artifacts, and forms of life in the past, and the discipline that studies these actions and forms of life. Because Heidegger in section 7 of Sein und Zeit calls empirical phenomena “vulgar” phenomena, we might label empirical history “vulgar” history. To vulgar history, Heidegger opposes real or authentic history (eigentliche Geschichte), which is the sequence of fundamental stances underlying vulgar history. Real history is “necessarily hidden to the normal eye.” It is the history of the “revealedness of being” (Offenbarkeit des Seins). Heidegger’s later “historical mode of questioning” (geschichtliches Fragen) aims at making explicit fundamental stances of Dasein amidst the totality of beings. Since these stances allegedly can be studied independently of empirical history as an intellectual discipline, Heidegger’s doctrine of real history implies that the philosopher is the real historian, and that by reconstructing the sequence of metaphysical structures, he does a more fundamental job than the historian in the usual sense is able to do. Heidegger often intimates that his historical questioning is also more fundamental than historical research done by historians of philosophy, and that it may brush aside the methodological canon of historical philology and interpretation. As Joseph Margolis observes, Heidegger’s doctrine of real history “manages to ignore the concrete history of actual existence and actual inquiry.”

Heidegger belonged to the elect, to those favored by Being, who were destined to hear Being’s voice. In Beitrage zur Philosophie, the theme of the elect occurs again and again.

Herman Philipse, Heidegger’s Philosophy of Being

I trust that the linkages here are evident. Like Fludd and Hamann, Heidegger appeals to some sort of revelation to which he has privileged access, one that both trumps other accounts and is not accessible to them. The presupposition of having penetrated to the inner core of things is stated as a first principle, not a conclusion.

This passage from The Question Concerning Technology is representative:

In truth, however, precisely nowhere does man today any longer encounter himself, i.e., his essence. Man stands so decisively in subservience to the challenging-forth of enframing that he does not grasp enframing as a claim, that he fails to see himself as the one spoken to, and hence also fails in every way to hear in what respect he ek-sists, in terms of his essence, in a realm where he is addressed, so that he can never encounter only himself.

Martin Heidegger, “The Question Concerning Technology”

But Heidegger sees, Heidegger encounters. Heidegger knows the fundamental inners of things, like Fludd. His claims would be easily dismissed if technology and science didn’t present so many genuine questions that Heidegger is forcing out of people’s minds with his mystification. Such obfuscation neuters the rational force of any critique it is used to make and replaces it with pure authority. If you have the authority that Heidegger had, you can win the argument; if you don’t, you will lose.

4. Saul Kripke (1940- )

It may seem unfair and even perverse to include Kripke on this list, for unlike the others he has an indisputably great contribution to formal logic. Yet it is his metaphysics and his rhetoric with which I am concerned here, and I can’t deny the overlap. In fact, it’s significant that both an “analytic” and a “continental” philosopher can fall into this list.

Kripke does not use obscurity per se; what he does do is utilize a closed system that is then pushed onto reality. In this he resembles Fludd, who in Vickers’ words “starts with ideas and pictures, finds words to describe them, and then links this composite to reality.” The composite here is far more rigorous and “scientific” than anything Fludd ever managed, yet the outcome is not so different. Those who favor Kripke will certainly disagree, but the burden of proof remains with them. Central to Kripke’s approach is an appeal to ungrounded intuition that mimics the tactics of the above thinkers. Intuition becomes another obscuring tactic.

Kripke acolyte Scott Soames gives a non-technical summary of Kripke’s impact:

[Kripke’s theories] brought back the idea that things in the world have discoverable essences, which are properties not just physically required but metaphysically necessary for their existence. Some of these properties are discoverable by science. But these may not exhaust the essential properties of human beings. The impact of Kripke’s book was its message that, despite the progress philosophers have made in understanding meaning and language, philosophical knowledge is not limited to that, which means that philosophy must reconnect to the non-linguistic world.

Essential properties: the insides of things, just as Fludd claimed access to. The armchair discovery of essential properties beyond those discoverable by science is quite an achievement, one capable of generating a lot more business for philosophers itching to escape the punishing strictures of mid-century anti-essentialism. How did Kripke do it? Richard Rorty provides a good overview in the LRB, but I will briefly summarize the technical points:

Kripke postulated a formal modal logic for talking about possible worlds, creating a formalization of “necessary” and “contingent” propositions that has caught on like wildfire, wiping away the austerity of W.V.O. Quine and a number of other mid-century analytic philosophers in favor of bold new metaphysical conjectures. Some of these conjectures are indeed dangerously close to postulating the inner essence of things, as anyone who reads Kripke’s Naming and Necessity will realize. Key to this is Kripke’s idea of the “rigid designator,” a name that picks out the same thing in all possible worlds. Rigid designators include all proper names, various technical physical science terms. Somewhat famously, he says:

I thus agree with Quine, that “Hesperus is Phosphorus” is (or can be) an empirical discovery; with Marcus, that it is necessary.

So it is not possible that Hesperus could not have been Phosphorus, and this modal, metaphysical claim is based solely on the nature of the linguistic terms involved and the counterfactual possible world setup he has going. In response to those who complain about possible worlds, he says:

Those who have argued that to make sense of the notion of rigid designator, we must antecedently make sense of ‘criteria of transworld identity’ have precisely reversed the cart and the horse; it is because we can refer (rigidly) to Nixon, and stipulate that we are speaking of what might have happened to him (under certain circumstances), that ‘transworld identifications’ are unproblematic in such cases.

Saul Kripke, Naming and Necessity

The shorter version of this, again, is: saying makes it so. The way in which we use language somehow makes it possible to generate claims about metaphysical necessity. Can we rigidly refer to Nixon? That seems to be the shaky ground on which cart and horse must ride.

For someone like myself who thinks that simply naming something isn’t even sufficient to be certain it exists, Kripke is far off the mark, but again, that is beside the point here. My consideration here is with the rhetorical tactics involved and how they echo past thinkers who presume a familiarity with the inner nature of reality and use a certain sort of authoritative language to proclaim it.

Other Kripkean feats include proving the necessity of “Water = H2O” and “Cicero = the organism descended from sperm s and egg e,” as well as the non-necessity of “Mental events are identical with brain events.” The passage related to this last one is worthy of quoting. Here, “C-fibers” are the part of the brain that happen to be associated with pain in humans.

What about the case of the stimulation of C-fibers? To create this phenomenon, it would seem that God need only create beings with C-fibers capable of the appropriate type of physical stimulation; whether the beings are conscious or not is irrelevant here. It would seem, though, that to make the C-fiber stimulation correspond to pain, or be felt as pain, God must do something in addition to the mere creation of the C-fiber stimulation; He must let the creatures feel the C-fiber stimulation as pain, and not as a tickle, or as warmth, or as nothing, as apparently would also have been within His powers . . . The same cannot be said for pain; if the phenomenon exists at all, no further work should be required to make it into pain.

From here it is a short hop to Kripke’s personal views:

Kripke is Jewish, and he takes this seriously. He is not a nominal Jew and he is careful keeping the Sabbath, for instance he doesn’t use public transportation on Saturdays. He thinks religion can help him in philosophy:

“I don’t have the prejudices many have today, I don’t believe in a naturalist world view. I don’t base my thinking on prejudices or a world view and do not believe in materialism.”

He claims that many people think that they have a scientific world view and believe in materialism, but that this is an ideology.

Such remarks sound a bit condescending, and so I ask: does Kripke have his own prejudices? It seems that he does not. He is well above the rest of us, having evidently transcended the need for a worldview. And perhaps language as well:

“People used to talk about concepts more, and now they talk about words more,” he says, capsulizing the profession. “Sometimes I think it’s better to talk about concepts.”

Yet the reason for why analytic philosophers migrated to words was that no one could agree on what a concept was. Nor how to grasp one. The Stanford Encyclopedia entry on Concepts encompasses nearly every discipline of philosophy, while offering little that is uncontested save for the gnomic first sentence: “Concepts are the constituents of thoughts.” So the way I read Kripke’s statement is that people should talk about concepts his way.

Yet in justifying the correctness of his versions of things, Kripke often appeals to intuition. The word “intuition” appears frequently in Kripke’s writings, often as something he wishes to “capture” formally. The Preface to Naming and Necessity appeals to intuition on nearly every page in justifying rigid designators. The papers in Philosophical Troubles use intuition, if anything, more frequently, particular when speaking about truth and knowledge. Some form of the word “intuition” is used 246 times in the book’s 380 pages. For comparison, Quine uses it 9 times, and not always favorably, in the 130 pages of From a Logical Point of View, while Davidson uses it 23 times in the 285 pages of Inquiries into Truth and Intepretation. Wittgenstein uses it only four times in all of Philosophical Investigations, while Sellars makes only a single derogatory use of it in the entirety of Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind.

Now perhaps Kripke’s experience is different, but I live in a world in which the vast majority of intuitions that I or anyone else has are wrong. Today’s intuitions are tomorrow’s mockeries. Either way, I don’t see how you combat Kripke if you have an opposing intuition. I doubt he expects one to do so. Appeals to intuition in philosophy are not so different from appeals to feeling, consensus, or religion: they rely on you accepting an unsubstantiated claim from a supposed expert or authority. It is hard to see intuition as much more than an authoritative cudgel designed to shut down questions and let things remain cloudy. At the end of the day, I think this is what Kripke’s metaphysics will remain: ungrounded appeals to intuition.

In some ways Kripke has embraced obscurity, publishing next to nothing in the years since Naming and Necessity and cultivating an oracular persona. He is very much a counter-Wittgenstein, another religious philosopher who published almost nothing, yet where Wittgenstein leaves us with questions, Kripke is always in a hurry to give answers. I do believe that Kripke’s metaphysical system has more value than Fludd’s pretty but false pictures of the world, but I do wonder how much more value.

I’ll let Quine have the last word on intuition’s use as a core tool of mystic authorities:

Twice I have been startled to find my use of ‘intuitive’ misconstrued as alluding to some special and mysterious avenue of knowledge. By an intuitive account I mean one in which terms are used in habitual ways, without reflecting on how they might be defined or what presuppositions they might conceal.

W.V.O. Quine, Word and Object

And this dual nature of ‘intuition’ is why intuitions are obscure, and why they form the fundament of Fludd, Hamann, Heidegger, and Kripke’s work.

Benny Shanon is an Israeli cognitive psychologist who has taken the psychoactive hallucinogen ayahuasca well over one hundred times. His book The Antipodes of the Mind: Charting the Phenomenology of the Ayahuasca Experience is a scholarly attempt to describe its effects both through a survey of participants and through descriptions of his own extensive experiences.

Benny Shanon is an Israeli cognitive psychologist who has taken the psychoactive hallucinogen ayahuasca well over one hundred times. His book The Antipodes of the Mind: Charting the Phenomenology of the Ayahuasca Experience is a scholarly attempt to describe its effects both through a survey of participants and through descriptions of his own extensive experiences.