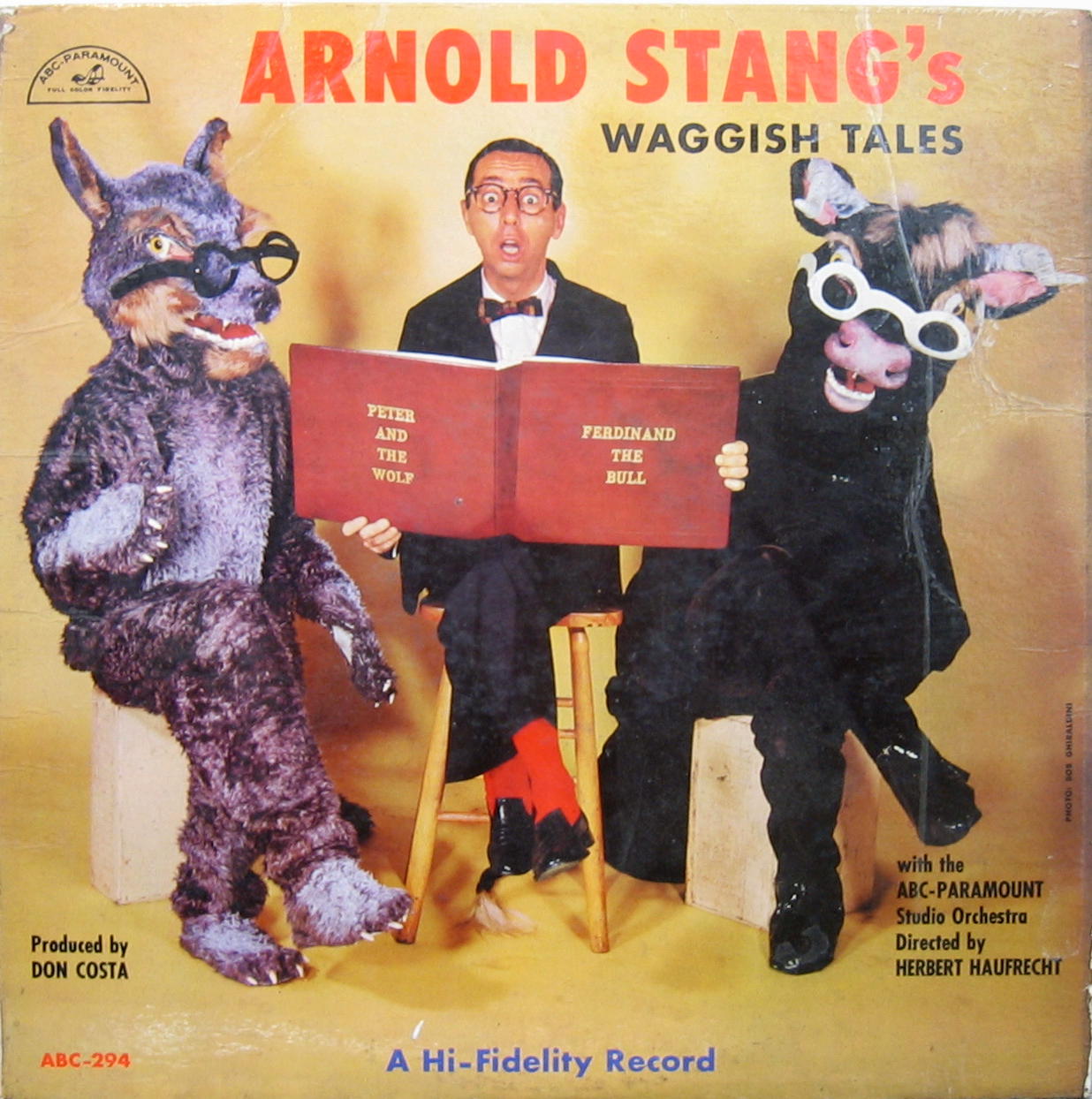

Arnold Stang, Milquetoast Actor, Dies at 91

Spiritual forebear?

(Thanks to the anonymous person who sent me this ages ago.)

Arnold Stang, Milquetoast Actor, Dies at 91

Spiritual forebear?

(Thanks to the anonymous person who sent me this ages ago.)

I saw Heiner Goebbel’s odd Stifters Dinge this weekend (made odder with the persistent head cold I’ve had), and though I think it’s senseless to try to give a concrete analysis of it, one part jumped out at me, an interview with Claude Levi-Strauss where he says that there is nowhere left unexplored in the world, no remaining frontiers. I don’t think he’s right, but humanity is definitely at a place where we finally think of the whole planet as our home rather than any one part of it. And so…

If we have to seek man’s origin in the category of animals that ‘flee,’ then we can comprehend that before the change of biotope [from jungle to savanna] all signals that set off flight reactions would indeed have the power of fear but would not have to reach the level of a dominating condition of anxiety, as long as mere movement was available as a means of clarifying the situation. But if one imagines that this solution was no longer, or no longer constantly, successful, then from that point onward the situations that enforced flight either had to be dealt with by standing one’s ground or had to be avoided by means of anticipation.

Hans Blumenberg, Work on Myth 1.1

So while Hegel thinks the primary will of humanity is desire, for Blumenberg the primary motive of primitive humanity is getting the hell out of Dodge. And when we settled down and no longer ran from place to place, an underlying anxiety originated of the anticipation of having to pick up sticks and run. (Blumenberg is more prosaic than Heidegger; he thinks life is tough enough on its own without the problems of Dasein.) And as long as we could imagine that flight, could imagine packing up and rebuilding elsewhere, the anxiety could be kept in check.

But I wonder: when you’ve filled up the planet and you know you’re stuck on it and you start to see assorted disaster scenarios that offer no refuge to start over (be they nuclear, environmental, or otherwise), what does that do to the anxiety? There’s no flight left (except to other planets, the fantasy of some optimists).

13 August 1910. Before I went to sleep, one or two other things occurred to me about my way of working (in the novellas). What matters to me is the passionate energy of the idea. In cases where I am not able to work out some special idea, the work immediately begins to bore me; this is true for almost every single paragraph. Now why is it that this thinking, which after all is not aiming at any kind of scientific validity but only a certain individual truth, cannot move at a quicker pace? I found that in the reflective element of art there is a dissipative momentum–here I only have to think of the reflections that I have sometimes written down in parallel with my drafts. The idea immediately moves onward in all directions, the notions go on growing outward on all sides, the result is a disorganized, amorphous complex. In the case of exact thinking, however, the idea is tied up, delineated, articulated, by means of the goal of the work, the way it is limited to what can be proven, the separation into probable and certain, etc., in short, by means of the methodological demands that stem from the object of investigation. In art, this process of selection is missing. Its place is taken by the selection of the images, the style, the mood of the whole.

I was annoyed because it is often the case with me that the rhetorical precedes the reflective. I am forced to continue the inventive process after the style of images that are already there and this is often not possible without some amputation of the core of what one would like to say. I am only able at first to develop the thought-material for a piece of work to a point that is relatively close by, then it dissolves in my hands. Then the moment arrives when the work in hand is receiving the final polish, the style has reached maturity, etc. It is only now that, both gripped and constrained by what is now in a finished state, I am able to “think” on further.

There are two opposing forces that one has to set in balance–the dissipating, formless one from the realm of the idea and the restrictive, somewhat empty and formal one relating to the rhetorical invention.

Tying this together to achieve the greatest degree of intellectual compression, this final stepping beyond the work in accordance with the needs of the intellectual who abjures everything that is mere words, this intellectual activity comes only after these two stages. Here the effect of the understanding is astringent, but here it is directed toward the unity of form and content that is already present whereas, whenever it is merely a question of thinking out the content, it dissipates. (Even in cases where one already has the basic idea around which everything is to be grouped, as long as the capacity for creating images is missing it will not work; if one restricts oneself in the extensive mode one goes to far in the intensive mode and one becomes amorphous.)

Diaries, p. 117

Note, contra Kant, ideas are formless content, rhetoric and language are form. I.e., if categories could be expressed we’re already expressing more than categories. This seems to be a German hermeneutic motif, the unspeakable but absolute idea beneath the text; Gadamer uses it too. Or to put it another way:

Jede Philosophie, die unsere Möglichkeiten des Zugangs zur Wirklichkeit von der Sprache abhängig macht – nicht nur vom Sprachbesitz überhaupt, sondern vom dem einer bestimmten, faktisch gewordenen Sprache, diese also als das Gesamtsystem aller Differenzierungen und Sichtweisen in der Erfahrung definiert, macht das Unsagbare auch im Sinne des noch nicht Gesagten heimatlos. Zugleich macht sie den Verdacht auf einen unüberwindbaren Relativismus der Alltagssprachen, der Nationalsprachen oder auch der wissenschaftlichen Sprachen unausweichlich. Nichts ist uns gegeben, was uns nicht durch Sprache vorgegeben wäre. Ist das befriedigend? Oder müssen wir nicht auch davon sprechen, daß die Sprache der Erweiterung unserer Erfahrung als der Einengung des Unsagbaren nachzukommen hat? Davon sprechen, daß sie umgebildet werden muß in bezug auf Leistungen, die im Sprachbestand noch nicht faktisch vorgegeben waren?

Blumenberg, Theory of an Unconceptuality, posth. 2008

(Thanks Antonia. And congratulations.)

Butcher’s Crossing is the most flawed, the most peculiar, and the most exuberant of Williams’ three mature novels (he disowned a first novel, which I have not read). Unlike the near-perfect tenors of the academic novel Stoner and Augustus, Butcher’s Crossing sees some significant shifts in tone over the course of the book. All three novels are Bildungsromans, but here Williams also attempts to tell the story of the decline of the American West as well. That is why, unlike the other two novels, it is not titled after the main character but the frontier town which provides the settings for the bookends of the novel.

Will Andrews is a Harvard student who, inspired by Emerson, drops out to find himself in the great West. After arriving in Butcher’s Crossing, he funds a hunting expedition to a distant valley in Colorado where a great herd of buffalo still remain, most of the other herds having already been hunted down and killed for hides. He is naive and for a time it seems he could be easily scammed, but the leader of the expedition, Miller, is serious, and after Andrews has a slight dalliance with a whore-with-a-heart-of-gold, they set out with two other grizzled men.

So the ground for an archetypal post-western has been laid, and the themes follow those that would be used (and overused) by Cormac McCarthy, Once Upon a Time in the West, and, of course, Stan Ridgway and Wall of Voodoo:

harshly awakened by the sound of six rounds of light caliber rifle fire followed minutes later by the booming of nine rounds from a heavier rifle, but you can’t close off the wilderness. he heard the snick of a rifle bolt and found himself staring down the muzzle of a weapon held by a drunken liquor store owner. “there’s a conflict,” he said. “there’s a conflict between land and people…the people have to go. they’ve come all the way out here to make mining claims, to do automobile body work, to gamble, to take pictures, to not have to do laundry, to own a mini-bike, to have their own cb radios and air conditioning, good plumbing for sure, and to sell time/life books and to work in a deli, to have some chili every morning and maybe…maybe to own their own gas stations again and to take drugs and have some crazy sex, but above all, above all to have a fair shake, to get a piece of the rock and a slice of the pie and to spit out the window of your car and not have the wind blow it back in your face.”

“Call of the West”

And that does somewhat mimic the arc in the book. Things get immediately dire as they have trouble finding water, and less than a third of the way into the book, things do seem to be shaping up for a sheer hellishness. But they find the water and the valley, and soon enough they are hunting (i.e., massacring in large numbers) buffalo. There is a sustained, 40-page description of the early days of the hunt that may be the most focused setpiece Williams ever wrote, and the turning point in Andrews’ character.

It came to him that he had turned away from the buffalo not because of a womanish nausea at blood and stench and spilling gut; it came to him that he had sickened and turned away because of his shock at seeing the buffalo, a few moments before proud and noble and full of the dignity of life, now stark and helpless, a length of inert meat, divested of itself, or his notion of its self, swinging grotesquely, mockingly, before him. It was not itself; or it was not that self that he had imagined it to be. That self was murdered; and in that murder he had felt the destruction of something within him, and he had not been able to face it. So he had turned away.

Such introspection is comparatively rare in the novel. Extensive and careful description is more common, but when it comes like it does here, it is strikingly abstract and visceral simultaneously. I don’t know if the effect is quite successful (thought it beats Cormac any day), but it’s certainly unusual. Williams resists any broad judgments of character. If Andrews is losing his humanity, then “humanity” is not an absolute value. He is freed from this sort of condescension towards the whore that he felt earlier in Butcher’s Crossing:

He saw her as a poor, ignorant victim of her time and place, betrayed by certain artificialities of conduct, thrust from a great mechanical world upon this bare plateau of existence that fronted the wilderness. He thought of Schneider, who had caught her arm and spoken coarsely to her; and he imagined vaguely the humiliations she had schooled herself to endure. A revulsion against the world rose up within him, and he could taste it in his throat.

Much, much later, after returning to Butcher’s Crossing, Andrews thinks back to this very moment and excoriates his younger self for his callow snobbery.

But returning to the plot: after the first day, things become blurry. They continue killing and skinning thousands of buffalo, and Miller, the expert guide and hunter, really wants to kill them all, even if it means leaving hundreds of skins to bring back to following spring. Unfortunately, it starts to snow, and they are stranded in the valley between the mountains all winter long.

As with the scenes where they nearly die of thirst, this would seem to be another potential hell, an existential misery. But Williams pulls back from this desolate Bresson scenario to aim more at The Wages of Fear, and six months of surely excruciating boredom pass fairly quickly without any Shining-like incidents. (In terms of page count, they pass more quickly than that first day of hunting.) I do think that this points to a fundamental stoicism in Williams’ work: for Augustus, Stoner, and Andrews, the hell comes from without, not from within. Events, not ennui, shape character.

Spring comes and they head back, and the book shifts again. Butcher’s Crossing has been transformed and ravaged by the end of the buffalo hide market, and Andrews’ growth is overshadowed by Miller’s desperate attempts to cope with the extinction of his chosen life from which he draws his pride. But the threads unravel; Williams can’t quite make Miller’s collapse mesh with Andrews’ development because Andrews does not learn anything new from it. Rather, Andrews finally does sleep with Francine, the whore from earlier, in a scene where Williams’ writing falls into the floridness described by Pynchon in critiquing his own first published story:

You’ll notice that toward the end of the story, some kind of sexual encounter appears to take place, though you’d never know it from the text. The language suddenly gets too fancy to read. Maybe this wasn’t only my own adolescent nervousness about sex…Even the American soft-core pornography available in those days went to absurdly symbolic lengths to avoid describing sex.

Thomas Pynchon, Introduction to Slow Learner

And in general, Williams’ writing is a little too lush and artful in Butcher’s Crossing, lacking the architectural precision of the later two novels. He is still a wonderful writer, but one is more conscious of him making an effort.

Butcher’s Crossing is a novel of discrete sections, and the ways they do and don’t fit together outline the refinements that Williams would make to his fictive approach. (Reading early work after later work, as I did with Thomas Bernhard’s “Walking”, sometimes helps to illuminate the best parts of the early work more vividly.) Williams abandoned the larger societal picture after this novel to focus on a single character and his milieu, and I suspect he found fault with the dual-pronged nature of Butcher’s Crossing as well. But he also abandoned the idea of the setpiece. It’s understandable, but based on that hunting section, he could have been a master at it. (He also learned how to write female characters; the women of Stoner are far more convincing than the one-dimensional Francine.)

But what of the greater themes of the book? I still think that Williams is pretty cagey about making statements and that the book requires that the author and the reader do not judge Miller and his kind too harshly. The West drives him and others to nihilism (explicitly voiced by a hide trader late in the book), but is this a fundamental truth, a consequence of their ravaging of the land, or just the aftermath of the extinction of their way of life? I do not see a definite answer. We do know that Andrews is changed, even if we don’t know quite what he becomes, and that is the heart of the book.

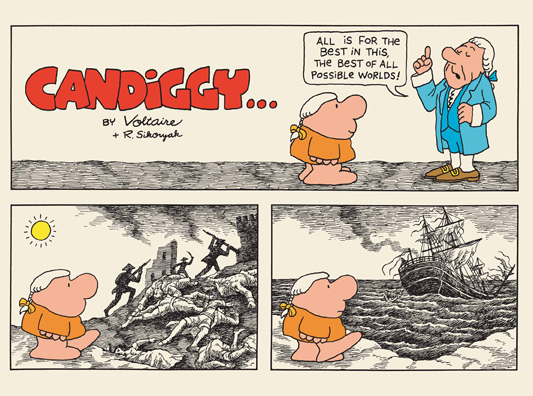

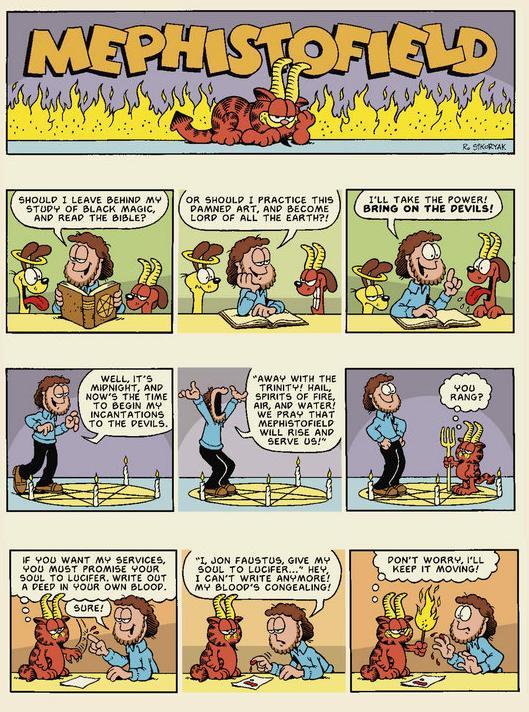

I’ve been reading Sikoryak’s parodies in one form or another since I was a teenager and saw “Good Ol’ Gregor Brown” (Charlie Brown does Kafka) in RAW. Finally they’ve been collected into a book. Here are two (they’re all pretty clever):

These high/low mixes don’t always travel well. How many people have any idea why Mr. Rochester speaks the way that he does in SCTV’s version of Jane Eyre? (“Whatever you do, Jane, don’t go up to the attic. I wouldn’t want you to get…murdered!”)

© 2025 Waggish

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑