[This is an old review which I’m bumping because Open Letters has recently republished this book, for which I am grateful. It has stayed with me as one of the greatest Communist allegories I have read.]

Ludvik Vaculik has very little in common with Milan Kundera, or Ivan Klima, or Josef Skvorecky. Those are three of the biggest names in modern Czech writing, and they all combine a historical awareness with a fondness of heavy allegory. All deal with political subjects explicitly, but the material isn’t polemical, especially with Kundera.

The Guinea Pigs is different. It shuns any specific realism and has a surrealistic streak that has more in common with the samizdat literature of Czechoslovakia, like that of Lukas Tomin, but it is handled with such steely calm that surrealism doesn’t predominate.

Very little predominates over anything else; Vaculik applies Kafka’s style of ambiguous symbolism to totalitarian allegory with huge success. Next to the more explicit and/or fanciful allegories of Koestler, Makine, Pelevin, and others, Vaculik’s book is more intimate, less graspable, and far more striking. Kafka wrongly gets posited as a political or humanitarian allegorist, when his stories are rather personal series of images and processes that cannot be conclusively unlocked. Vaculik really is an allegorist.

Vasek, the narrator, works as a bank clerk in Prague, where people regularly steal money to make their living. He buys some guinea pigs for his children, but becomes obsessed with them himself: specifically, with their responsiveness (or lack thereof), their tolerance for adverse situations, and their seeming absence of personality short of gut reactions (like biting).

Halfway through the book, he is torturing them. The tortures aren’t beastly; what makes them acutely discomfiting to read is the narrator’s sickly mental state:

As the water rose, the guinea pig rose too, although it ordinarily doesn’t stand around on its hind legs, but rather squats like a hare or a rabbit. Now it stood on its hind legs, though, and raised its body above the water level. “Well, how are things?” I said gently. “Not so hot,” it replied, and rocked slightly in the waves. But it was still standing on its feet. It raised its head, up, in my direction.

I turned off the water. The silence was a relief. Only the sewer gurgled. I became aware of a pressure in my skull, a drunken excitement that I had never known before, a tremor of the nerves. I reached into the pit. With my miraculous power, I lifted Ruprecht into the air, he grabbed my hand with all his claws, he hung on. I picked him up to my cheek and I could hear his tight, thin, wheezing breathing. I also whispered to myself, “We’re saved.”

Vaculik walks a very fine line between a symbolism that is too schematic and intrinsically arbitrary, on the one hand, and an overdramatization of the Vasek’s treatment of the guinea pigs, on the other. Sometimes he loses control and takes the easy way out, as when Vasek tells his wife that he’s turning into a guinea pig. But much of the time he carefully piles on the ambiguities and mysteries.

Vasek’s strange relationship with his workplace and his superiors, including the venerable Mr. Maelstrom, whose name signifies the slow degradation of the surrounding environs, as money disappears after it is confiscated from the workers who stole it, as the guinea pigs meet random fates in the face of Vasek’s disinterested curiosity, and as Vasek meets his fate as he loses all his emotional capacities.

The end of the book is an explicit reference to the end of The Trial, and there are other segments that resemble it, like Maelstrom’s discourse on circulation, which could be a first cousin to the speeches of the lawyer and the priest of The Trial. The flow and process of the book is not as effortless as in Kafka, but Vaculik manages a stricter version of a process Kafka never fully embraced, that of removal. It’s not there in his novels, and the two short stories in which the process of removal predominates–“The Metamorphosis” and “A Hunger Artist”–are actually atypical. By placing the senseless guinea pigs front and center, Vaculik sets his aim quite early, and follows the arc without error. What remains at the end is not language, as with Beckett, but a physical void.

Books like these that strive for an almost noetic effect can have an initial impact that is not lasting, but guardedly, I will say that it ranks far beyond any of the other Czech writers mentioned, and alongside Kleist and Gogol.

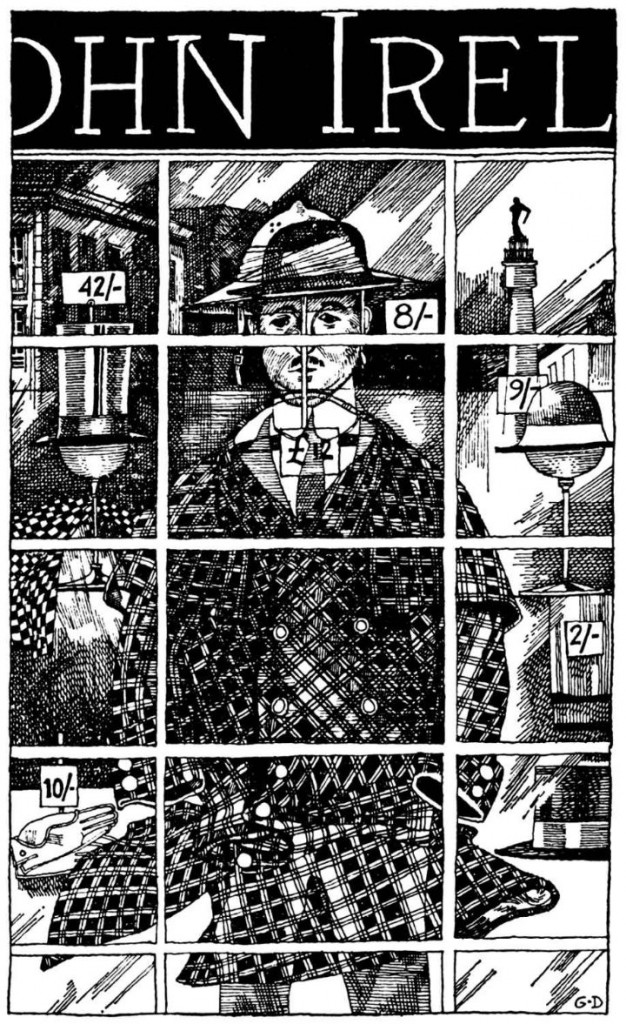

![guinea_large[1]](http://www.waggish.org/wp-content/uploads/2003/04/guinea_large1.jpg)