- Georg Simmel’s Philosophy of Money: An Introduction

- Georg Simmel’s Philosophy of Money: 1. Value and Money

- Georg Simmel’s Philosophy of Money: 2. The Value of Money as a Substance

- Georg Simmel’s Philosophy of Money: 3. Money in the Sequence of Purposes

- Georg Simmel’s Philosophy of Money: 4. Individual Freedom

- Georg Simmel’s Philosophy of Money: 5. The Money Equivalent of Personal Values

- Georg Simmel’s Philosophy of Money: 6. The Style of Life

To review: in the first two chapters, Simmel established money’s capacities to (a) make incommensurable systems of values commensurable, and (b) dissolve meaning through a process of universalizing abstraction. He reviews the Kantian analysis of the second chapter:

What one might term the tragedy of human concept formation lies in the fact that the higher concept, which through its breadth embraces a growing number of details, must count upon increasing loss of content. Money is the perfect practical counterpart of such a higher category, namely a form of being whose qualities are generality and lack of content; a form of being that endows these qualities with real power and whose relation to all the contrary qualities of the objects transacted and to their psychological constellations can be equally interpreted as service and as domination.

“Money in the Sequence of Purposes” concludes the first half and first part of Simmel’s Philosophy of Money, the “analytic part.” Simmel now turns to the teleological paradox of money. This paradox, in short, is this: by privileging a universal quantity over individual qualities, money becomes its own end. This is a paradox because money’s meaning lies sheerly in its lack of any particular end: it’s not good for anything in itself. Yet because the sum of money’s potential ends are always far greater than what may be gained from any one of them, it takes on a universal potentiality greater than any actual good, and becomes more valued in itself. It is a universal tool.

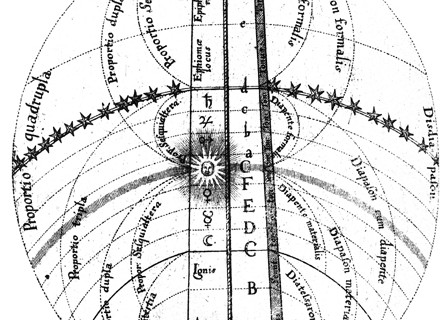

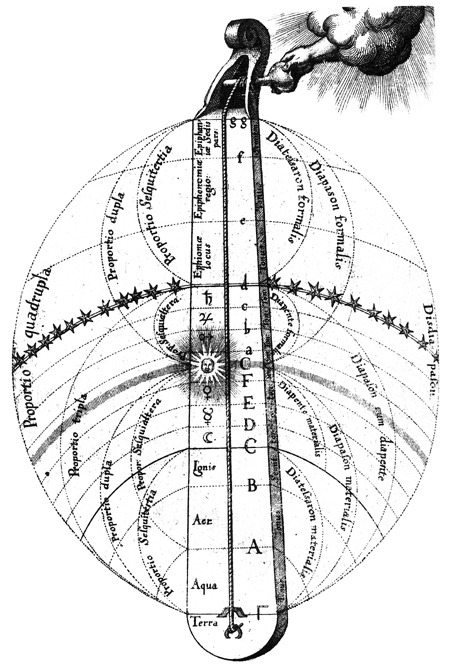

Love, which according to Plato is an intermediate stage between possessing and not-possessing, is in the inner subjective life what means are in the objective external world. For man, who is always striving, never satisfied, always becoming, love is the true human condition. Means, on the other hand, and their enhanced form, the tool, symbolize the human genus. The tool illustrates or incorporates the grandeur of the human will, and at the same time its limitations. The practical necessity to introduce a series of intermediate steps between ourselves and our ends has perhaps given rise to the concept of the past, and so has endowed man with his specific sense of life, of its extent and its limits, as a watershed between past and future. Money is the purest reification of means, a concrete instrument which is absolutely identical with its abstract concept; it is a pure instrument. The tremendous importance of money for understanding the basic motives of life lies in the fact that money embodies and sublimates the practical relation of man to the objects of his will, his power and his impotence; one might say, paradoxically, that man is an indirect being.

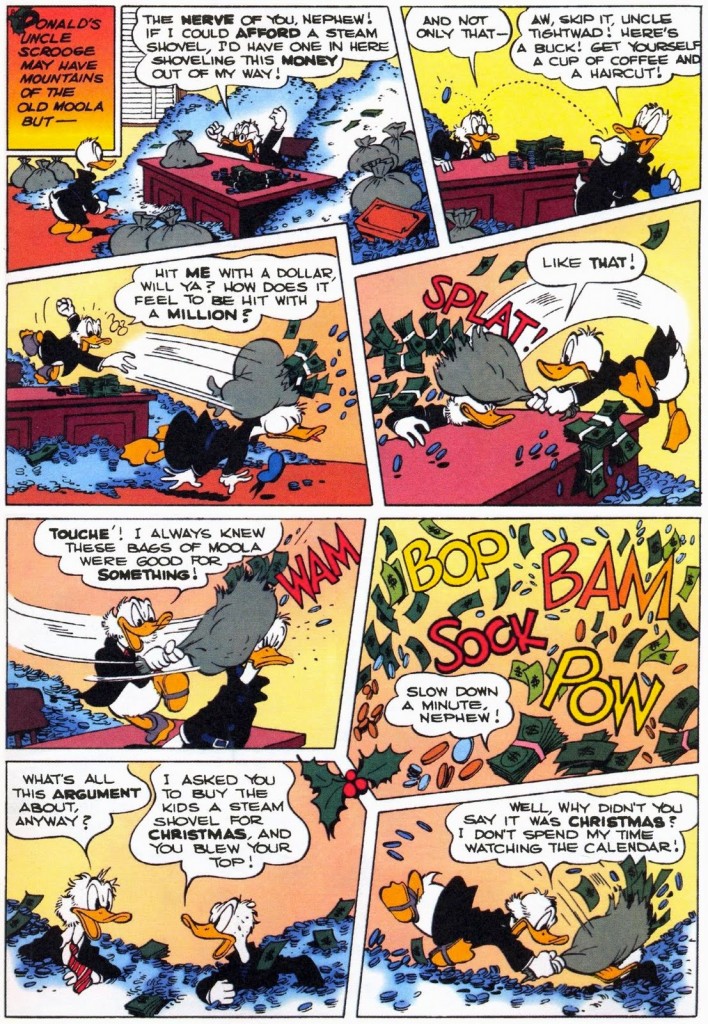

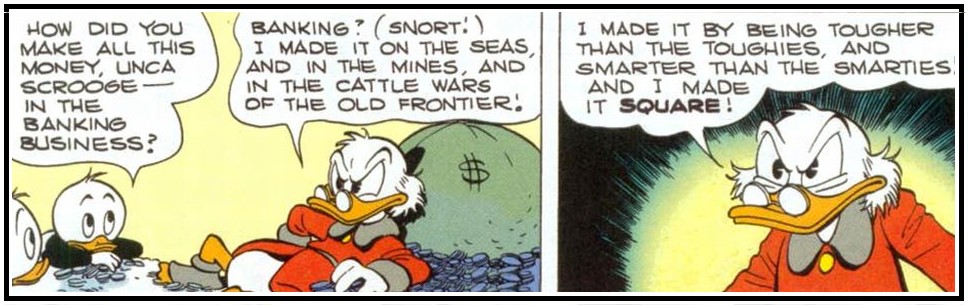

For those of you who’ve been waiting to see Uncle Scrooge show up, you can see a bit of this paradox in Carl Barks’ inconsistent treatment of how Scrooge feels about his money: sometimes he loves it for the pleasure its physical presence brings him, other times he loves it for the history behind the acquisition of the particular coins, while other times it is a mark of his superiority of having been “tougher than the toughies and smarter than the smarties”; regardless, however, Scrooge never really talks about what he can do with it (nor does he ever actually do that much about it besides swim in it and worry about it).

Simmel suggests that the rich attract our interest and worship as much for their vast potential of actions (“What would I do with that money?”) as for their particular lavish lifestyles:

This usurious interest upon wealth, these advantages that its possessor gains without being obliged to give anything in return, are bound up with the money form of value. For those phenomena obviously express or reflect that unlimited freedom of use which distinguishes money from all other values. This it is that creates the state of affairs in which a rich man has an influence not only by what he does but also by what he could do; a great fortune is encircled by innumerable possibilities of use, as though by an astral body, which extend far beyond the employment of the income from it on the benefits which the income brings to other people. The German language indicates this by the use of the word Vermögen, which means ‘to be able to do something’, for a great fortune.

Now, finally, Simmel brings Marx into the equation. The alienation of the worker from labor, Simmel argues, precisely parallels the divorce of money from concrete meaning and particular ends. This is not a consequence of capitalist exploitation per se, but a consequence of modern urban society itself. The result is tragic:

With increasing competition and increasing division of labour, the purposes of life become harder to attain; that is, they require an ever-increasing infrastructure of means. A larger proportion of civilized man remains forever enslaved, in every sense of the word, in the interest in technics. The conditions on which the realization of the ultimate object depends claim their attention, and they concentrate their strength on them, so that every real purpose completely disappears from consciousness. Indeed, they are often denied.

By removing Hegel from Marx, Simmel turns Marx’s vision of capitalist economy bleaker. There is no dialectical process at work here, just a dynamic, organic growth that increasingly distances individuals from a grasp of meaning, replacing particular linkages with the generic, abstract links of money. Consequently, an individual sees instead of concrete relations, a confusing mass of inadequate potential. In one of his most poetic moments, Simmel describes the sheer strain this puts on the individual consciousness and our efforts to live simultaneously in the moment and for the future:

We are supposed to treat life as if each of its moments were a final purpose; every moment is supposed to be taken to be so important as if life existed for its sake. At the same time, we are supposed to live as if none of its moments were final, as if our sense of value did not stop with any moment and each should be a transitional point and a means to higher and higher stages. This apparently contradictory double demand upon every moment of life, to be at the same time both final and yet not final, evolves from our innermost being in which the soul determines our relation to life—and finds, oddly enough, an almost ironical fulfilment in money, the entity most external to it, since it stands above all qualities and intensities of existing forms of the mind.

The result is at once to feel inextricably a part of a unified dynamo, yet without the perspective or the agency to grasp one’s particular place in it or establish it. For contrast, the Greeks’ (i.e., Athenians) sense of finite placement and the strict division of rights based on land-ownership gave them the bearing to reify a substance-centric philosophy.

Landed property, the relatively safe possession protected by law, was the only possession that could guarantee for the Greeks the continuity and unity of their awareness for life. In this respect, the Greeks were still Orientals, in that they conceived the continuity of life only if the fleetingness of time was supplemented by a solid and constant content. It is thus the adherence to the concept of substance that characterizes the whole of Greek philosophy. This does not at all characterize the reality of Greek life, but rather its failures, its longing and its salvation. It reflects the tremendous scope of the Greek mind in that it not only sought its ideals in the extension and completion of the given, as happened with lesser-spirited people, but further reflected this scope in their attempt to complete their passionately endangered reality—always disrupted by party strife—in another realm, in the secure bounds and quiet forms of their thoughts and creations. The modern view, in total contrast, views the unity and coherence of life in the interplay of forces and the law-like sequence of moments that vary their content to the utmost. The whole diversity and motion of our life does not dispose of the feeling of unity—at least not usually, and then only in cases where we ourselves perceive deviations or deficiencies; on the contrary, life is sustained by it and brought to fullest consciousness by it. This dynamic unity was foreign to the Greeks. The same basic trait that allowed their aesthetic ideals to culminate in their forms of architecture and plastic arts and that led their view of life to be one of a limited and finite cosmos and the rejection of infinity—this trait allowed them to recognize the continuity of existence only as something substantial, as resting upon, and realized in, landed property, whereas the modern view of life rests upon money whose nature is fluctuating and which presents the identity of essence in the greatest and most changing variety of equivalents.

Well, maybe–this probably says more about Simmel than the Greeks. The point is clear, though: we are comparatively unmoored even as we are more integrated. And as we work for money rather than particular goods, our goals become more unmoored because we conceive of our goals in aggregate, in terms of a particular income or particular buying power, before we conceive of ends in particular forms, because the achievement of those forms is presented in terms of monetary cost. When we do settle on a particular end, money reminds us that that end is hardly final, because we have selected it among all the other uses to which our money could have been put. Money reveals to us that the chain of “ends” never ends.

That the means become ends is justified by the fact that, in the last analysis, ends are only means. Out of the endless series of possible volitions, self-developing actions and satisfactions, we almost arbitrarily designate one moment as the ultimate end, for which everything preceding it is only a means; whereas an objective observer or later even we ourselves have to posit for the future the genuinely effective and valid purposes without their being secured against a similar fate. At this point of extreme tension between the relativity of our endeavours and the absoluteness of the idea of a final purpose, money again becomes significant and a previous suggestion is developed further. As the expression and equivalent of the value of things, and at the same time as a pure means and an indifferent transitional stage, money symbolizes the established fact that the values for which we strive and which we experience are ultimately revealed to be means and temporary entities.

Once again: money is pure teleological form without content. By being the ultimate in mere means it embodies the most general (and most empty) of ends. What this confusing relationship entails is, more or less, the collapse of the means/ends distinction by reducing everything to means.

Money is not content with being just another final purpose of life alongside wisdom and art, personal significance and strength, beauty and love; but in so far as money does adopt this position it gains the power to reduce the other purposes to the level of means.

The abstract character of money, its remoteness from any specific enjoyment in and for itself, supports an objective delight in money, in the awareness of a value that extends far beyond all individual and personal enjoyment of its benefits. If money is no longer a purpose, in the sense in which any other tool has a purpose in terms of its useful application, but is rather a final purpose to those greedy for money, then it is furthermore not even a final purpose in the sense of an enjoyment. Instead, for the miser, money is kept outside of this personal sphere which is taboo to him. To him, money is an object of timid respect. The miser loves money as one loves a highly admired person who makes us happy simply by his existence and by our knowing him and being with him, without our relation to him as an individual taking the form of concrete enjoyment. In so far as, from the outset, the miser consciously forgoes the use of money as a means towards any specific enjoyment, he places money at an unbridgeable distance from his subjectivity, a distance that he nevertheless constantly attempts to overcome through the awareness of his ownership.

All objects that we want to possess are expected to achieve something for us once we own them. The often tragic, often humorous incommensurability between wish and fulfilment is due to the inadequate anticipation of this achievement of which I have just spoken. But money is not expected to achieve anything for the greedy person over and above its mere ownership. We know more about money than about any other object because there is nothing to be known about money and so it cannot hide anything from us.It is a thing absolutely lacking in qualities and therefore cannot, as can even the most pitiful object, conceal within itself any surprises or disappointments. Whoever really and definitely only wants money is absolutely safe from such experiences. The general human weakness to rate what is longed for differently compared with what is attained reaches its apogee in greed for money because such greed only fulfils consciousness of purpose in an illusory and untenable fashion; on the other hand, this weakness is completely removed as soon as the will is really completely satisfied by the ownership of money. If we desire to arrange human destiny according to the scheme of relationship between the wish and its object, then we must concede that, in terms of the final point in the sequence of purposes, money is the most inadequate but also the most adequate object of our endeavours.

This passage is a fairly blatant echo of Hegel’s very famous lordship/bondage dialectic, except the bondsman is absent. Again, Simmel abandons Hegel for Kant. The problem is not one of intersubjectivity, but that of an individual consciousness, the miser, accumulating an object that is devoid of content, being satisfied with the thought that money cannot disappoint the miser’s expectations because money has no expectations to disappoint. All you can do is own it.

Revising Hegel further, Simmel then replaces the skeptic and the stoic with his own two opposed attitudes: the cynical and the blase. (Unlike Hegel, these are available to the miser as well as the missing bondsman.) The cynic devalues everything save for money in itself, while the blase individual simply becomes indifferent, paralleling the skeptic and the stoic respectively.

The nurseries of cynicism are therefore those places with huge turnovers, exemplified in stock exchange dealings, where money is available in huge quantities and changes owners easily. The more money becomes the sole centre of interest, the more one discovers that honour and conviction, talent and virtue, beauty and salvation of the soul, are exchanged against money and so the more a mocking and frivolous attitude will develop in relation to these higher values that are for sale for the same kind of value as groceries, and that also command a ‘market price’. The concept of a market price for values which, according to their nature, reject any evaluation except in terms of their own categories and ideals is the perfect objectification of what cynicism presents in the form of a subjective reflex.

Whereas the cynic is still moved to a reaction by the sphere of value, even if in the perverse sense that he considers the downward movement of values part of the attraction of life, the blasé person—although the concept of such a person is rarely fully realized—has completely lost the feeling for value differences. He experiences all things as being of an equally dull and grey hue, as not worth getting excited about, particularly where the will is concerned. The decisive moment here— and one that is denied to the blasé—is not the devaluation of things as such, but indifference to their specific qualities from which the whole liveliness of feeling and volition originates. Whoever has become possessed by the fact that the same amount of money can procure all the possibilities that life has to offer must also become blasé.

Simmel now turns to the subject of money’s quantification. The very notion of quantity implies that there can be more than one of something, and so money is treated not by individual units (which would be meaningless) but in the aggregate, and its power is purely determined through the comparison of aggregates rather than any outside measure. This sort of quantified object is totally without form:

As a purely arithmetical addition of value units, money can be characterized as absolutely formless. Formlessness and a purely quantitative character are one and the same. To the extent that things are considered only in terms of their quantity, their form is disregarded. This is most evident if they are weighed. Therefore, money as such is the most terrible destroyer of form.

If the object makes room for value elements other than form, then the number of times the object is created becomes important. This is also the basis of the deepest connection between Nietzsche’s ethical value theory and his aesthetic frame of mind. According to Nietzsche, the quality of a society is determined by the height of the values achieved in it no matter how isolated they may be; the quality of a society does not depend on the extent to which laudable qualities have spread. In the same way, the quality of an artistic period is not the result of the height and quantity of good average achievements but only of the height of the very best achievement. Thus the utilitarian, who is interested solely in the tangible results of action, is inclined towards socialism with its emphasis on the masses and on spreading desirable living conditions, whereas the idealistic moralist, to whom the more or less aesthetically expressible form of action is crucial, is usually an individualist, or at least, like Kant, someone who emphasizes the autonomy of the individual above all else. The same is true in the realm of subjective happiness. We often feel that the highest culmination of joie de vivre, which signifies for the individual his perfect self-realization in the material of existence, need not be repeated. To have experienced this once gives a value to life that would not, as a rule, be enhanced by its repetition. Such moments in which life has been brought to a point of unique self-fulfilment, and has completely subjected the resistance of matter—in the broadest sense—to our feelings and our will, spread an atmosphere that one might call a counterpart to timelessness, to species aeternitatis—a transcendence of number and of time.

Now, Simmel already made the case earlier for money’s formlessness based on its ability to assimilate and reconcile disparate value systems. Here he seems to be saying that commensurability and quantification are two sides of the same coin. The reconciliation of those value systems requires that some regularity of exchange be possible between them, and the only system for setting such rates is one that lacks any particular form–that is, numerical quantity. Contrariwise, the quantification of goods across multiple people, as a utilitarian would have it, obviously requires commensurability, which has often proven to be the utilitarian’s albatross. Simmel’s implication is that whether or not the utilitarian admits it, utilitarian philosophy effectively monetizes the good. There is no way to calculate maximum good or determine its distribution without emptying it of content.

This is all seeming very grim, but Simmel admits to some positive effects. The individual gains greater freedom to select which value systems to inhabit and exchange into. If you can determine a meaningful purpose for yourself, however arbitrarily, modernity gives you greater flexibility in pursuing it. Hence the paradox of the increase of individualism even as the individual is bound more tightly into a larger social system.

The contents of life—as they become more and more expressible in money which is absolutely continuous, rhythmical and indifferent to any distinctive form—are, at it were, split up into so many small parts; their rounded totalities are so shattered that any arbitrary synthesis and formation of them is possible. It is this process that provides the material for modern individualism and the abundance of its products. The personality clearly creates new unities of life with this basically unformed material and obviously operates with greater independence and variability compared with what was formerly done in close solidarity with material unities.

While the utilitarian or the socialist may empty things of aesthetic and moral content, such quantification nonetheless allows for more equality, since equality can now be calculated. Equality is not a notion that shows up all too often in the global history of thought, and when it does it’s usually restricted to conveniently ineffable things like souls. Money is what makes equality possible, by allowing for any particular imbalance to be compensated for. Likewise, we see the potential leveling of social inequality and elitism, since no one set of values necessarily has a lock on ultimate meaning, but all are subject to the empty arbiter of monetary value. Particular values are taken apart and reconstituted in the most general and distributed way possible, which in turn supports a democratic sentiment.

The same viewpoint can be observed in the historical sciences: language, the arts, institutions and cultural products of any kind are interpreted as the result of innumerable minimal contributions; the miracle of their origin is traced not to the quality of heroic individual personalities but to the quantity of the converging and condensed activities of a whole historical group. The small daily events of the intellectual, cultural and political life, whose sum total determines the overall picture of the historical scene, rather than the specific individual acts of the leaders, have now become the object of historical research. Where any prominence and qualitative incomparability of an individual still prevails, this is interpreted as an unusually lucky inheritance, that is as an event that includes and expresses a large quantity of accumulated energies and achievements of the human species. Indeed, even within a wholly individualistic ethic this democratic tendency is powerful and is elevated to a world view, while at the same time the inner nature of the soul is deprecated. This corresponds to the belief that the highest values are embedded in everyday existence and in each of its moments, but not in a heroic attitude or in catastrophes or outstanding deeds and experiences, which always have something arbitrary and superficial about them. We may all experience great passions and unheard-of flights of fancy, yet their final value depends on what they mean for those quiet, nameless and equable hours when alone the real and total self lives. Finally, despite all appearances to the contrary and all justified criticism, modern times as a whole are characterized throughout by a trend towards empiricism and hence display their innermost relationship to modern democracy in terms of form and sentiment. Empiricism replaces the single visionary or rational idea with the highest possible number of observations; it substitutes their qualitative character by the quantity of assembled individual cases. Psychological sensualism, which considers the most sublime and abstract forms and faculties of our reasons to be the mere accumulation and intensification of the most ordinary sensual elements, corresponds to this methodological intention.

Again: this is not just capitalism, this is modernity. The socialist or communist who promises a return to integrated meaning once exploitation and/or money is abolished is simply wrong unless they are also preaching a Luddite return to primitive society. The very thing that fuels modern society is the same thing that strips it of all particularized teleological meaning, and sets us toward seeing the world in an increasingly instrumental, quantified fashion.

Only metaphysics can construct entities completely lacking in quality, which perform the play of the world according to purely arithmetical relations. In the empirical world, however, only money is free from any quality and exclusively determined by quantity. Since we are unable to grasp pure being as pure energy in order to trace the particularity of the phenomena from the quantitative modifications of being or energy, and since we always have some kind of relationship—even though not always exactly the same one—with all specific things, their elements and origins, money is completely cut off from the corresponding relationships that concern it. Pure economic value has been embodied in a substance whose quantitative conditions bring about all kinds of peculiar formations without being able to bring into being anything other than its quantity. Thus, one of the major tendencies of life— the reduction of quality to quantity—achieves its highest and uniquely perfect representation in money.