In Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, the Lordship and Bondage (aka Master/Slave) passage frequently receives the most attention, but the sequence that has weighed most heavily on my mind in recent years has been the later discussion of the beautiful soul (schöne Seele).

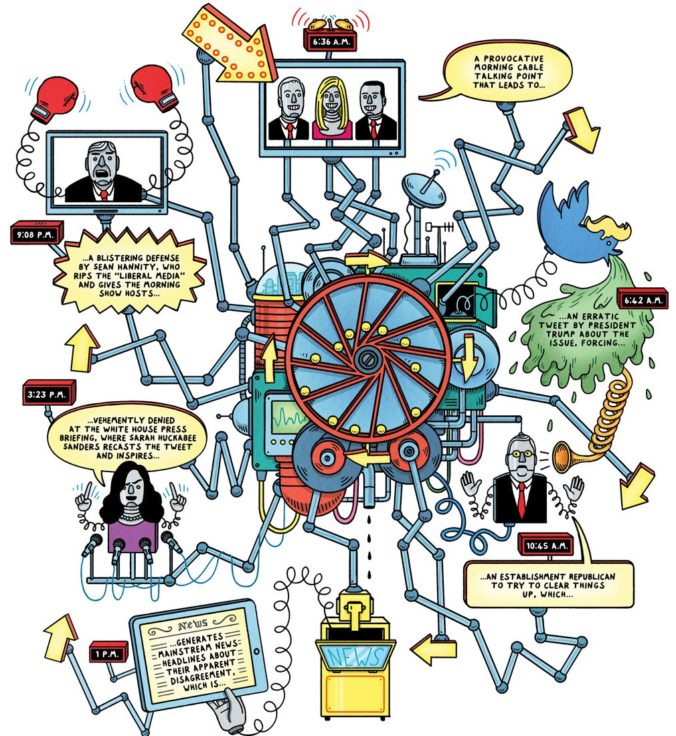

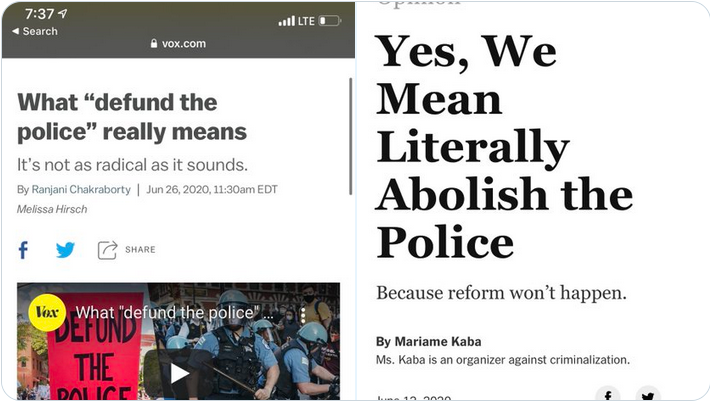

Hegel’s portrait of the purity-obsessed moralist for whom words speak louder than actions and condemnation louder than solidarity, seems to hold particular relevance for our time, in which action and judgment have blurred in virtual space.

Passages

Here are some resonant passages, followed by H. S. Harris’s paraphrases of them from Hegel’s Ladder. I’ve always been struck here by the duel between Hegel’s leaden verbiage and his sarcasm:

The self’s immediate knowing that is certain of itself is law and duty. Its intention, through being its own intention, is what is right; -all that is required is that it should know this, and should state its conviction that its knowing and willing are right.

[Conscience is what it says it is. It is not legitimate to doubt its “truthfulness.” That everyone should define himself thus, is the essence of the right. (Harris)]

Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit §§654

The spirit and substance of their association are the reciprocal assurance of their conscientiousness and good intentions, rejoicing over this mutual purity, and basking in the glory of knowing, declaring, cherishing, and fostering such an excellent state of affairs.

[This lonely service is at the same time a communal one. What the voice says is “objective,” and has universal force. To express it is to set oneself up as a pure, hence a universal, self. Everyone respects it and we all feel good for being conscientious. (Harris)]

Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit §§656

It lives in dread of besmirching the splendour of its inner being by action and an existence; and, in order to preserve the purity of its heart, it flees from contact with the actual world, and persists in its self-willed impotence to renounce its self which is reduced to the extreme of ultimate abstraction.

[It is a creative experience that loses everything, a speech that hears only its own fleeting echo. The echo cannot be identified as a return to self, because this self never leaves itself at all; it refuses to let Nature be, or to accept being for itself. It flies from the world and has its own emptiness for object; this beautiful soul is a lost soul. (Harris)]

Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit §§658

The ‘beautiful soul’, lacking an actual existence, entangled in the contradiction between its pure self and the necessity of that self to externalize itself and change itself into an actual existence, and dwelling in the immediacy of this firmly held antithesis—an immediacy which alone is the middle term reconciling the antithesis, which has been intensified to its pure abstraction, and is pure being or empty nothingness—this ‘beautiful soul’, then, being conscious of this contradiction in its unreconciled immediacy, is disordered to the point of madness, wastes itself in yearning and pines away in consumption.

[This “beautiful soul” is now stuck in its negative certainty. It must be actual, but it cannot. It can only go mad, or pine away in spiritual consumption. (Harris)]

Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit §§668

Commentary

As a summary, I’m not sure if one can do better than Jean Hyppolite’s assessment:

Above all, these beautiful souls are concerned with perceiving their inner purity and with being able to state it. Concern for themselves never completely leaves them, as true action would require.

Jean Hyppolite, Genesis and Structure of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit

And here is some commentary on the “beautiful soul” concept (as well as the closely related acting vs. judging consciousness), beginning with Judith Shklar’s incisive portrait of the beautiful soul’s hypocrisy, and ending with Robert Brandom quoting the Firesign Theatre.

The language of ethical men is that of law and convention. Pure moralism is reduced to silence in its purity and inactivity. Kantian moralism is at least not talkative. The language of conscience is that of self-worship, but it need not remain solitary. Conscience that must speak can always find some mutual admiration society whose members accept each other’s professions of good intentions and purity of purpose and this gives much pleasure to all. They share ‘the glorious privilege of knowing and expressing, of fostering and cherishing, a state altogether admirable.’ The ironist here clearly is Hegel, and not for the last time.

Hegel was very much aware of how satisfying these associations of the high-minded can be, but he could not yet guess how effectively they reinforce the self-assurance of their members and how secure a basis they offer for every conceivable bit of moralistic casuistry. He was more impressed by their instability, and to be sure, the tendency of moralizing parties and sects to disintegrate is proverbial.

There are no principles or words of unity among self- admiring consciences, even if they all approve of each other and this way of talking. ‘This general equality breaks up into the inequality of each individual existing for himself,’ because there is no way of overcoming the opposition of these individuals to other individuals or to society in general. Each one demands that he be respected, but for what? Unless there is a common standard, even if it be only common humanity, to judge actions, there is no ground for respect. The sovereignty of personal conviction renders such a yardstick impossible. Its language is therefore just an act of self-assertion. Assurances of inner righteousness, without any references to actions, are not automatically convincing. Not deeds, only inner states are offered up to be recognized. Here duty is merely a matter of words. It is a situation that has only two possibilities, evil or hypocrisy. Evil is honest and declares, ‘I do as I like.’ Hypocrisy behaves the same ways but proclaims loudly, ‘I act out of deep, inner conviction.’ Evil expects to be condemned. Hypocrisy insists on admiration. That is how conscience becomes simple selfishness…

By carefully analyzing the motives of those who act the hypocrite can easily find some selfishness lying at the root of their works. This moralistic reductionism is not only mean-spirited, it is also paralyzing. Its final success would bring a reign of pure verbiage upon us all…

Judith Shklar, Freedom and Independence

What now counts is the language in which one expresses one’s convictions. Each can say, “I assure you, I am convinced that I am doing what is right” (§§653). There is no way of gainsaying that, of determining whether the “assurance” of the “conviction” is true; each one’s “intention” is a right intention, simply because it is his own (§§654). Because there is no disputing convictions, everyone is right, and because there can be no universally valid judgment regarding either conscience or action, the only universality involved is the universal intelligibility of the language one uses in assuring others that he acts according to the conviction of his conscience (§§654)…

“Conscience” has turned into a travesty of “moral consciousness”; “good intention” has been substituted for moral goodness.

Quentin Lauer, A Reading of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit

The world may be a messy place, but one can always have a beautiful soul. The problem with beautiful souls, of course, is that they, too, substitute an aesthetic solution for a real one, and they end up in various forms of moral fanaticism. At one end of the spectrum, they are people so intent on keeping their hands clean that they never do anything; the demands of the moral life leads them to a life, paradoxically enough, of inaction. Or they can become fierce moralistic judges, ready to condemn, never ready to act themselves; or moralists who are willing to admit they make mistakes but never willing to compromise on the purity of their motives.

However, if ‘‘beautiful souls’’ are not to remain mute and simply ‘‘evaporate,’’ they must act, which means that their internal beauty and the prosaic nature of the world around them (including their own embedded selves) exists in an ineliminable tension with each other. Inevitably one form this takes is that of the judgmental moral fanatic, quick to condemn while being glacially slow to act, so worried about dirtying his hands that he can never bring them into contact with anything in the world but equally quick to point out and denounce what he sees as the stain on others’ hands. The other form it can take is that of the hyper-ironic actor, the man behind the mask, who can never be pinned down to any particular identity or action, the ‘‘free spirit’’ who is never to be identified with any action.

Terry Pinkard, in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit: A Critical Guide (ed. Moyar and Quante)

The individual who acts from conscience will look evil to others who abide by the established moral order, because he refuses to act in accordance with the duties laid down by that order; the individual will also be accused of hypocrisy, because he claims to be interested in acting morally while at the same time flouting the moral rules:

In condemning the individual conscience, the dutiful majority show themselves to be more interested in criticizing others than in acting themselves, while their accusation of hypocrisy betrays a mean-minded spirit, blind to the moral integrity of the moral individualist: ‘No man is a hero to his valet; not, however, because the man is not a hero, but because the valet – is a valet’ (PS: §665, p. 404). The moral individualist thus comes to see that its critic has much in common with itself, and that both are equally fallible: it therefore ‘confesses’ to the other, expecting the other to reciprocate. However, at first the other does not do so, remaining ‘hard hearted’: it thus itself becomes a ‘beautiful soul’, taking up a position of deranged sanctimoniousness (PS: §§668–69, pp. 406–7).

Robert Stern, Routledge Guide to Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit

What is behind the common interpretation of Hegel’s concept of the beautiful soul – it is necessary to say – is a very shopworn and stereotypical account of Romanticism, which scarcely fits historical reality. Since Hegel himself traded in these stereotypes, it is still possible that he had the Romantics in mind after all. But if that is the case, it is necessary to admit that his critique misfires entirely, directed against little more than a monster of his own making.

We need not make this assumption, however, if we consider other more likely sources for Hegel’s reflections. One of these is Book VI of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre, “The Confessions of a Beautiful Soul.” Goethe’s treatment and diagnosis of the beautiful soul anticipates Hegel’s chapter in many respects: in its suspicions about moral purity, in its criticisms of withdrawal from the world, and in its belief in the necessity of self-limitation (cf. PR §13Z). Another plausible source is Rousseau’s account of the life of the beautiful soul in Julie, or the New Heloise. There is a remarkable similarity between Hegel’s account of the beautiful soul and the main characters in Rousseau’s novel, Wolmar, Julie, and Saint-Preux. They are guided entirely by their moral feelings; they believe utterly in their moral purity; they attempt to seclude themselves from society by forming their own moral community where complete honesty and openness prevail. Last but not least, their community fails for reasons very like those Hegel discusses in the Phenomenology: they are all victims of hypocrisy.

Hypocrisy is indeed the fatal flaw of the beautiful soul. The beautiful soul retreats from the world into the life of his small community because he does not want to compromise and corrupt himself. Rousseau recommended such an experiment in living because natural sentiments, the source of all virtue, are corrupted by general society. But the problem is that, even in this small community, the beautiful soul has to compromise his moral principles. The beautiful soul wants to lead a life that is completely honest, open, and authentic, and he wants to do away with all the dishonesty, repression, and conformity of society. For this reason he chooses to live only among his friends in a secluded community. But Wolmar, Julie, and Saint-Preux constantly find that, even among themselves, they have to conceal their convictions, repress their feelings, and embellish their opinions, if they are not to offend one another or embarrass themselves. They still claim to follow principles of openness, honesty, and authenticity; but they do not comply with them in their everyday life. In other words, they are hypocrites. Thus the beautiful soul fails by its own standards. It demands honesty, openness, and authenticity; yet its hypocrisy is nothing less than self-deception.

Frederick Beiser, in Blackwell Guide to Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit (ed. Westphal)

The hard-hearted judge is doing what he originally indicted the other for. He is letting particularity affect his application of universals: applying different normative standards to doings just because they happen to be his doings…What is normatively called for—in the sense that it would be the explicit acknowledgment (what things are for the judge) of what is implicitly (in itself) going on—is a reciprocal confession. That would be the judge’s recognition of himself in the one who confessed. (As the Firesign Theatre puts it: “We’re all bozos on this bus.”)

Robert Brandom, A Spirit of Trust