James Joyce made the superimposition of conflicting patterns one of the central principles of both Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. (You can see it in Portrait as well, but nowhere near to the extent.) While he drew on Dante’s schematic cosmology as a model for organizing huge and diverse amounts of material, he drew from Shakespeare the notion that uncertainty, indeterminacy, and outright contradiction could give immense strength and depth to the effect of a work on readers.

Unlike Shakespeare, Joyce could not hide his life from his readers. People were now far more interested in the life of the artist, and documentation was too easily had. But rather than trying to mask his intentions, he could overload a work with as many conflicting and indeterminate moments, motifs, and significations as possible. Schemata that came to mind after the basic construction of a work, like the infamous Ulysses schema that Joyce gave to Stuart Gilbert that has held too much sway ever since, were just additional bricks to add to the consternating edifice. (Note the somewhat variable Linati schema.)

This gave rise to the peculiar modern criticism that Joyce does not say anything. Harry Levin was both perceptive and naive in 1939 when he reviewed Finnegans Wake and said:

Among the acknowledged masters of English—and there can be no further delay in acknowledging that Joyce is among the greatest—there is no one with so much to express and so little to say. Whatever is capable of being sounded or enunciated will find its echo in Joyce’s writing; he alludes glibly and impartially to such concerns as left-wing literature (116), Whitman and democracy (263), the ‘braintrust’ (529), ‘Nazi’ (375), ‘Gestapo’ (332), ‘Soviet’ (414), and the sickle and the hammer (341). The sounds are heard, the names are called, the phrases are invoked; but the rest is silence. The detachment which can look upon the conflicts of civilization as so many competing vocables is wonderful and terrifying. Sooner or later, however, it gives a prejudiced reader the uncanny sensation of trying to carry on a conversation with an omniscient parrot.

Harry Levin, “On First Looking into Finnegans Wake” (1939)

The rest is anything but silence. Joyce was aware of the implications of all of these terms (and was hardly impartial about them). He created breathing space not by failing to elaborate on these terms, but by invoking as many associations with them as possible, fully aware of their contradictions.

This sort of technique agglomerates into daunting complexity, but I don’t think the method is meant to complex, nor did Joyce intend it to be. It doesn’t need to be complex for striking effect. One very central opposition/superimposition is the idea of linear and circular motion. Joyce conflates the two very frequently in both Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. The very basis of Ulysses, a single day, is a canonical example: at the end of the day, one cyclically returns to where one started, while having progressed linearly to a new day. Likewise, Odysseus returned home on a circular journey while experiencing the linear movement of plot. Very simple.

But Joyce also applies the device repeatedly at a lower level. (I hesitate to use the dread word fractal, but it’s appropriate in this case.) The novel is constructed in a symmetrical form: 3 chapters, then 12 chapters, then 3 chapters. Yet the mapping of the styles individual chapters in the first and final sections is not done in reflection:

- Chapters 1 and 16 (Telemachus and Eumaeus): third-person narration.

- Chapters 2 and 17 (Nestor and Ithaca): interrogative dialogue.

- Chapters 3 and 18 (Proteus and Penelope): first-person interior monologue.

And yet chapter 1 was given the sobriquet “Telemachus” rather than chapter 3, which would make more sense given this parallel, as Stephen is Telemachus and Molly is Penelope. But it would wreck the larger symmetry of having a book called Ulysses that begins with Telemachus and ends with Penelope. Joyce had no problem with breaking patterns for the sake of establishing other patterns.

Likewise, the middle 12 chapters divide into sets of 3, with every third chapter (6, 9, 12, 15–Hades, Scylla and Charybdis, Cyclops, Circe) having a Big Plot Event, conflict, or climax relative to the remaining, somewhat more subdued chapters, even as the style and material of the chapters is continually progressing into new and generally more abstruse territory. The “squaring of the circle” theme that preoccupies Bloom is also a reflection of how the linear is coextant with the cyclical, but not identical. There are many, many other instances.

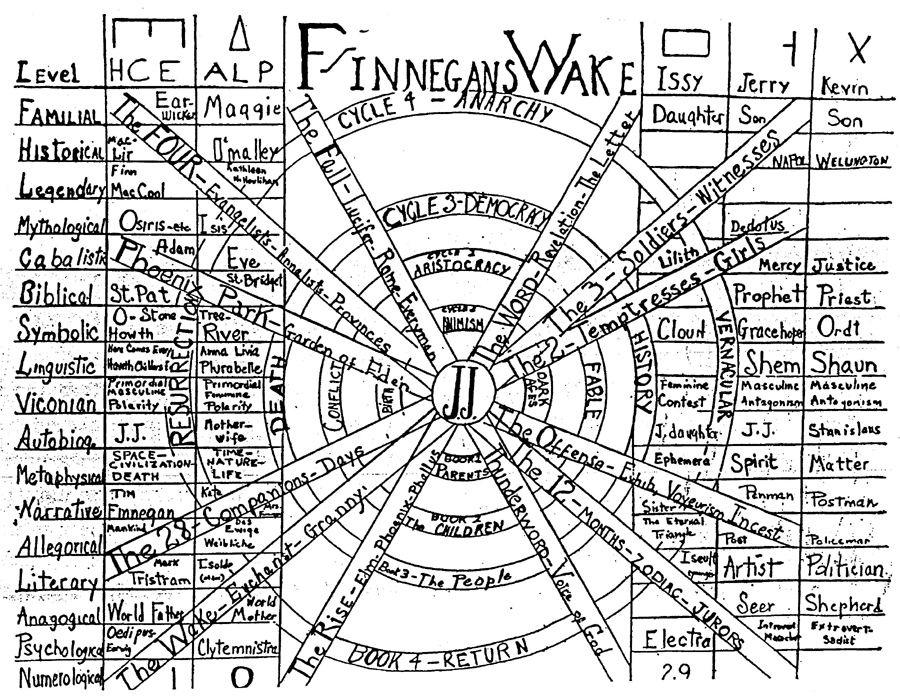

And I think that this fundamental overlay of linear and cyclical remains, more or less unaltered, in Finnegans Wake. I believe it to have been a fundamental component of Joyce’s metaphysics and cosmology, and I believe that Vico was primarily a way for Joyce to obtain a central cyclical structure for history. Richard Ellmann quotes Joyce as saying, when asked if he believed in Vico’s New Science, “I don’t believe in any science, but my imagination grows when I read Vico as it doesn’t when I read Freud or Jung.” The content of Vico’s cycle, while useful, was less crucial than its form.

But even though Joyce gave Finnegans Wake a clear cyclical structure by having its first sentence complete its final sentence, the linearity is there everywhere as well, from Jaun’s evolution, journey, and quest narrative in the third part to the very process of children growing up and defeating/killing/usurping their father. The one-way journey from birth to death, from child to adult, is neither trumped nor negated by a cyclical view of history. (Perhaps it’s only in infinity that endless similar recurrences of a process can result in occasional identical instantiations of that cycle; again, think of the squaring of the circle, which would only be possible in infinity.) If the cyclical aspect seems overly pronounced at times, it’s only because the linear aspect is so often the default.

The timescale of the book works similarly. Two of the timescales in the Wake is from 6pm to 6am and sunset to sunrise. Sunset and sunrise are mirror reflections in time and in space, but the sun’s one-way motion across the sky accounts for it rising in the east and setting in the west, it having made a reverse journey to return to its place of origin while maintaining forward motion, by virtue of the extra dimension. The half-revolution of the Earth covered by this time period covers exactly half the journey, 180 degrees, from one linear extreme to the opposite, before reversal toward the point of origin begins.

Joyce also used the Egyptian Book of the Dead as a foundational text for Finnegans Wake, and Egyptian mythology has a near-perfect analogy for this process. In Egyptian mythology, Ra the sun god dies at the end of each day in the west and makes a journey through the underworld each night to return to the east, where he is reborn. (He makes the journeys on boats, no less, allowing for Joyce to fit in the female aspect as the water.) This fits uncannily with Joyce’s ever-reborn masculine, eternal feminine, and the identification of the day-night cycle with that of life and death, rise and fall, civilization and breakdown.

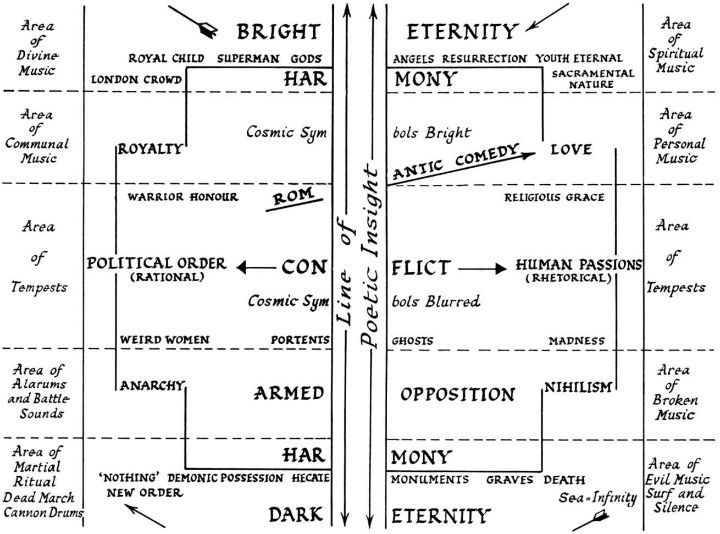

The motion motifs pile up to immense complication, since Joyce works this superimposition in at many levels. One combination of circular and linear motion then becomes part of a larger series of circular and linear motions which can reflect, mirror, or reiterate the original combination; and so on and so forth. Joyce makes much hay of reflection, mirrors, symmetry and asymmetry, twins and opposites, and so on.

Appreciating this complexity does not require seeing all these superimpositions or even most of them. Joyce knew this would be impossible for a reader or even a group of readers, so he chose an approach that would demonstrate this near-infinity of superimpositions through a fundamentally simple method that could organically grow into immense complexity. This creates the secular sense of awe that Joyce inspires in me. I see it as Joyce’s ultimate expression of the attempt to comprehend the metaphysical infinite with the finite resources of the mind and portray it in art.

Richard Ellmann, in his biography of Joyce, quotes a passage of Benedetto Croce, which Joyce had certainly read, that is quite apt:

Croce’s restatement of Vico, ‘Man creates the human world, creates it by transforming himself into the facts of society: by thinking it he re-creates his own creations traverses over again the paths he has already traversed, reconstructs the whole ideally, and thus knows it with full and true knowledge,’ is echoed in Stephen’s remark in Ulysses, ‘What went forth to the ends of the world to traverse not itself. God, the sun, Shakespeare, a commercial traveller, having itself traversed in reality itself, becomes that self…. Self which it itself was ineluctably preconditioned to become. Ecco!‘