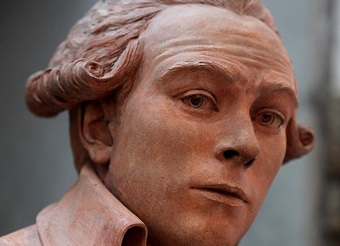

Robespierre in better times (1791)

I remember many years ago being very surprised to find out that there were people who esteemed Robespierre. Not only esteemed him but idealized him. I’d been raised on the standard account by which Robespierre was a bad guy, not on the order of Stalin or Mao, but indisputably an unsympathetic villain. Seeing him defended was about as surprising as if I’d found out there were fans of Louis XVI or Richard Nixon (little did I know…).

I think Alexander Cockburn’s memoirs were the first place I encountered a positive mention of Robespierre. Eric Hobsbawm’s histories are sympathetic but far more tentative on the matter. But Cockburn had busts of Robespierre and Robespierre’s younger-and-badder lieutenant Saint-Just in his house, and proudly identified with the man who, at least in his mind, was an absolute patriot of the French Revolution and its ideals, executions and all.

I was later surprised again when I discovered that Robespierre-fandom had once been mainstream in the fairly Marxist French historical school in the first half of the 20th century, particularly the giants Albert Mathiez and George Lefebvre. Mathiez especially saluted Robespierre as an unalloyed hero.

The wheel has turned quite a bit since that time, since a lot more people today have read Simon Schama arguing that the whole revolution was rotten from the start (in his bestselling Citizens) than have even heard of Mathiez. Schama will never convince me, since I see very little to his argument that the Old Regime was coming around and would have treated the 99% better had they just been a little bit more patient, but the horrible bloody Revolution was doomed to violence from the start. Schama is tendentious and, more or less, wrong. And if you’re going to be biased, shouldn’t you at least be biased on the side of those who had it rotten, rather than those who lived in luxury while 99.9% of the country worked under them?

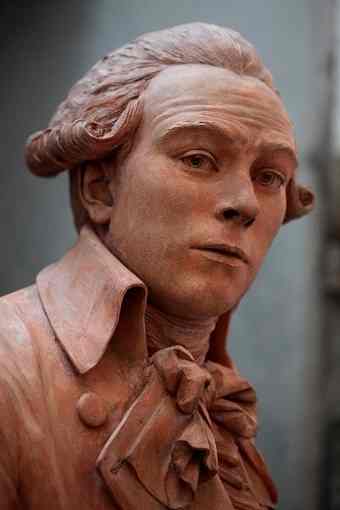

Georges Danton on a good day.

But on the other hand, I remain pretty unsympathetic to Robespierre, even though I find him fascinating as a human being. People tend to oppose the gregarious Danton and the hyperserious Robespierre, but I never much cared for Danton either, who comes off as a charismatic, though well-meaning, buffoon. I suspect I would have found Danton more annoying (and more corruptible) than Robespierre, but Robespierre was far more dangerous. I agree that “Robespierre the Incorruptible” was indeed incorruptible…but I also think that incorruptible people can be pretty scary. Robespierre had some glaring but not appalling personality flaws, like a puritanical obsession with purgative morality and a total lack of humor and self-awareness. These personality flaws were only going to become a problem if circumstances brought out the worst in him. Boy, did circumstances bring out the worst in him.

R. R. Palmer’s Twelve Who Ruled is an extremely well-written chronicle of the dictatorship of the Committee of Public Safety in 1793-94, as they tried to keep post-Revolutionary France from disintegrating through increasingly draconian methods, eventually resulting in the Terror. Eventually the twelve of the committee succumbed to infighting and. In Palmer’s account, Robespierre and his two closest allies Saint-Just and Couthon were squeezed on both sides when the more moderate technocrats (Carnot, Lindet, Prieur) and the revolutionary ultra-radicals (Billaud, Collot, and Bertrand Barere) abandoned them, which is how Robespierre and Saint-Just got the guillotine while the bloodthirsty Billaud and Collot survived. Unlike the high-minded Robespierre, Billaud and Collot come off as brutally proto-Leninist, while Barere’s mixture of idealism and opportunism defies easy explanation.

Cockburn endorsed Palmer’s book, which is somewhat surprising as Robespierre comes off rather badly. While Robespierre never appears as a murderous maniac, it’s actually more disturbing that a fundamentally nonviolent person would end up consenting to an regime of oppression, censorship, persecution, and executions. The source of Robespierre’s problems wasn’t paranoia either. Paranoia was in the air at the time, with very good reason. I don’t know that Robespierre was any more paranoid than anyone else in his circle, but the collective fear that everything was going to hell exacerbated Robespierre’s pre-existing tendencies to go overboard in his Manicheistic assessments of others. The originating flaw, as Palmer puts it:

Robespierre had the fault of a self-righteous and introverted man. Disagreement with himself he regarded simply as error, and in the face of it he would either withdraw into his own thoughts, or cast doubt on the motives behind the other man’s opinion. He was quick to charge others with the selfish interests of which he felt himself to be free. A concerted action in which he did not share seemed to him to be an intrigue. He had the virtues and the faults of an inquisitor. A lover of mankind, he could not enter with sympathy into the minds of his own neighbors.

Drawing on the equally unyielding Rousseau, who has since served as the founding text for much anti-liberal thought on both left and right, Robespierre smashed the public and private spheres together with a firm equation of Law = Morality = Justice = Goodness, seeing himself as the best arbiter of what fell inside their lines and what most certainly didn’t. The homogeneous totality of Rousseau’s General Will combined very badly the paranoia of the times, since opposing factions could not be loyal but had to be virulent and disagreement quickly turned into treason. Conciliation was therefore defeat. Again, Rousseau’s absolutist philosophy, unlike the far more practical, non-absolutist mainstream of the French Enlightenment, is distinctly unhelpful in such a situation:

Nor were the ideas to be gleaned from Rousseau more suited to encourage conciliation. In the philosophy of the Social Contract the “people” or “nation” is a moral abstraction. It is by nature good; its will is law. It is a solid indivisible thing. That the people might differ among themselves was a thought that Rousseau passed over rather hurriedly. Believers in the Social Contract thus viewed political circumstances in a highly simplified way. All struggles were between the people and something not the people, between the nation and something anti-national and alien. On the one hand was the public interest, self-evident, beyond questioning by an upright man; on the other hand were private interests, selfish, sinister and illegitimate. The followers of Rousseau were in no doubt which side they were on. It is not surprising that they would not only not compromise with conservative interests, but would not even tolerate free discussion among themselves, or have any confidence, when they disagreed, in each others’ motives. Robespierre in the first weeks of the Revolution was already, in his own words, “unmasking the enemies of the country.”

Robespierre stoked such fanaticism in others, which created a nasty feedback loop of encouraging further paranoia and purity, in a story that’s repeated itself many times before and since. (Look at how the Tea Party treats anyone with anything good to say about the Affordable Care Act or Obama, for example.) Character counted more for results, particularly when the judge was Robespierre’s de facto protege Saint-Just:

Saint-Just was a political puritan. He could not willingly work with men of whom he morally disapproved. He judged men more by their motives than by the contributions they might make to a common achievement. He feared that the good cause would be tarnished if dubious characters were allowed to promote it. This was not practical politics.

Saint-Just’s ideas were Robespierre’s ideas sharpened, simplified, exaggerated, schematized and turned into aphorisms. Robespierre had in him a broad streak of average human befuddlement, even mediocrity; Saint-Just was a specialized machine of revolutionary precision. Robespierre denied that Sparta was his model; Saint-Just harped continually on the ancients. Robespierre was self-righteous, Saint-Just more so: “God, protector of innocence and virtue, since you have led me among evil men it is surely to unmask them!” To Robespierre the straight and narrow way was plain enough; to Saint-Just it was terrifyingly obvious: “I think I may say that most political errors come from regarding legislation as a difficult science.” Or more laconically: “Long laws are public calamities.”

Demonizing opposing factions is one thing, but demonizing the People is a real problem, since Robespierre depended on the identity of his will with that of the People. This leaves open the question of what to do when The People do not agree with what you have decided. Robespierre was a great student of the idea of false consciousness before the term had even been coined. Ordinary people, alas, were suckers:

It is reassuring to be told that public opinion was the sole judge of what was in conformity with the law, but Robespierre claimed in the case of Avignon that, since all peoples aspired to be free, any Avignonnais who had not voted for incorporation into France ‘must be deemed oppressed’. Avignon was a local example of a more general problem. The goodness, patience and generosity of the mass of ordinary people meant that they were an easy prey to self-serving hypocrites. It was therefore the duty of the Assembly to ‘raise our fellow citizens’ souls . . . to the level of ideas and feelings required by this great and superb revolution’, Robespierre maintained in an undelivered speech of September 1789.

Robespierre’s problems were the product of what he believed to be his unique grasp of the political situation. The mass of the population meant well but, ‘aussi leger que genereux’, it was continually misled by ‘cowardly libellers’. On 3 March, he suggested sending the latter before the Revolutionary Tribunal, but that was merely striking at the symptoms. ‘Public feeling has lagged behind the Revolution . . . the people still lacks political sense.’ ‘Our enemies have public opinion in their hands.’ There had been sound political reasons for not submitting the fate of the king to a referendum, which would have made the division within the country explosively obvious, but that was not why Robespierre had opposed it. He asserted that ‘simple folk’ would be misled by ‘intriguers’ and that working people would not spare the time to attend the meetings of the primary assemblies. This was an argument, of course, that applied to all forms of democratic election. When, on 13 April, Gensonne’ proposed referring the Girondin-Montagnard quarrel to the electorate, Robespierre denounced such proposals as ‘blasphemies against liberty’.

Norman Hampson, “Robespierre and the Terror”

So Robespierre, unsurprisingly, had much less sympathy for trade unionism and civil protest once he had assumed dictatorial powers. While Hampson sees this as an outgrowth of his purism, Palmer sees it as an inevitable consequence of being in power:

The Committee, in short, was on the side of production, as most effective governments of whatever social philosophy apparently are. The labor policies of the revolutionary Republic and of the early industrial capitalists had much in common. The Committee punished strikes severely, and regarded agitators among the workmen as criminals at common law.

Nonetheless, Robespierre did want to bring the people along with him, and his rhetoric–and the rhetoric of the revolutionary government which he controlled–became focused on communal unity.

Privation can be met either by acceptance, which leads to Spartanism, or by discontent, which, when exploited for political aims, may lead to revolt. The Committee of Public Safety became increasingly Spartan, lauding the virtues of discipline and sacrifice. The reason was not simply that it was the government in office. “Virtue” was a favorite idea among the more honest Revolutionists; it meant a patriotism blended with a good deal of the old-fashioned morality of unselfishness. Of this quality Robespierre was the almost official spokesman; it was he who had put Virtue in the Revolutionary Calendar.

In the absence of 20th century mechanisms of control, central planning simply came off as inept. Again, much of the failings originated from Robespierre projecting on to The People an idealized vision out of touch with reality.

Saint-Just, like most other middle-class leaders of the Revolution, had almost no real knowledge of the problems of working-class people. He saw an undifferentiated mass of indigent patriots to whom it would be both humane and expedient to give land. He failed to distinguish between those who could use land and those who could not, between able-bodied landless agricultural laborers and the rest of the needy, the small artisans and city wage-earners, the not-quite-landless peasants, the old, the widowed, the orphaned, the crippled.

Increasingly frustrated and impatient, Robespierre charted out a plan to bring the entire populace into the realm of the True and the Good. This is his speech of February 5, 1794, which Palmer calls a milestone. It is pretty damn scary reading, from a man who was evidently unfamiliar with the maxim of “Underpromise and overdeliver.”

Too long, Robespierre began, have we acted in difficult circumstances only from a general concern for public good. We need “an exact theory and precise rules of conduct.”

“It is time to mark clearly the aim of the Revolution.

“We wish an order of things where all low and cruel passions are enchained by the laws, all beneficent and generous feelings awakened; where ambition is the desire to deserve glory and to be useful to one’s country; where distinctions arise only from equality itself; where the citizen is subject to the magistrate, the magistrate to the people, the people to justice; where the country secures the welfare of each individual, and each individual proudly enjoys the prosperity and glory of his country; where all minds are enlarged by the constant interchange of republican sentiments and by the need of earning the respect of a great people; where industry is an adornment to the liberty that ennobles it, and commerce the source of public wealth, not simply of monstrous riches for a few families.

“We wish to substitute in our country morality for egotism, probity for a mere sense of honor, principle for habit, duty for etiquette, the empire of reason for the tyranny of custom, contempt for vice for contempt for misfortune, pride for insolence, large-mindedness for vanity, the love of glory for the love of money, good men for good company, merit for intrigue, talent for conceit, truth for show, the charm of happiness for the tedium of pleasure, the grandeur of man for the triviality of grand society, a people magnanimous, powerful and happy for a people lovable, frivolous and wretched—that is to say, all the virtues and miracles of the Republic for all the vices and puerilities of the monarchy.

“We wish in a word to fulfil the course of nature, to accomplish the destiny of mankind, to make good the promises of philosophy, to absolve Providence from the long reign of tyranny and crime. May France, illustrious formerly among peoples of slaves, eclipse the glory of all free peoples that have existed, become the model to the nations, the terror of oppressors, the consolation of the oppressed, the ornament of the universe; and in sealing our work with our blood may we ourselves see at least the dawn of universal felicity gleam before us! That is our ambition. That is our aim.”

Maximilien could hardly have made it more clear. Nor could he have shown himself better as a child of the Enlightenment. He wanted a state founded upon morality, and by morality he meant not a sentimental goodheartedness, but the sum total of the qualities which he listed. His program was doubtless utopian; he expected a sudden regeneration of mankind, a complete transformation, seeing in the past no index, except negatively, to the future.”

Robespierre was eagerly coercive in bringing about this change. Again, his Incorruptibility went hand in hand with his self-determined Infallibility. These traits culminated in a very ham-fisted attempt at a deistic public religion, the Cult of the Supreme Being, described best by Norman Hampson:

Without consulting his colleagues on the Committee, Robespierre now persuaded the docile Assembly to adopt the cult of the Supreme Being, which marked a new stage in his identification of republicanism with morality. Since ‘the sole foundation of civil society is morality’, the prime objective of the enemy was ‘to corrupt public morals’. Crime was now equated with sin and vice versa, which meant that the scope for repression was virtually unlimited. Robespierre’s attempt to implement the penultimate chapter of the Social Contract was accompanied by a tribute to Rousseau whose ‘profound loathing of vice’ had earned him ‘hatred and persecution by his rivals and his false friends’. The parallel was too obvious to need elaborating.

Norman Hampson, “Robespierre and the Terror”

And with Robespierre being clearly out of touch at this point, trapped more between his ideals and reality than between the people and the government, it’s not surprising that he was unable to defend himself when the Committee broke ranks and turned against him. His defense of himself was a disaster, as Palmer recounts, ensuring that he would be scapegoated for all the Revolution’s excesses in the years immediately following and for many years beyond:

This address, the last Robespierre ever made, was eloquent, profoundly sincere, predominantly truthful. It painted a picture of dissension and intrigue that honeycombed the state. It described the means by which its author was made to seem individually responsible for the worst features of the Terror. It predicted that if the Revolutionary Government should fail a military dictatorship would follow, and France be plunged into a century of political unrest. But the speech was tactically a gigantic blunder. If it expressed Maximilien’s best qualities it unloosed all his worst; and it confirmed the most deadly fears of those who heard it.

Robespierre made his appeal supremely personal. Individualizing himself, he sounded like what the eighteenth century conceived a dictator to be. He gave the impression that no one was his friend, that no one could be trusted; that virtue, the people, the fatherland and the Convention, considered abstractly, were on his side, but that he obtained only calumny, persecution and martyrdom from the actual persons with whom he worked. He threatened right and left, indulgents and exaggerated terrorists, as in the past; but when asked point blank to name the men he accused, he evaded the question.

The immense irony was that Robespierre’s purism made it trivially easy to associate him with any ideological excesses. The ultra-revolutionary radicals who’d teamed up with the moderates to depose Robespierre soon realized that the word of the day was now pragmatism and compromise–and soon enough, weakness, paving the way for Napoleon. In death, Robespierre was now a pariah and dumping ground for all dissatisfactions, the convenient scapegoat for whatever had been going wrong that anyone didn’t like.

But in fact, to the consternation of extremists, 9 Thermidor fundamentally altered the Revolution. The extremists overthrew Robespierre by combining with moderates. They discredited Robespierre by blaming him for the violence of the Terror…To preach terrorism after Thermidor was to expose oneself to suspicions of Robespierrism, suspicions which above all others had to be avoided. Terrorists of the Year Two identified the Terror with one man, that they might themselves, by appearing peaceable and humane, win the confidence of the moderates. Barère revealed what was going on, writing in self-defense when he was himself accused: “Is his grave not wide enough for us to empty into it all our hatreds?” This was precisely what happened. The living sought a new harmony by agreeing to denounce the dead. And Maximilien Robespierre, who in life could not have stopped the Terror, contributed to its end in his death, by becoming a memory to be execrated and vilified, his grave a dumping ground for others’ hatreds.

Robespierre’s insistence on the incommensurability of virtue, the necessity of the Good in politics, his inability to compromise, his collapse of the personal and the political, his embrace of false consciousness as the condition of most of the public: these all extend the accusation of banausia as I described in Leftism and the Banausic Thinker. Not as ruthless or as cynical as Lenin, Robespierre depicts the revolutionary mindset in a purer form–one that some neo-Jacobins find very attractive. But I do think that like Robespierre and Saint-Just, you have to be drawn to integrity and idealism for its own sake, because it’s not clear from the facts themselves that Robespierre’s particular vision worked out any better than that of more practical politicians, particularly those of the early years of the Assembly, and they certainly resulted in more authorized bloodshed.

On the other hand, I notice a distinct retreat from Robespierre’s rhetoric in his supposed successors, less of a willingness to put forth the sheer gleaming vision that came to Robespierre so naturally. I can understand this retreat as the result of two factors:

- Historical lessons that have shown the gleaming vision to be further off than Robespierre believed.

- Reluctance to make sweeping accusations of false consciousness toward the populace, as Robespierre did.

Those positive visions can be a little scary. But The Gleaming Vision and False Consciousness are two of the most crucial tools in the Revolutionary’s toolbox. I think that the tepid nature of much current Leftist writing (when it isn’t just disappearing entirely into theory) owes to the lack of a forceful (coercively so) positive future vision, and the complementary near-myopic focus on critique. Radical critique has no fangs in the absence of a vividly better alternative. When Obama was putting forth fairly empty rhetoric of solidarity in 2008, most of what I heard as a concrete alternative, even from Leftist sources, was pretty straightforwardly Liberal/Progressive or Social Democratic. I didn’t really have a problem with that, but that is a problem for the radical left.

Without a Gleaming Vision, and the accusations of False Consciousness to level at those who reject the Gleaming Vision, critique only serves the purpose of establishing internal purity tests, one-upping dialogic opponents, and getting tenure or magazine posts. Allusions to Gleaming Visions remain steadfastly vague, whether you are reading Slavoj Zizek, Naomi Klein, Silvia Federici, or Antonio Negri. While they are hectoring in their criticism of capitalism’s blatant faults, they are fuzzy on the details of its successor–and thus the need for revolution rather than reform is not clear. Thomas Piketty’s surprisingly modest solutions in Capital in the 21st Century—a global wealth tax, but that’s about it–drastically separate him from the radical crowd. In The Nation, Timothy Shenk half-heartedly carps about Piketty’s incrementalism while making only the fuzziest motions at “a much richer set of possibilities” and “a more promising alternative” for the future. He doesn’t bother to say what they might be. That won’t cut it.

Besides, Shenk, I mention Negri in particular because the books he wrote with Michael Hardt (Empire, Multitude, Commonwealth) seem to have faded so quickly, the last one published to pretty much no notice. I believe this is precisely because of the limp, vague visions put forward in those books. Wide-ranging in their criticisms but terminally hazy in their jargon-laden biopolitical solutions, Hardt and Negri simply didn’t offer anything for movement members or the public to latch on to. If you are going to lay a claim to daemonic (non-banausic) thought, you have to do better than that. You need to offer a glimpse at Truth. Plato knew that, at least.