I thought Twin Peaks: The Return went far deeper than the original series. I wrote this prediction before the premiere about how Twin Peaks: The Return would function:

I expect the new season to be about “Twin Peaks”–not the town, but the show itself. The new season will wrap itself around the old show rather than continuing the plot.

Still, I was expecting The Return to wrap up with a bit more closure than it appeared to. Even though I was sure the end result would be closer to Inland Empire than the original show, I thought Frost’s presence as well as the sheer task of shaping 18 hours of material would require some sort of narrative arc simply to serve as an organizing principle. And it certainly seemed that way until the elliptical and incredibly desolate final episode, which I found viscerally disturbing like nothing else in Lynch’s oeuvre. (Even the three films of his I love, Eraserhead, Mulholland Drive, and Inland Empire, don’t move me like that final episode did; they’re more enveloping aesthetic experiences than emotional ones.)

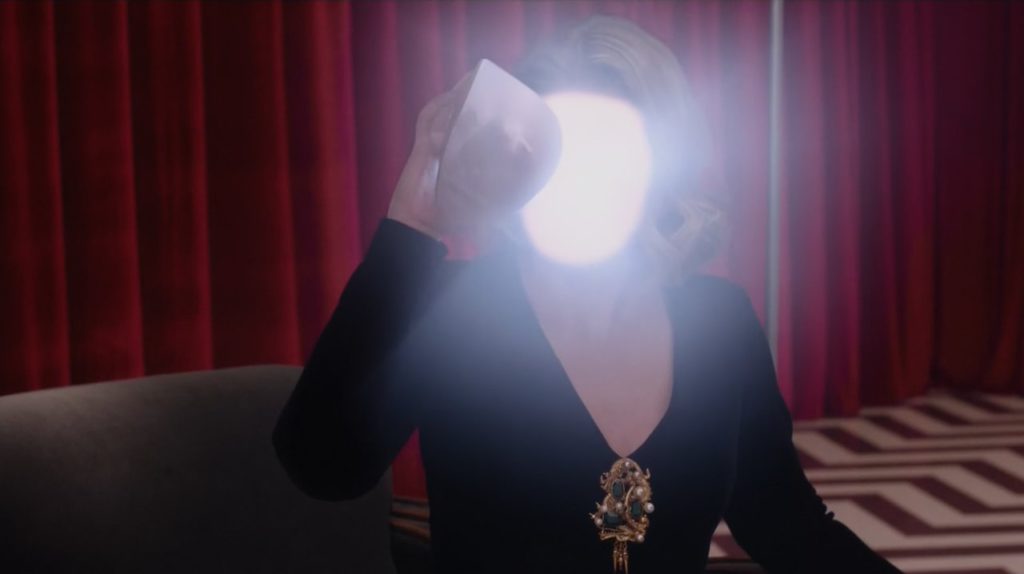

The Curtain Call

The creation of the all-encompassing sense of dread in the absence of any clear rationale or narrative is an awesome achievement. It’s so powerful, particularly the “love” scene between Cooper and Diane, that it demands some attempt at an explanation. This is my best surmise of the kind of submerged material Lynch built episode 18 on top of. My account was inspired by this poster’s key observation that the alternate world of episode 18 was created not by negative entity Judy, but by the White Lodge itself as a trap for Judy. It was the first explanation that began to hint at a reason for the peculiar, overwhelming pathos of the final episode, including the uncanny and unsettling sex scene between Cooper and Diane.

A few things to keep in mind:

- Neither the Doppelganger nor BOB is the primary antagonist of the season. Judy is.

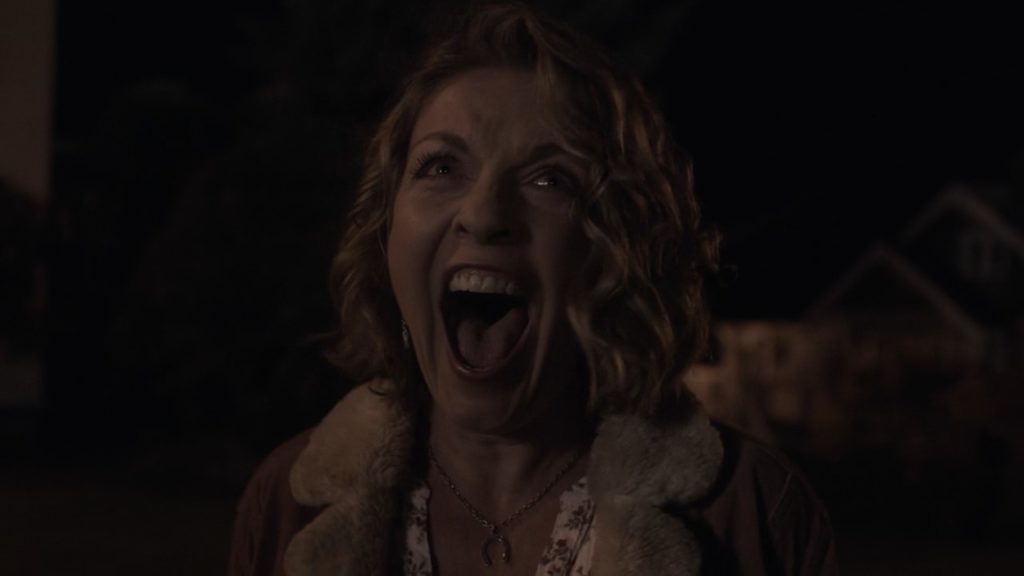

- Judy is or is represented by the Experiment monster, the Mother, horned bug symbols (Jeffries says as much), the Jumping Man, the Chalfonts/Tremonds, and Sarah Palmer.

- Gordon Cole, Garland Briggs, and Cooper have had some kind of longstanding plan to deal with Judy, in partnership with Phillip Jeffries and MIKE.

- Twin Peaks: The Return has a symmetrical structure. For example, Cooper enters catatonic Dougie-state 2.5 hours in and wakes up with 2.5 hours to go.

- Black Lodge creatures, including Judy, are attracted to pain and sorrow, a.k.a. garmonbozia, and consume it.

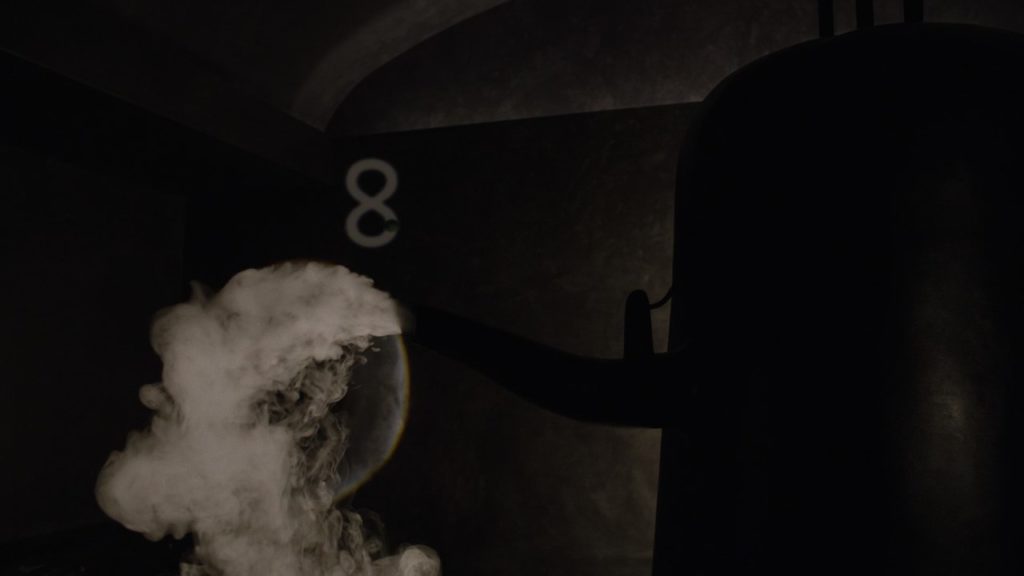

- Electricity is a fundamental energy, like fire.

Electricity

Here is my best guess at the plan to deal with Judy, and the terrible costs associated with it. None of this is meant to be definitive, just an approximation of something I find compelling, and perhaps an approximation of what Frost in particular had in mind before Lynch started improvising over it.

“You are far away.”

The Fireman tells Cooper in the very first scene, “It is in our house now.” The “it” is Judy and her Black Lodge denizens. The Fireman is never more serious than he is here. This is a very, very bad thing, requiring desperate measures. He then gives Cooper three reminders: 430 [miles to the crossover into the alternate reality], Richard and Linda [Cooper and Diane’s alter egos], and “Two birds with one stone” [Cooper’s plan]. The timing of this scene is ambiguous. It may take place after Cooper electrocutes himself back into sentience in episode 15, but it’s more important that Cooper remembers it after that point, and knows what he has to do.

The Bomb

The trap has three key elements:

- The Cage: a pocket dreamworld created by the White Lodge, containing Odessa, Texas and Twin Peaks

- The Lure: Cooper and Diane

- The Bomb: Laura Palmer

“It’s slippery in here.”

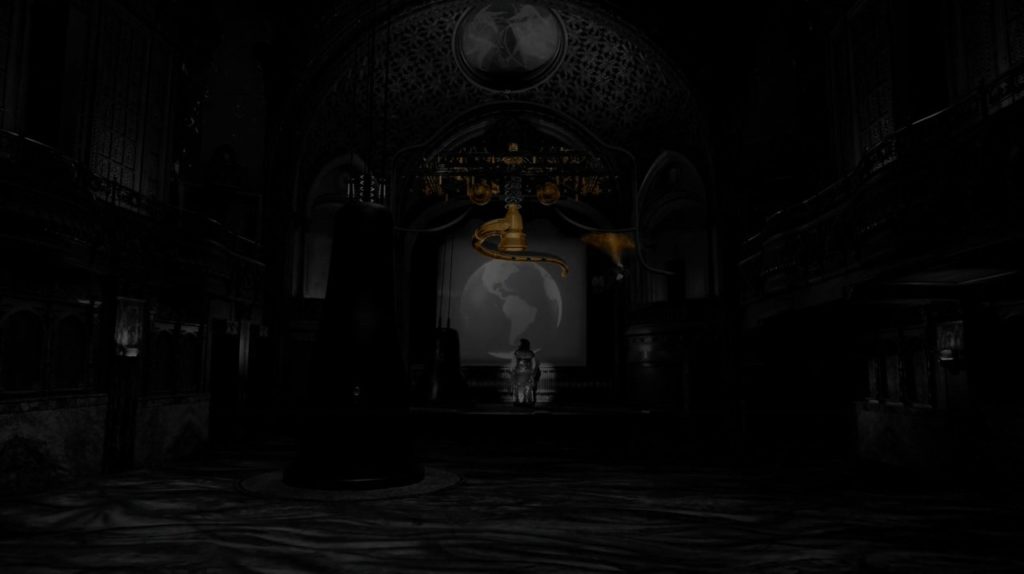

With Phillip Jeffries as travel agent, Cooper goes back in time to rescue Laura Palmer on the night of her death. He tells her, “We’re going home,” in a funny and not terribly reassuring tone of voice. If “home” means the home of her parents, it is about the last place Laura would want to go. In fact, “home” is the White Lodge, where Laura originated in episode 8. Cooper takes Laura to the Jackrabbit’s Palace White Lodge grove. The sound the Fireman played for Cooper is heard just as Laura Palmer disappears, screaming as she does. This signals that the White Lodge has picked her up. Cooper is not especially surprised at her disappearance. He looks up because she has been pulled up, as she was from the Red Room in episode 2 (with the same fluttering noise). Up is the direction to the White Lodge.

“We’re going home.”

Sarah, acting under the influence of Judy, is infuriated by Laura’s disappearance and tries to smash her picture, but the scene keeps rewinding and the picture is invulnerable. This reality is becoming the “unofficial version” and Laura is “saved.”

Homecoming

The White Lodge does “save” Laura from death at her father’s hands, but that’s not Cooper’s purpose, which is why he seems increasingly dour after leaving the sheriff’s station. Laura is being put to use in the trap for the greater good, but not for her own good. She has still suffered a terrible childhood and adolescence full of abuse. In Fire Walk With Me, Cooper told Laura not to take the owl cave ring because Cooper’s plan requires Laura alive. When Leland/BOB killed Laura, it messed up the plan.

If Cooper were primarily concerned with truly saving Laura, why didn’t he rescue her from the past years before the night of her death, in order to spare her so much terrible abuse? Ironically, the tragedy of Laura Palmer is that no one wanted her to die, yet everyone caused her to suffer—the revelation of episode 18 is that her tormentors now include Cooper among them. In The Return, “Who killed Laura Palmer?” ultimately becomes the MacGuffin Lynch and Frost originally intended it to be. The question “Who killed Laura Palmer?” led both characters and viewers astray, distracting from the more important and more compassionate question, “Who—or what—is Laura Palmer?”

The White Lodge deposits 1989 Laura into a pocket dreamworld, which I’ll just call the Cage. We already saw the White Lodge use a cage to contain Mr. C briefly; that is a hint as to the nature of this dreamworld. It shapes itself around her. Laura then stays in the Cage for 25 years, living out a mostly uneventful life as Carrie Page in Odessa, Texas.

Odessa, TX, Pop. Pylon

Laura’s subsequent life as Carrie Page appears to have been better than her childhood, judging by what little we learn of her, but there is still a dead body in her living room when Cooper shows up. The Cage is, perhaps, Laura’s dream of the life she hoped to have if she could escape her childhood. By entering the Cage, she forgets much of what happened prior to entering it.

The Cage is not Judy’s domain. It is a White Lodge creation given shape by Laura’s own dreams. The jackrabbit is the symbol of Odessa. The Fireman knew of the Cage by the time Andy took his trip into the White Lodge: he showed Andy a picture of the #6 pylon outside Carrie Page’s house. The Fireman is conscious of the plan and an accomplice to it.

Fireman-o-vision

“Laura is the one,” but why? When the Fireman sent the golden Laura orb down to Earth in response to the Trinity nuclear test, I and others worried that this might change Laura from a fully human survivor of abuse into some sort of magical chosen one, dampening the human element of the show. I now think that Laura is special, but she is special because of her pain. Laura lives through a horrendously dark youth. The psychic residue left by her abuse at the hands of her father and BOB is so tremendous that Judy makes the Palmer house her base of operations, either inhabiting or possessing Sarah Palmer. BOB was a garmonbozia glutton, and Laura was an everlasting gobstopper of garmonbozia, until she died (an outcome which BOB/Leland did not want). The Black Lodge consumes garmonbozia, but cannot generate it independently.

Deployment

Why would the Fireman, portrayed as a positive figure, create such a martyr figure? I suggest that Laura Palmer was meant to function as a capacitor: storing a huge accumulated charge of suffering which could then be discharged at the precise moment. Laura’s immense suffering does not make her superhuman, but it makes her uniquely capable of serving a purpose in the Trap. In the right setting, this discharge could overload the circuits of a Lodge entity and destroy it altogether. To use another apt analogy, it would be like an atomic bomb reaching critical mass. But with fissionable material as substantial as Judy, you would not want to detonate it in our universe, or else it would take most of our world with it.

Judy’s Life-force

In the language of Hawk’s map:

- Laura is the highly-concentrated pure corn (of fertility) that becomes diseased black corn (garmonbozia) through suffering.

- Black Lodge beings consume garmonbozia to generate black fire/electricity (which smells like scorched engine oil).

- Judy is the powerful mother of corrupted fertility, capable of consuming unearthly amounts of garmonbozia to feed her immense black flame.

- Given sufficient black corn (i.e., fuel), the black fire will grow, consume everything, and burn itself out, like pouring gasoline on a fire. Or an electrical circuit overloading. Or an atomic bomb reaching critical mass.

Highly concentrated, highly flammable, but still too pure

Gold is the color of garmonbozia, and of Laura’s orb. As generated by the Fireman, she is super-infused with corn—she is highly potent fuel. But Judy will not feed on good, healthy corn. Only black corn will do. Leland and BOB had to take care of that corruption. When the Fireman freezes the picture on the shot of the BOB orb emerging from Judy, it is not because he sees BOB as the central threat (though at this point in the series, the viewer is supposed to think so). It’s because BOB is unwittingly part of the plan to defeat Judy.

“There are some things that will change.”

Meanwhile, 25 years later, in the regular universe: the Fireman diverts Mr. C from Sarah’s house (Twin Peaks’ most negative location) to the sheriff’s station (Twin Peaks’ most positive location). Mr. C sought garmonbozia and so was drawn to Sarah Palmer, but he was being set up by Jeffries and Briggs all along. His plotline isn’t crucial to the Trap, which is why his defeat came so easily with the aid of a hastily-recruited English kid with a superpowered glove. He did some damage, but Cooper-as-Dougie was untouchable due to White Lodge management. Mr. C kept BOB fed with garmonbozia after Laura’s death, but that danger was fairly minimal compared to the apocalyptic threat posed by Judy, so that Mr. C didn’t even show up on Gordon and Albert’s radar until 2016, and Gordon is fairly indifferent when Mr. C escapes from prison. (Given Ray’s status as an informant and Gordon’s connections to Phillip Jeffries, it is easily possible Gordon was in on the escape plan.) Gordon is rather Machiavellian and callous when it comes to the suffering of others. He may have gone soft on Diane’s tulpa, but he’s not soft where it counts. The anger Diane’s tulpa felt toward Gordon and the FBI is real and justified. She’s being used by them.

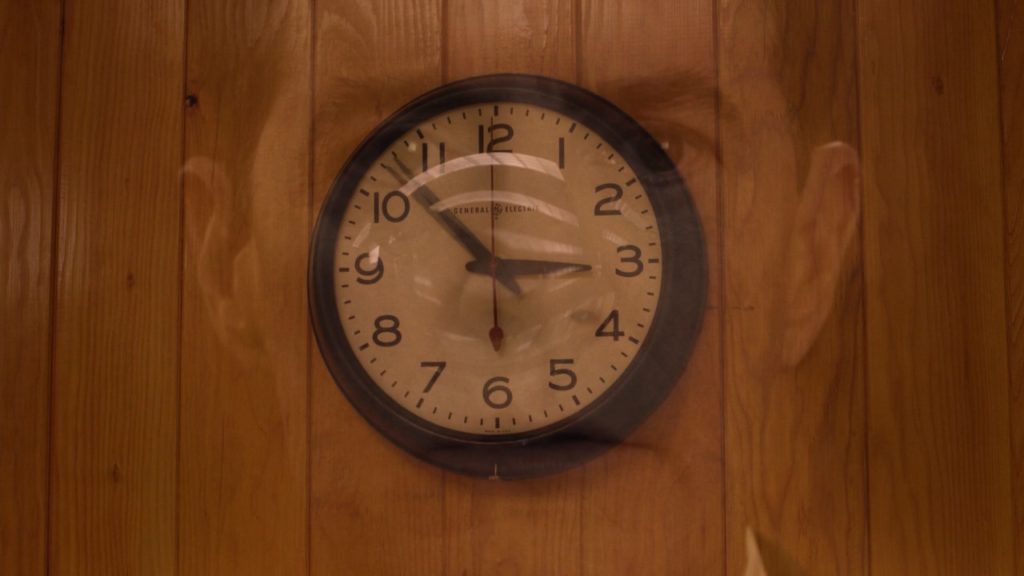

When the clock locks on 2:53, it signals the completion of this world’s story, which will soon become the “unofficial version.” As the Log Lady said, “The glow is dying…the circle is almost complete.” 2 + 5 + 3 = 10, “the number of completion.” Diane and Cooper, who have both traveled outside of this story, move on to the final act along with Gordon, who possesses some sort of special powers himself.

2:53 Sunday, October 2

In between leaving the sheriff’s station and going to the basement of the Great Northern, Cooper, Gordon, and Diane formulate the solution to a problem with the plan. (Gordon also gives Cooper a replacement FBI pin.) Part of the plan, which involves rescuing Laura from the past, is still fine. The problem is that after being deposited in the Cage in 1989, Laura makes poor bait, because once in the Cage, she forgets her childhood, and so Judy is not lured into the Cage. That task falls to Cooper and Diane. Cooper, having already made use of Laura in the Trap, is also going to sacrifice himself and Diane to it.

Cooper takes another trip through the Red Room, similar but different from the path he took in episode two. He has crossed over into the new “official version.” The doppelgangers are gone, because they were not created in this version. More subtly, Laura is missing from the initial “Is it future or is it past?” scene with MIKE. The camera focuses on the empty chair where Laura sat in the first iteration. When we do see Laura, after Cooper speaks to the Arm, it is in fact Cooper’s memory of the first trip. We don’t see Cooper sit down or stand up, and the whole scene is abbreviated. The Laura Red Room scene in episode 18 is a flashback prompted by the Arm, to remind Cooper of his mission. Laura herself is sealed off in the Cage, and has been for many years.

“You don’t know what it’s going to be like.”

Cooper exits via Glastonbury Grove and meets Diane in the official version. We do not hear them speaking of the plan, but we know they aren’t certain what they will find in the Cage, and that Diane is nervous, while Cooper is resolute but joyless. They drive a rickety 70s-vintage car because they do expect to find a world stuck in 1989 or even earlier, because they will be entering Laura’s dreamworld. They enter a mysterious, empty world, and arrive at a motel with 80s-era fixtures: a rotary phone, CRT television, and old-fashioned locks. They check in and have disturbing, passionless sex.

“Turn off the light.”

This is where a symmetry with episode 1 comes in. I take the Experiment to be either Judy or an avatar of Judy. Sam and Tracey appeared to draw the Experiment to them by having sex (sex is almost always bad in Lynch films), whereupon the Experiment brutally slaughtered them at the height of their fear. Diane and Cooper now reenact this summoning ritual in order to draw Judy into the Cage. They both know this is the plan; while they both care for and love each other, this act of sex is anything but an act of love. Both are joyless. Cooper is dispassionate throughout, but remains focused on Diane with an expression of restrained concern. Diane tries to be affectionate but collapses into terror and tears, covering Cooper’s face and staring up at the ceiling.

None of this is unexpected to them. This was the plan all along. The suffering that Diane (and to a lesser extent Cooper) endures is a product of her having sex with the man who raped her. She knows it is going to be a traumatic experience: she sees her double outside of the motel because she is already dissociating at the prospect of having to sleep with Cooper, even though he’s not that Cooper. Cooper tells her to turn out the light in the hopes of sparing her some of the trauma, but it’s an empty gesture. He is guilt-ridden with the sins of his doppelganger. Their trauma helps lure Judy, but it is also what keeps them alive. Sam and Tracey were killed because they weren’t generating enough garmonbozia, so the Experiment mauled them to death to feast on their terror. But like Laura, good garmonbozia generators are worth keeping alive, so Judy does not kill Diane and Cooper. She enters the Cage to the tune of the Platters’ “My Prayer,” which also heralded Judy’s arrival by way of frog-bug in episode 8, but she leaves Diane and Cooper alive—or at least Cooper.

The disturbing nature of Diane and Cooper’s sex stems, ultimately, from two people violating every instinct of humanity, compassion, and love they possess in pursuit of an abstract greater good. In particular it stems from Cooper using Diane—with her consent, admittedly—as a means to an end in a brutally inhumane fashion. Cooper rarely had to choose between duty and instinct prior to now; they always pointed him in the same direction. Now they are completely incompatible.

The unnerving, pervasive desolation of this Cage dreamworld is a product of its being shaped by (a) Laura’s own traumatic history, (b) Judy’s malevolent influence, and (c) Cooper and (to a lesser extent) Diane’s horror at the task they are undertaking. Nothing good will come of anything in the Cage dreamworld. Any beneficial effects will be to the other world, which is of little emotional comfort to the people now stuck in the Cage. But the oppressive desolation may only add to the combustibility of the Laura-Judy garmonbozia megabomb.

Richard and Linda

The dreamworld is remade overnight due to some combination of (a) Judy’s presence, (b) Cooper and Diane’s presence, and (c) the Cage being shut. The world outside updates itself to the present-day, including Cooper’s car. Andreas Schou points out that Cooper’s car turns into the identical model that Mr. C was driving in episode 3 during his 2:53 car crash, indicating the assertion of the darker side of Cooper’s personality as well as Judy’s increasing influence over the Cage.

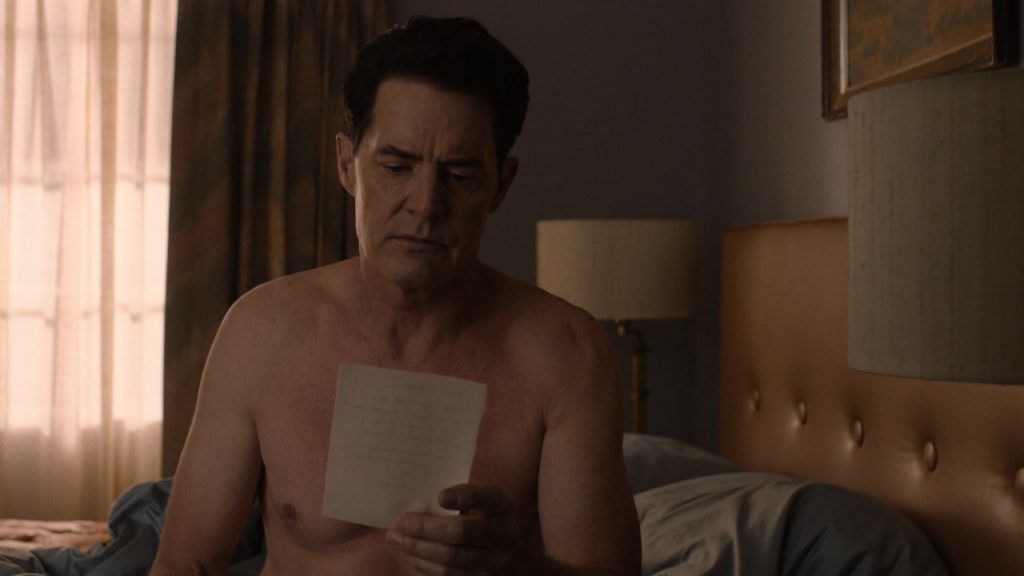

Cooper and Diane’s lives are rewritten as Richard and Linda’s. They are still the same souls, but their memories have been smeared and corrupted, as Carrie Page’s have been. Diane dissolves into Linda and leaves Richard, not knowing exactly what has going wrong but knowing she cannot face Richard anymore. (It is possible, on the other hand, that Judy simply consumed her, as Diane’s suffering was far greater than Cooper’s.) Cooper, who has a stronger will than Diane or Laura, hangs on to his past self, but when he reads the letter he knows he has sacrificed the person he cares for most in the world, Diane, to his plan. Diane may have been a willing accomplice, but the responsibility ultimately falls to him, and he is devastated. None of them were going to get out of the Cage alive, but Cooper is still devastated by Diane’s trauma and disappearance. He is very nearly broken by it, unable to enjoy coffee and closer to letting his dark side out than he ever has been before. The events of the first two seasons were child’s play next to this.

Once in the Cage, Judy takes up residence in a familiar place of pain: the Palmer residence in Twin Peaks. That’s unlikely to be the extent of her influence. She leaves white horse totems outside the diner and inside Carrie’s house. Judy may recognize Carrie as Laura, or at least as a rich supply of garmonbozia. Perhaps she leaves the #6 electrical pylon in place next to Carrie’s house to harvest garmonbozia, just as it harvested garmonbozia from the dead boy in episode 6. Perhaps it’s already siphoning a bit of garmonbozia as a result of the dead body in Carrie’s living room. Perhaps the events of Carrie’s last three days off work are a result of Judy’s malevolent influence newly suffusing the Cage.

Two familiar friends outside the new motel: the Evolution of the Arm and the Fireman (echoing the White Lodge’s standing lamps).

Exiting from a different motel than the one he checked into, Cooper remembers his task and joylessly goes about it, though he starts to lose track of himself. He focuses his mind on a single task: bring Laura to Sarah Palmer (who is Judy). He knows that Carrie Page needs to remember her horrible life as Laura in order for her to function as a bomb. She doesn’t. He still sees the Cage to be unreal, so he ignores the dead man in her living room, and is fairly callous with the people at the restaurant. They drive down very dark highways to Twin Peaks. Who knows how much of the rest of the world is even filled in? The world is not just disenchanted but empty: when they stop at the Valero gas station, there is no traffic at all until they start the car to drive again. The world only seems to exist immediately around them.

A totem of Judy’s presence

Some familiar things remain in the Cage. Twin Peaks will exist because it remains in Laura’s memory. They pass by the RR diner, which no longer has the RR2GO sign because neither Laura nor Cooper had any knowledge of it. Cooper thinks that Sarah Palmer will be living in the Palmer house and that Sarah will shock her into remembering. When they get to the Palmer house, he’s baffled that there is no record of the Palmers living there. Who else could be living there, if this world was shaped by Laura? The answer is Judy. The names Tremond and Chalfont stir vague memories in him, but the Cage is confusing him as well. He may well have forgotten about Diane by this point. Judy’s influence may be corrupting things as well. The Cage has been closed to make certain Judy cannot escape.

“I’m Special Agent Dale Cooper. What is your name?”

Cooper paces, confused, trying to hold on to his thoughts. “What year is this?” he asks, as one might ask one’s self in a dream. This stirs something in Laura, some knowledge of the Cage’s unreality, and it is enough so that Judy calls out to her in Sarah’s voice. At this point, Laura does remember, and she knows what she needs to do as well. It is possible that she has full knowledge of her role in the Trap. The collective weight of her past returns and she lets out a tremendous, violent shriek, discharging all her suffering within the confines of the Cage. The bomb explodes.

Discharge and detonation

The lights in the Palmer house overload and blow out. The electricity stops. The screen goes black and the scream dissolves into an echo and fades away. Judy is destroyed along with everything else in the Cage. The plan worked. “It” entered our house at the very beginning of episode 1 and exited at the very end of episode 18. The daughter’s trauma, caused by her father, destroys her mother.

Not coincidentally, Laura, Cooper, and Sarah Palmer are the three characters who have seen the white horse. The Log Lady said, “Woe to the ones who behold the pale horse.” All three are destroyed in the blast.

Power surge

Meanwhile: Leland, possessed by BOB, went on doing his thing after Laura disappeared off the face of the planet the night she was supposed to have died. Gordon remembers “the unofficial version” where Laura died, but he knows it was the right call and is not too bothered. Most of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me happened. Most everything else didn’t—which has implications for a lot of what happened in The Return. Mr. C and Richard Horne never existed in the “official version”…but neither did Douglas Jones (in any of his three incarnations) or Sonny Jim, the son who needed a sunny gym. Cooper sacrifices not only his own self and his true confidante Diane, but also his two children. The Oz-like fairy tale of Las Vegas and the noir nightmare of Buckhorn become the unofficial “dreams” of their respective Coopers.

The fairy tale

The fairy tale “wins” out over the noir in episode 17 (the previously untouchable Hutch and Chantal die easily as soon as they enter Dougie’s sphere of influence), but the resulting world “loses” out to the remade “official version” in which none of it happened. This hauntingly evokes Franz Kafka’s parable, “On Parables”:

A man once said: If you only followed the parables you yourselves would become parables and with that rid yourself of all your daily cares.

Another said: I bet that is also a parable.

The first said: You have won.

The second said: But unfortunately only in parable.

The first said: No, in reality: in parable you have lost.

In reality, Cooper wins—but he is no longer part of reality. He became a parable. He joins the ranks of Philip Jeffries and Chet Desmond, more legend than reality.

(This rewriting of history, however, may set up a Mobius-strip time loop in which the two versions oscillate, but I find that much less interesting than the horrible compromise Cooper has to make to make the Trap work, and what it does to our conception of his character, and particularly the impossibility of his character.)

And that leaves two speculations. First, the stone was Laura Palmer, and the two birds were Judy and BOB. (Cooper only hit one bird, since BOB was only wiped out in the “unofficial version.”) Second, Laura’s spirit (not necessarily Laura herself) whispered something like this to Cooper in episode 2: “You will use Diane and me to lure Judy into a trap where we will all die.” Or, “We are the dreamers who will die in our dream.” Or maybe something as simple as, “You will kill me.” In keeping with the symmetrical shape of The Return, Laura whispers to Cooper 80 minutes in, while Cooper “saves” Laura with 80 minutes remaining.

One last thought: anyone who could come up with such a cruel plan, no matter how beneficial, must have a very serious dark side. Cooper lost this dark side when his doppelganger was created in the Black Lodge. His soul was, if not annihilated, at least dis-integrated. Cooper’s shadow self was reintegrated with him the moment the doppelganger burned. Cooper needed his shadow self because of the darkness of his task. Dougie-level goodness alone is not sufficient to defeat Judy. I believe, in fact, that the controlled possession of his shadow self was necessary for him to open the curtain out of the Black Lodge that he was blocked from exiting in episode 2.

Integrated souls only.

With his doppelganger on the loose, he could not exit the Black Lodge via Glastonbury Grove, only through a bizarre White Lodge bypass mechanism operated by Naido. He bounced off the curtain. In episode 18, he easily opens it with a wave of his hand. With the doppelganger re-integrated into his self (and perhaps with a bit of his Dougie-ness lost), he is now a master of the Black Lodge and the White Lodge. (All references to doppelgangers are absent during his second trip through the Red Rooms.) But with his shadow self comes the heavy weight of guilt and sin that pervades Cooper throughout the final episode. He carries his doppelganger’s crimes with him, so that they too may cruelly serve the greater good.

“Meanwhile.”

UPDATE (9/8/2017): I appreciate all the great feedback below. I tried to restrict my thoughts to what I thought were the central puzzles around the ending, but here are a few other stabs at other pieces. I’m less certain on all of these, but I also think that their resolution is less critical to the coherence of The Return. For all its visceral impact, the finale felt incomplete to me in the absence of some greater explanation, and so I was driven to seek one. I hope there will continue to be other attempts to explain the whole story, all its twists and turns.

Audrey: Many have pointed out parallels between Audrey’s situation and the Cage’s dreamworld (which, in Charlie and the Arm’s terminology, would be Audrey and Laura/Carrie’s “stories”). One significant parallel is the retro furnishings: like the first iteration of the motel, Audrey’s house has a rotary phone and nothing I could see that’s more recent than the 1980s, if even then. This suggests she too is in some kind of isolated dreamworld, though probably not the Cage. Perhaps Mr. C stashed her there sometime after Richard grew up (Ben says Richard never had a father, but not that he never had a mother), or perhaps the trauma of raising Black Lodge baby Richard had enough of an effect to send her there. Audrey and Laura both become generic “little girls who live down the lane,” though Audrey struggles against this new story until she finally breaks through.

But when she wakes up, where is she? Lynch’s use of a totally white background is, as far as I know, unprecedented for him, which makes me hesitant to guess, but her clothes do make it look like she is in an institution. The “reality” of the Roadhouse is liminal; it’s the one location that seems to stand in between all the worlds of the show, so the Roadhouse may allow her to transition back to some other world. (The sound of electricity in the background does match up with other instances of cross-world travel.) Maybe she’s awakening from catatonia? I haven’t found enough clues to justify a particular interpretation of her awakening. The uniqueness of the all-white background may indicate that her fate is unknown or open-ended. (Update: Mark Frost’s Final Dossier states that she ended up in a private mental care facility.)

Mr. C: Mr. C asks Jeffries who Judy is, but he does know what Judy is—the entity of evil on the Ace of Spades. He wants Jeffries to tell him who Judy is now, and asks if Judy wants something from him. By this point he is suspicious of Jeffries (who tried to have him killed) and may be playing dumb as well. He may be wondering if Judy wants BOB from him, as BOB is her child, and it’s implied Mr. C would rather not give him up. Or maybe he is trying to return BOB to his mother in exchange for something, and he is inquiring to find out whether Judy is interested. Mr. C’s ultimate plans with Judy remain unclear to me—I suspect it involves the annihilation of the good Cooper so that he can live out his days with his Woodsmen entourage—but he does want to find her. But due to the combined efforts of Jeffries and the Fireman, he is diverted from being delivered to Judy at Sarah Palmer’s house and instead ends up at the sheriff’s station, where the forces of good are arrayed against him and easily defeat him.

Jay Rubenstein raises the intriguing possibility that Mr. C was the one to formulate the original Judy plan with Briggs, which he then took to Gordon after killing Briggs. The timing on this is plausible, though it requires Gordon not to have recognized anything wrong with Mr. C. In this event, the plan was flawed from the start since Mr. C surely had bad intentions, and it took the intervention of the Fireman, Briggs, Diane, and Cooper in order to set the plan aright while Gordon and Jeffries remained in the dark. If so, Mr. C’s phone call in episode 2 could indeed be from Jeffries, but a Jeffries who has finally figured out that Mr. C is not Cooper—hence Mr. C’s surprise and his attempts to ingratiate himself with Gordon while in Yankton prison.

MIKE: MIKE’s motivations were muddled even before The Return. The one constant is that he always opposes BOB, but in Fire Walk WIth Me, MIKE appears far less altruistic, fighting BOB because he wants garmonbozia rather than out of the goodness of his heart. In The Return, he seems far more benign and takes orders from Cooper, but this may also be out of necessity, self-interest, or a desire to preserve the status quo. But why did MIKE give Laura the ring? I think there is an answer that works within the scope of Fire Walk With Me, which is that the ring would take Laura (and her garmonbozia) away from BOB and bring her to the Black Lodge, where MIKE resides. MIKE was not in on any greater plan at that time, and from his perspective BOB was the biggest problem.

Had Laura not taken the ring, she would have been possessed by BOB, and perhaps she would have eventually served as a host for Judy (as Laura is highly fertile with corn, and thus a far better mother candidate than Sarah). Maybe this was the original plan: after Judy possessed Laura, she could be easily recalled to the White Lodge, contained, and detonated somewhere safely. Laura’s death solves the Black Lodge’s BOB problem, but by the time of The Return, Judy is a much bigger problem for everyone—from the perspective of the Black Lodge, she’s a garmonbozia robber baron. This is highly speculative, however, and I’m skeptical of attempts to reconcile Fire Walk With Me too closely with The Return, because MIKE’s apparent character changes so drastically.

Girl (1956): I agree with the common sentiment that if any character we’ve seen is the 1956 girl, it’s Sarah Palmer. The timing matches up, but some other corroborating evidence would be nice. (Update: Mark Frost’s Final Dossier confirms that it’s Sarah Palmer.) But what’s also interesting is why the girl is picked out by Judy’s frogbug. My sense is that she is chosen because of the combination of sexual excitement and shame she is feeling, and the link of those feelings to garmonbozia. The shame stems not only from allowing the boy to kiss her, but also because the boy is not white: both factors which would have caused anxiety in many a fair-skinned 1950s teenage girl.

Red: I have no idea what is up with Red. Sara Tomko and Filippo Malatesti suggest he may be Mrs. Chalfont/Tremond’s magician grandson. Perhaps his question about a singular hand (not hands) is his way of telling Richard to examine his spiritual finger on his left hand? Richard is a horrible human being, but he was doomed to be that way from conception. (Update: in light of the following comments on the diary, I now think the case for his being Tremond’s grandson is quite strong.)

“Have you ever studied your hand?”

Appendix: The Cage and the (Carrie) Page

“I leaned over and whispered the secret in his ear.”

After a good deal of reflection, I’m now convinced that Laura Palmer’s diary is considerably more central to The Return than it initially appears. I believe the diary is the Cage.

Consider the following:

- The focus on the missing pages of the diary, by the Log Lady herself no less.

- Hawk’s conspicuous statement that only three out of four missing pages are located, and that Leland surely hid them.

- The diary passed through the hands of Mrs. Tremond and her grandson, both strongly identified with Judy.

- The impossibly tangled chronology of the diary.

- The Tremond/Chalfont connection at the Palmer house in the final scene.

- Carrie Page’s surname.

There is no hint given as to the contents of the missing page. But I think we’ve already been given it. It’s the page Donna got from the “fake” Mrs. Tremond in the original series (ep 2.9):

February 22nd. Last night I had the strangest dream. I was in a red room with a small man dressed in red and an old man sitting in a chair. I tried to talk to him. I wanted to tell him who BOB is because I thought he could help me. But my words came out slow and odd. It was frustrating trying to talk. I got up and walked to the old man. Then I leaned over and whispered the secret in his ear. Somebody has to stop BOB. BOB’s only afraid of one man, he told me once. A man named Mike. I wonder if this was Mike in my dream. Even if it was only a dream, I hope he heard me. No one in the real world would believe me.

February 23. Tonight is the night that I die. I know I have to because it’s the only way to keep Bob away from me. The only way to tear him out from inside. I know he wants me. I can feel his fire. But if I die he can’t hurt me anymore.

This is the last page of the diary. Leland didn’t take it. Harold Smith ripped out this last page and sealed it in an envelope, while mutilating the rest of the diary. How it got into Mrs. Tremond’s mailbox is quite a mystery, since Harold was an agoraphobic shut-in. Mrs. Tremond sent Donna to Harold in the first place, so we can surmise that she played a large part in engineering that entire sequence of events, including Harold’s suicide, and I suspect Harold was in thrall to the Black Lodge to some great extent. As to why the page was passed on to Donna, I’m not certain: perhaps it was a trap for Cooper (in which case it worked).

Chateau Tremond

The time sequence in Fire Walk With Me goes something like this:

- Feb 16: Laura finds at least two pages missing (two loud tearing sounds), gives diary to Harold, saying BOB took them. “You made me write it all down. He doesn’t know about you.”

- Feb 17: Tremond/Chalfont gives Laura the red wallpaper painting that acts as gateway to Red Room. (Note: same wallpaper as in Dutchman staircase room in The Return.)

- Feb 17: Tremond/Chalfont’s grandson (dressed as Jumping Man) tells Laura that “man behind the mask” is looking for “the book with the pages torn out.”

- Feb 17: Laura has ring dream with Annie, writes page about Good Cooper being trapped in the Lodge.

- Feb 21: Laura has Red Room dream (ep 2.9)

- Feb 22: Laura writes final page above about Cooper Red Room dream (ep 2.9).

- Feb 23: Laura writes remainder of final page about how she’s going to die (ep 2.9).

- Feb 23: Leland kills Laura, with the torn pages in his possession. (Harold still has remainder of diary.)

Even within Fire Walk With Me, the chronology is so muddled as to be incoherent, requiring Leland to have torn out pages that Laura only wrote after giving the diary away because she found those same pages torn out. Tremond’s statement on its own is paradoxical: the man behind the mask (BOB) is looking for the book which he himself already found and tore the pages out of. I don’t think there is a resolution per se to this confusion. Rather, I just want to use it to point out that the diary is special and temporally abnormal, especially after it falls into the Black Lodge’s hands. This doesn’t mean there are multiple realities. There is only one official reality and only one Laura Palmer. It just means that the diary is closer to the Red Room and the Black Lodge than it is to “reality.”

But it’s that final page (and specifically the February 22 entry) which is most important, since it contains the central scene of Twin Peaks: Laura “Full of Secrets” Palmer whispering a secret to an older Cooper in the Red Room. Not only is it the first and only interaction Cooper and Laura ever properly have prior to the end of The Return, but it also describes the final image of The Return: the credits roll over the shot of the older Laura whispering to the older Cooper.

The Red Room is central enough to the entire show that a diary page describing it is serious business. And it is anachronistic and temporally stretched: is it future or is it past? When Mike asks that question, it’s to say, “Is this dream right now future or is it past?” Even after Cooper changes the past, that dream remains, except that Laura (and the doppelgangers) are no longer in the dream.

The Whole Sick Black Lodge Crew

(I have been tempted by the theory that the mysterious sound that the Fireman plays for Cooper, and which is heard immediately prior to Laura’s disappearance after Cooper “rescues” her in the past, is the sound of Laura unlocking her diary in Fire Walk With Me. Unfortunately, it’s not the secret diary, which has no lock. It’s her datebook where she stashes cocaine.)

After Cooper changes the past by “rescuing” Laura, the Black Lodge is in possession of the diary. Leland has three of the pages, but Judy could presumably recover these rather easily. That diary, as a chronicle of Laura’s trauma and abuse, is the most significant indicator remaining of Laura’s pain. It’s probably glowing with garmonbozia. Laura, however, is gone.

As for the fourth page, it was never removed, but bear in mind, the dream has changed. Regardless of causality, Laura is no longer in the Red Room dream in the new version, future or past. There’s no way she can write about it at any point in time. Leland says “Find Laura” because Laura is gone from the entire scope of the Red Room experience.

We saw her being removed. Laura’s first appearance in The Return, after she re-enacts the kiss and whisper with Cooper, ends with her being pulled up and somewhat to the right, as she screams. This is followed by a vision of Judy’s white horse, previously seen exclusively by Sarah Palmer. Laura and the white horse are only finally united in Odessa in the final episode. Now, this is my interpretation, but the jagged direction of Laura’s movement is not unlike a page being torn out of a book.

Laura being ripped from the Red Room.

Her scream, again, is identical to the one given when she disappears after being “rescued” by Dale, accompanied by the Fireman’s gramophone sound. So I propose that what Cooper does over the course of The Return, with the assistance of MIKE and the Fireman, is rip Laura Palmer from the story of Twin Peaks, and more specifically from the Red Room. Through unspecified White Lodge machinations, Laura then becomes Carrie Page, the missing “page” of this chronologically screwed-up diary. Disconnected temporally and causally from the conventional world, the diary becomes sufficiently isolated (sufficiently “secret,” if you will) to serve as the Cage. (Perhaps the diary, too, is pulled from “reality” along with Laura.) All that’s left is to lure Judy into it.

The final episode, like the diary, is temporally unmoored. Cooper and Diane serve as the catalyst to summon Judy and detonate the garmonbozia mega-bomb within the pocket world of the diary. As Carrie Page, Laura is the dreamer who lives inside the dream she wrote in her own diary. There were many dreamers over the course of the series, frequently sharing each other’s dreams: Dale Cooper, Phillip Jeffries, Gordon Cole, Audrey Horne, William Hastings, Bradley Mitchum, and others. But ultimately, the dreamer who matters the most is Laura, and her dreams and her diary possess the same nature. Laura is the one.