Ernest Gellner’s Words and Things was Gellner’s scathing attack on ordinary language philosophy. It caused a fuss in 1959 and made Gellner’s name after Gilbert Ryle refused to review it and Bertrand Russell angrily defended it. How valid was the critique?

This is not just a historical exegesis, but an object lesson in the hopes that older disputes no longer quite so relevant to us can guide us to principles useful in current debates where we lack the benefit of distance. In short, Gellner is right on sociology and wrong on the philosophy, especially Wittgenstein. But the reasons for that are complicated.

Ordinary language philosophy was the mid-century movement represented nowadays by J.L. Austin and Gilbert Ryle, though it’s telling that Gellner quotes some of the lesser-known lights of that scene to make his most scathing attacks. In addition to Austin and Ryle, he rips on the far more obscure G.J. Warnock and John Wisdom, who do give Gellner some of his juiciest material. I haven’t read either of the latter two, but it seems entirely possible they were strident, less than brilliant exponents of the linguistic turn.

Ryle doesn’t offer up such foolish statements, so Gellner’s critique is broader there: Ryle has drawn the focus away from science and toward trivialities by wanting to analyze the concept of mind rather than mind itself. And Austin is simply a knight-errant whose obsession with the most quotidian of conversational gambits is theological angel-counting.

Gellner has generally kind words for logical positivism and A.J. Ayer and Bertrand Russell, who wrote the preface, again putting him dangerously close to the movement he is attacking. And he ignores perhaps the strongest and most wide-ranging mind to be associated with the movement, P.F. Strawson, as well as Americans like Quine. So it is a bit of a chimera that Gellner is attacking, in that he attributes to a collective a dogma that perhaps even its most strident members didn’t fully adhere to.

One could accuse Gellner of cherry-picking, and I think it’s a fair charge, but I think it’s more enlightening to see that Gellner was criticizing a culture, not a philosophy, one that existed at Oxford in the 1950s and that Gellner experienced first hand. Gellner was a social scientist more than he was a classical philosopher, and his rage is less about ideas per se than about the people who hold them and how they hold him. As an avowed disciple of what he termed Enlightenment Fundamentalist Rationalism, he was guided, more than anything else, by the idea of fallibility and the need for constant doubt:

There are no privileged Sources or Affirmations, and all of them can be queried. In inquiry, all facts and all features are separable: it is always proper to inquire whether combinations could not be other than what had previously been supposed. In other words, the world does not arrive as a package-deal—which is the customary manner in which it appears in traditional cultures—but piecemeal. Strictly speaking, though it arrives as a package-deal, it is dismembered by thought.

Cultures are package-deal worlds; scientific inquiry, by contrast, requires atomization of evidence. No linkages escape scrutiny. Empiricist theory of knowledge claimed that information actually arrives in tiny packages (which is false as a descriptive account); but the lesson learnt was that it should be treated as if it was so broken up. Such breaking up of clusters fosters critical revaluation of world-pictures.

This reexamination of all associations destabilizes all cognitive anciens règimes. Moreover, the laws to which this world is subject are symmetrical. This levels out the world, and thereby ‘disenchants’ it, in the famous Weberian expression. This is the vision. Note again, it desacralizes, disestablishes, disenchants everything substantive: no privileged facts, occasions, individuals, institutions or associations. In other words, no miracles, no divine interventions and conjuring performances and press conferences, no saviours, no sacred churches or sacramental communities. All hypotheses are subject to scrutiny, all facts open to novel interpretations, and all facts subject to symmetrical laws which preclude the miraculous, the sacred occasion, the intrusion of the Other into the Mundane.

But what is perhaps absolutized and made exempt is the method itself. And the method leaves its shadow on the world: it engenders an orderly, symmetrical Nature. The orderliness of inquiry leaves its shadow, and appears as an orderly, unique nature. This is the proper sense which is to be attributed to the Kantian doctrine that we ‘make’ our world: an orderly, systematic, law-bound Nature is really the shadow of our cognitive procedure.

Ernest Gellner, Postmodernism, Reason, and Religion: I Choose You, Bachelorette #2

[Okay, I made up the subtitle.]

What Gellner could not stand were closed systems of thought that were not vulnerable to evidentiary invalidation: religion, Marxism, and psychoanalysis being three popular forms. Behind Gellner’s sociological description of the maneuvers employed by his nemeses lies his true frustration:

There is an undeniable element of truth in Polymorphism, both logically and empirically. As a matter of simple fact it is true that languages are complicated and consist of a variety of activities. It is also, perhaps, a necessary truth that any language that does anything worth while has to contain elements or tools of radically different types, and so cannot be internally entirely homogeneous and simple. Nevertheless, the exaggerated use of Polymorphism * by Linguistic Philosophy is disastrous and unjustifiable. Its weaknesses are similar to those of the three fallacies outlined previously with which it is closely associated. It is an attempt to undermine and paralyse one of the most important kinds of thinking, and one of the main agents of progress, namely intellectual advance through consistency and unification, through the attainment of coherence, the elimination of exceptions, arbitrarinesses, and unnecessary idiosyncracies. It in effect tends to underwrite all current concepts, however useless, anachronistic, inconsistent. For linguistic philosophers conceive their philosophical thought to be the undermining of general models and of models as such, as models-only the actual ungeneral description of an usage is philosophically “aseptic”, and commendable.

*The “57 Varieties” way of doing philosophy, as it has been wittily described by Professor S. Kömer.

Ernest Gellner, Words and Things

He no doubt saw ordinary language philosophy as another, as it “dissolved” one problem after another as linguistic rather than real. This for Gellner is cowardice. Making G.E. Moore into a Chance the Gardener figure, he compares him to Wittgenstein’s ideal:

Some philosophers have considered the deliberate suspension of belief, of the natural attitude, to be of the essence of philosophy. Husserl called it the epoche, a kind of putting-of-the-world-in-brackets and suspending judgment so that one could have a better look.

The essence of Moore is a kind of inverted epoché. He refused to put the world in any brackets.

Moore’s inverted epoché, his conviction or principle that things in general were substantially as they seemed, reappears in Wittgenstein and in Linguistic Philosophy proper with a rationale –namely, that assertions to the effect that things are radically other than they seem are always misuses of language. In brief, Moore displayed many of the characteristics of Linguistic Philosophers, without being led to them by the ways and reasoning of Wittgensteinianism. He did by nature that for which Wittgenstein’s Revelation found reasons.

One might say that G.E. Moore is the one and only known example of Wittgensteinian man: unpuzzled by the world or science, puzzled only by the oddity of the sayings of philosophers, and sensibly reacting to that alleged oddity by very carefully, painstakingly and interminably examining their use of words. . . .The philosophical job is to persuade us of the adequacy of ordinary conceptualisations. It is the story of Plato over again–only this time it is the philosopher’s job to lead us back into the cave.

Ernest Gellner, Words and Things

For Gellner, this “adequacy” is synonymous with complacency and cultural conservatism. I.e., it is the attempt of the Oxford don to keep the world as the comfortable place that it is.

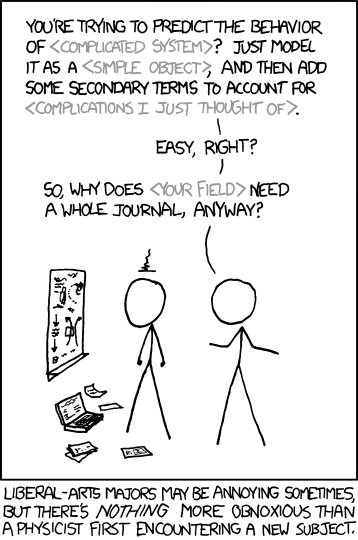

I am a bit sympathetic to this critique, as I suspect the ordinary language orthodoxy of the 1950s genuinely was overbearing and vexing to those upstarts who wished to pursue a less linguistic direction. Yet of course anything can serve as a closed system, if its believers are sufficiently recalcitrant, and any orthodoxy can be and often is overbearing and vexing to upstarts. You don’t need Duhem, Quine, and Kuhn in order to believe that people generally are hesitant to lose faith in the systems to which they have pledged themselves. People are apt to overextend their systems as well. (See C.D. Darlington and, time and again, David Hume and xkcd.)

Nevertheless, Marxism and psychoanalysis, among others, have attracted somewhat more cult-like followings than other systems. It’s probably a good thing Gellner didn’t spend too much time around Heideggerians, otherwise we would have gotten a book on them. Gellner limits himself to a single dismissive remark:

On the side of Continental philosophy, a greater and greater cult of paradox and obscurity, an appetite which feeds on what it consumes and, as with a galloping illness, hardly allows the imagination to conceive its end: who can outdo Heidegger?

Ernest Gellner, Words and Things

The issue is to what extent this cult-like environment is entailed by the system at hand. The criterion that Gellner uses to judge the level of closure of philosophical systems, which I think is a good one, is that of mysticism. At one end is the scientific method by which everything is (supposedly) falsifiable; at the other end is wholly unjustified religion. These two quotes, both of which invoke the phrase “curiously reminiscent,” should give some idea of where ordinary language philosophy stands for Gellner on that spectrum:

The doctrine that philosophy must wither away as we become acquainted with the patterns of our use of words is curiously reminiscent of the Marxist view that the State will wither away.

This main fallacy of Wittgenstein’s which remained with him throughout his life can indeed be expressed more dramatically as the notion that there is such a thing as “seeing the world rightly”. Thus Linguistic Philosophy, the doctrine that philosophy is an activity, is a spiritual exercise that confirms the faith which calls for the exercise to begin with. It is in this respect, as in others, curiously reminiscent of psychoanalysis.

Ernest Gellner, Words and Things

The ultimate bounty of Words and Things is Wittgenstein, whom Gellner would go after in other books as well. There is no question that Wittgenstein is an arch-enemy for Gellner just as much as Russell is a comrade-in-arms. I think Gellner saw Wittgenstein’s abandonment of the semi-reasonable (yet still too mystical) logical atomism of the Tractatus as a betrayal of the human obligations of doubt and secular progress, in effect a turn to religion.

Wittgenstein and his ordinary language followers represent, to Gellner:

- The abandonment of serious, relevant issues for conjured, spurious ones.

- The unquestioning faith of a mystic and the corresponding influence on blind followers.

These are two different charges, which I’ll call Charge (1) and Charge (2). Gellner co-mingles them but especially with Wittgenstein they need to be separated. My own view is that the first charge is ungrounded but that the second one is at least somewhat legitimate.

As to Charge (1) of spuriousness, Gellner overlooks the internal developments within logical positivism, and the difficulties that Carnap’s Aufbau and other attempts to regiment the world had faced. In fact, he does attack logical atomism as an early example of Wittgenstein’s faith-based reasoning, with Wittgenstein assuming that there are logical simples out there but not needing to go to the trouble of finding any. But Gellner doesn’t seem to want to acknowledge the implications of the failure of logical positivism and verificationism.

In addition, Gellner gets Wittgenstein wrong on a number of points, a problem that persists when he treats Wittgenstein’s later work. This is probably the most damning aspect of the book and the one that still causes people to dismiss it. I can’t defend Gellner here: he felt the need to go after the substance as well as the context, and he couldn’t be bothered to give it a fair shot. To be fair, Wittgenstein is seriously difficult and many of his adherents got him wrong too, and many still aren’t sure if they’re even right; but in general, the closer Gellner gets to Wittgenstein’s philosophy, the less convincing he is.

But in separating language philosophy from all other philosophical problems, Gellner also ignores the more general continuum that was being set up. Language, reality, and logic were not coalescing in the way that was promised, and it was not producing an “orderly, unique nature.” Godel’s blow to systems of logic showing them to be necessarily incomplete was perhaps the most crushing inner defeat, but language itself was refusing to conform as well. In this way Gellner was very similar to Russell, who saw the problems Wittgenstein raised with his Theory of Knowledge, but could not bring himself to reject the general empiricist basis behind them. (See David Pears’ The False Prison for more on this.)

Because syntactic or indeed semantic theories of language haven’t really worked out, and pragmatics have become more and more important, you can call Austin et al. naive, dogmatic, boring, or just plain sloppy, but you can’t quite call them wrong, at least not in the way one would call logical positivism wrong.

The problem is that Gellner’s Enlightenment Fundamentalist Rationalism sets up very strict criteria by which one can make sweeping statements about things like the worthlessness of a school of philosophy, and human languge is such a mess that Gellner’s attempt to hold the fort on reasonably simple, naive theories of meaning cannot clear the bar that his own principles have set for him.

That leaves Gellner other avenue of attack for Charge (1), his objection to Pyrrhonistic and therapeutic attitudes of ordinary language philosophy. I do not see this attack as sufficiently grounded either, as science has offered similar prescriptions. The healing of our “folk psychological” ideas is just one of the more prominent recent examples of “seeing the world rightly.” Hence why Dennett’s Consciousness Explained was dubbed Consciousness Explained Away, Consciousness Ignored, etc. These attitudes may be better grounded scientifically, but the attitudes remain similar.

And Pyrrhonic and therapeutic attitudes are hardly new: Epicurus, Nagarjuna, Sextus Empiricus, Lucretius, and many others have always offered the claim that truth would set us free from at least some of our worries and obsessions. These attitudes, when deployed pathologically, are an offense to knowledge and curiosity, but Gellner simply slams the attitudes in toto without allowing for their inevitable presence in all domains. They can never be stamped out. I’m sure Gellner knew this, but his enthusiasm got the better of him.

Onto Charge (2), of the mythification of Wittgenstein. Everything I have read suggests a strong degree of truth to the veneration and almost deification of Wittgenstein. He had an aura of remote brilliance about him and people speak of attending his classes as they would of attending the speeches of a prophet. I think Gellner is very psychologically keen about Wittgenstein.

This main fallacy of Wittgenstein’s which remained with him throughout his life can indeed be expressed more dramatically as the notion that there is such a thing as “seeing the world rightly.”

Wittgenstein was indeed driven by a need for certainty, for clarity, for indisputable assertions. There is no doubt this was a pathological need, and it informs the less attractive aspects of his philosophy: a general arrogance and an unwillingness to accept, even momentarily, provisional or partial measures in explanations and analyses. Both of these are present in his demand to see the world rightly.

Wittgenstein’s brilliance and integrity prevented him from taking easy solutions, however, and Gellner does not seem to have realized this, presumably because he did not take Wittgenstein’s project seriously. Wittgenstein’s stubbornness and general refusal to accept criticism except from within does not make it any easier, but the fact remains that Wittgenstein could not allow himself to do what he continually said he wanted to do, which is give up philosophy. He wouldn’t stop until he knew he saw the world rightly, and I’m pretty sure he never would have believed he did. Gellner has made an accurate diagnosis but has misstated the symptoms.

Yet Wittgenstein’s personality did engender a more rigid orthodoxy, which was not helped by the stridency of Ryle. Again, however, Gellner goes too far in conflating philosophy and culture. The orthodoxy of computational linguistics was just as strong for many years, yet it did not arise from any particular mysticism of beliefs, just from a remarkably charismatic and brilliant founder.

Wittgenstein was an exceptional case, however, and the combination of his gnomic discourse and his yearning, spiritual frustration was captivating to some and toxic to people like Gellner. (I don’t believe Gellner ever met Wittgenstein, but that he formed an idea of him based on interacting with his acolytes, an idea perhaps even more mythic and titanic than the reality.) It is right to be wary of any such elevation, and it is here that Gellner gets closest to explaining the cultural etiology of the more mediocre language philosophy he is attacking, and the blind faith that does play a part in it.

It’s a curious error to conflate ideas (Charge (1)) and culture (Charge (2)), and particularly curious when a keen social scientist like Gellner makes it. It’s not the only time he did it: The Psychoanalytic Movement: The Cunning of Unreason indicts Freud and his followers on similar grounds, though with far more success. Freud, like Wittgenstein, was a near-demagogic bringer of truth who also suffered from acute self-doubt and revised his own theories repeatedly, while bridling at the slightest criticism from others. In both cases, Gellner ties the figures and their followers too rigidly to the ideas in play, as though there was an exact parallel correspondence between the sociological power dynamics at work and the underlying theories themselves.

It produces a peculiar sort of alienation: people are expressing and asserting themselves through ideological systems and forms of argument rather than through emotional dynamics. My own belief has generall been that this gets it the wrong way round: ideological reconstructions are post hoc justifications for personal and emotional conflicts that owe little (but not nothing) to the intellectual matters at hand. The ideas coyuld have easily been different; the emotions and games of power are so often the same.