That is the opening to Hiroshi Teshigahara’s The Man Without a Map, better known in its English novel translation as The Ruined Map. The amazing cutup music is by Toru Takemitsu.

It’s the final of four collaborations between Teshigahara and novelist/screenwriter Kobo Abe, who also produced the gorgeous The Woman in the Dunes and the surreal and disturbing The Face of Another. If there’s a problem I have with those two, it’s that Teshigahara always seems to be the sanest of the contributors: while Takemitsu and Abe are straining at the margins of convention, Teshigahara seems more content to play things straight, filming things as though they were conventional dramas with haunting scenery. I don’t think it’s coincidence that Teshigahara’s last film was about a master of tea ceremonies.

In The Man Without a Map everything falls apart. The movie isn’t a disaster and has enough to hold interest, but it is a failure. Teshigahara seems uninterested in the material and gives it little visual flair, while the ambiguities of the earlier films now spill into incoherence. The basic story is of a detective hired to investigate a missing man, Nimuro, by Nimuro’s sister. But the noir tropes dissolve as quickly as they’re introduced. Nimuro’s brother shows up to give the detective secret information that the sister did not reveal. Nimuro’s wife appears and disappears. Nimuro was involved with some bootleg food stalls possibly associated with the mafia, who beat up the detective. A man tempts the detective with nude photos he claims were taken by the Nimuro, but were they? Do they have anything to do with Nimuro?

That last mysterious man, who throws out clues that may be red herrings, who may not be related to the case at all, is the closest to the heart of the movie. The detective is hostile to any sort of conventionality, and by the end of the film, the noir tropes appear to be springing up because he wills them to do so, even if they don’t make sense. By the end of the movie (spoiler alert!), the mystery man announces his attention to commit suicide on the phone to the detective, who is annoyed with him and ready to hang up. The detective asks if he’s written a note: “No. They’re not exactly easy to write.”

I laughed, but I take it to mean that in trying to write some sort of lives for themselves outside the margins, Nimuro, the detective, and the mystery man have unwoven the fabric of their lives and so they fall apart, like the movie. Similar disintegrations happened in the earlier films by Teshigahara and Abe, but they didn’t reach the level of the plot, as they do here. Because, it appears, Teshigahara is not on board with Abe’s conceit, the film falls apart as it attempts to fall apart.

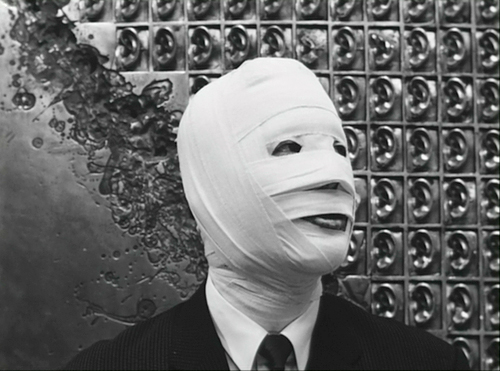

It makes me wonder what would have happened if a more avant-garde filmmaker of the time like Terayama, Oshima, or Yoshida had worked with Abe’s material–this or Abe’s far crazier The Box Man, where Abe abandons all pretense to psychological realism. The Face of Another is the most successful of their collaborations because Teshigahara is able to transform a “normal” world into one that becomes increasingly frightening and chaotic for the faceless protagonist. But once the normal is far out of sight, visual innovation has to substitute for the normal reference points of identification, and in The Man Without a Map, it doesn’t happen.

And just to conclude, here is the trailer for The Woman in the Dunes, featuring Takemitsu’s eerie, remarkable electroacoustic score: