Robert Musil published two large volumes of his unfinished The Man Without Qualities in his lifetime. Pseudoreality Prevails (as well as a short introduction) was published in 1930, and Into the Millennium (The Criminals) was published in 1933. He died in 1942 with nothing further published. Musil expected to live until 80 in order to finish the book, but died at age 59: the work was nowhere near completion, and since the book was a process without a foreordained end, Musil did not leave any clear plan for the book’s ending.

Genese Grill‘s new study, The World as Metaphor in Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities: Possibility as Reality, provides an invaluable structure–the best I’ve encountered–for assessing the later sections and unfinished draft material of The Man Without Qualities. Grill wrote a superb chapter in the Camden House Companion to the Works of Robert Musil on The ‘Other’ Musil: Robert Musil and Mysticism, on which this book builds.

Anyone reading The Man Without Qualities is confronted with a perplexing shift as Into the Millennium progresses. After the surgical examination of European pre-war ideologies and populations in Pseudoreality Prevails, the autopsy gradually fades after Ulrich’s sister Agathe shows up in Into the Millennium. The socio-political commentary continues, but it is broader, more comical, more inane–best represented by the increasing dominance of the crackpot Meingast (based on Ludwig Klages, a Weininger-esque self-hating Jew with anti-semitic theories). Without such formidable intellectual content to critique, Ulrich (and Musil) seek a more mystical solution to the fragmenting and dissolution of modernity.

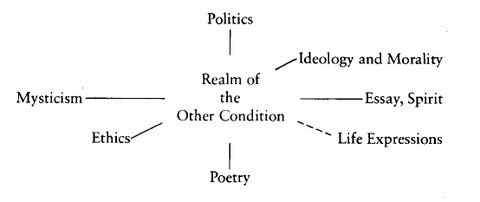

Ulrich pursues a mysterious “Other Condition” with his sister Agathe, some kind of intellectual-erotic union (consummated in the draft material) that puts the everyday world into suspension, at least briefly. It is left open whether this Other Condition is achieved or is even achievable, and its exact nature remains elusive. It’s easier to define it as what it is not: everyday reality, the political situation, bad expressionism, superficiality, irrationality, etc. This diagram from Musil’s notebooks (as translated by David Luft in Robert Musil and the Crisis of European Culture, 1880-1942) does not narrow the field:

Musil’s simultaneous training in science and the humanities drove him to accept nothing less than exactitude in even the most spiritual dimensions, hence his twin ideals of “precision and soul.” He was suspicious of both the scientific technician and the bad expressionist that reaches too easily for transcendence. He demeaned Heideggerian pseudo-Romantic attempts to proclaim spiritual superiority as Schleudermystik (“cut-rate mysticism,” more literally “centrifugal mysticism”), “whose constant preoccupation with God is at bottom exceedingly immoral” (III.46).

Grill’s major achievement is in bringing together the disparate, unpublished material of Musil’s last years into a structure that clarifies, at least somewhat, Musil’s ambitions. Because Musil dealt in abstractions and stretched them by taking little for granted, the intent still remains very open to interpretation. My disagreements below are not based on what I think Musil intended, because I don’t have a clear idea of that. Instead, they’re attempts to contextualize the material in a different way. The passages below are almost wholly those used in her book, and I’m grateful to her for highlighting them.

In essence, Grill argues that the Other Condition was a primary force behind both the book and the writing of the book, a suspension of assumptions and embrace of contingency that opened up realms of possibility not available in daily life. Grill spends a fair bit of time drawing a striking comparison between Musil’s ambition and Proust’s. Musil’s focus on introspection and subjectivity was as great as Proust’s, even though the socio-political material makes this less obvious. (Two other close peers are James Joyce and Alfred Döblin.)

But Grill also points out the strong contrast between them: while Proust left a closed structure behind to serve as a working memory palace for understanding life through art, Musil’s attitude and the state of the Other Condition mandated that no such closure occur. (Hence Musil’s one-time plan to have the novel break off in the middle of a sentence.) Hence the novel’s fragmentation into possibility and ambivalence need not be seen as a failure on any level. Such a closure would have been a betrayal of the very principles behind the novel.

Grill’s argument proceeds roughly as follows through the four chapters:

- Musil’s emphasis on circle-patterns in the later sections model the book’s rejection of linear everyday reality, embrace of contradiction and self-refutation, and a suspension of one’s attitudes to allow for a Nietzschean liberation from thoughtless conventions.

- Transgression and “crime” constitute a means of veering out of repetitive patterns of life, thought, and metaphor. Agathe and Ulrich’s union is an attempt to escape those patterns, and is representative of the Other Condition, an attempt to find a supra-moral ethics.

- Life is structured by our words and metaphors. They become ossified and stifling, and Musil saw the role of his writing as offering as much freedom from the confining strictures of our shared metaphorical life as possible.

- The idea of the “still life” is paradoxical and central, offering on the one hand a deceased frozen moment, on the other a suspension from the regular flow of life that opens up all nonextant possibilities and a aesthetically disinterested revivification of metaphor.

The intersection of metaphor and life is a theme that I have been rather preoccupied with, but I had not given much thought to Musil’s treatment of it until reading Grill’s book.

I would argue that when Grill says that “Abstraction, insofar as it is connected to universal forms, is always closer to timelessness and further from utility than representation, which is drawn from and comments upon particularities of place and moment” (32), she has muddled the issue a bit. Abstraction remains present to a far greater degree in particularities than we realize. It is obscured by the sheer reinforcement of the metaphorical structures that come to seem purely representative. Seemingly “abstract” thinking can be more liberating than the desiccated imagery of poetry precisely because it is not more abstract, but only more free:

In our poems there is too much rigid reason; the words are burned-out notions, the syntax holds out sticks and ropes as if for the blind, the meaning never gets off the ground everyone has trampled; the awakened soul cannot walk in such iron garments. (1564)

Leaving the precise, measurable, and definable sensory data out of account; all the other concepts on which we base our lives are no more than congealed metaphors [erstarren gelassene Gleichnisse]. (626)

Here Musil unites an attack on the surface beauty of most poetry with his brilliant, earlier critique of empiricism, suggesting that they both come out of an adherence to an underlying conceptual structure that is taken for granted (selbstverständlich):

The relationship between youth and empiricism seemed to him profoundly natural, and youth’s inclination to want to experience everything itself, and to expect the most surprising discoveries, moved him to see this as the philosophy appropriate to youth. But from the assertion that awaiting the rising of the sun in the east every day merely has the security of a habit, it is only a step to asserting that all human knowledge is felt only subjectively and at a particular time, or is indeed the presumption of a class or race, all of which has gradually become evident in European intellectual history. Apparently one should also add that approximately since the days of our great-grandfather’s, a new kind of individuality has made its appearance: this is the type of the empirical man or empiricist, of the person of experience who has become such a familiar open question, the person who knows how to make from a hundred of his own experiences a thousand new ones, which, however, always remain within the same circle of experience, and who has by this means created the gigantic, profitable-in-appearance monotony of the technical age. Empiricism as a philosophy might be taken as the philosophical children’s disease of this type of person. (1351)

In particulars lie generalities. As Grill puts it, “Newly experienced sensations are often all too quickly congealed into an all-too-limited circle of established beliefs” (Grill 84). This applies equally to the empiricist philosopher and the expressionist poet. Musil and Proust may speak of typologies explicitly, but they openly question them, while poets of specificity sneak the archetypes in under the guise of “representing” particulars.

Consequently, I think Grill is absolutely correct when she argues that Musil’s circular structures “suggest that all experience is metaphorical,” and that this is crucial to understanding Musil’s project. She has convinced me that Musil was as keen an observer of the contingent metaphorical structure of life as Ernst Cassirer or Hans Blumenberg.

Musil, however, also possessed a lyricism to attempt to bring out his themes in a literary fashion. For example, this passage from the “Valerie” section:

Ulrich had stumbled into the heart of the world. From there it was as far to his beloved as to the blade of grass beside his feet or to the distant tree on the sky-bare heights across the valley. Strange thought: space, the nibbling in little bites, distance distanced, replaces the warm husk and leaves behind a cadaver; but here in the heart they were no longer themselves, everything was connected with him the way the foot is no farther from the heart than the breast is. Ulrich also no longer felt that the landscape in which he was lying was outside him; nor was it within; that had dissolved or permeated everything. The sudden idea that something might happen to him while he was lying there—a wild animal, a robber, some brute—was almost impossible of accomplishment, as far away as being frightened by one’s own thoughts. / Later: Nature itself is hostile. The observer need only go into the water. / And the beloved, the person for whose sake he was experiencing all this, was no closer than some unknown traveler would have been. Sometimes his thoughts strained like eyes to imagine what they might do now, but then he gave it up again, for when he tried to approach her this way it was as if through alien territory that he imagined her in her surroundings, while he was linked to her in subterranean fashion in a quite different way. (1443)

Life is nur ein Gleichnis, except that the nur is inaccurate: Gleichnis is all we have and is far more malleable than it appears day to day. The Other Condition suspends the seeming necessity and allows for greater play (in the sense of Kant’s Third Critique) with the nominal components of existence.

Yet because the construction of the world-as-metaphor is a communal one, this is not something that can be accomplished alone. Hence the need for the union that Ulrich seeks with Agathe. I think that Grill understates the necessity for intersubjectivity in the Other Condition as conceived by Musil, the need for it to exist between people in a fundamentally communal way. I think that that is the problem that Musil is addressing in this passage, where Ulrich, writing in his diary, seems to be losing track of himself:

But I also fear that there’s a vicious circle lurking in everything that I think I have understood up to now. For I don’t want—if I now go back to my original motif—to leave the state of “significance,” and if I try to tell myself what significance is, all I come back to again and again is the state I’m in, which is that I don’t want to leave a specific state! So I don’t believe I’m looking at the truth, but what I experience is certainly not simply subjective, either; it reaches out for the truth with a thousand arms.

The Romantic posture died because the sole Romantic dreamer had nothing binding him or her to “our” world, nor even a way to pick himself or herself out once other minds were absent. For Musil, it seems, one other person might be enough. Agathe provides the needed reference point.

What of, then, the admissions of failure, such as this heartbreaking passage?

The experiment they had undertaken to shape their relationship had failed irrevocably. Vast regions of emotions and fancies that had endowed many things with a perennial splendor of unknown origin, like an opalizing sky, were now desolate. Ulrich’s mind had dried out like soil beneath which the layers that conduct the moisture that nourishes all green things had disappeared. If what he had been forced to wish for was folly—and the exhaustion with which he thought of it admitted of no doubts about that!—then what had been best in his life had always been folly: the shimmer of thinking, the breath of presumption, those tender messengers of a better home that flutter among the things of the world. Nothing remained but to become reasonable; he had to do violence to his nature and apparently submit it to a school that was not only hard but also by definition boring. He did not want to think himself born to be an idler, but would now be one if he did not soon begin to make order out of the consequences of this failure. But when he checked them over, his whole being rebelled against them, and when his being rebelled against them, he longed for Agathe; that happened without exuberance, but still as one yearns for a fellow sufferer when he is the only one with whom one can be intimate.

Grill argues, I think convincingly, that this does not make permanent the failure nor exclude a greater success. If the exploration of possibility does not encompass the imagining and inhabiting of the possibility of total and utter failure, and the accompanying despair, then the project will become complacent and rigid.

This does make for a somewhat politically and socially restricted attitude, however, and Grill explicitly states her belief that Musil’s position was one of a guardian of possibility and liberality, not as an activist or polemicist. I think this is generally true, though with slight restrictions. I do believe that Musil held fast to the worth of his method, and that while he was open to revision and modification of that method, he did not doubt the fundamental correctness of the application of reason and aesthetic disinterest to every aspect of life. That is to say, the Other Condition was to be malleable to the point of imagining total failure, but not to the point of utter self-annihilation.

And the method is more pragmatic than it is Romantic, depending on an alternating (or circular) pattern of engaging and disengaging, accepting and questioning. In a key section, Grill discusses Musil’s depiction of the two types of metaphors, “Nebel” (mist) and “Erstarren” (petrifact), and concludes:

Neither stone nor mist, therefore, is alone the true element, but rather, they work together to satisfy our shifting human instincts and desires for oscillation–oscillation between freedom and necessity, or perhaps freedom and an artificially imposed set of limitations. (Grill 69)

This is because even in the freedom of constructing new misty metaphors, the process is necessarily selective, as Grill stresses. A metaphor’s value lies not only in its highlighting connections between disparate concepts, but in leaving the possibility open for difference. It is this balance that makes a metaphor irreducible (and here the connection with Blumenberg’s metaphorology is strongest).

Now, as he realized that this failure to achieve integration had lately been apparent to him in what he called the strained relationship between.literature and reality, metaphor and truth, it flashed on Ulrich how much more all this signified than any random insight that turned up in one of those meandering conversations he had recently engaged in with the most inappropriate people. These two basic strategies, the figurative and the unequivocal, have been distinguishable ever since the beginnings of humanity. Single-mindedness is the law of all waking thought and action, as much present in a compelling logical conclusion as in the mind of the blackmailer who enforces his will on his victim step by step, and it arises from the exigencies of life where only the single-minded control of circumstances can avert disaster. Metaphor, by contrast, is like the image that fuses several meanings in a dream; it is the gliding logic of the soul, corresponding to the way things relate to each other in the intuitions of art and religion. But even what there is in life of common likes and dislikes, accord and rejection, admiration, subordination, leadership, imitation, and their opposites, the many ways man relates to himself and to nature, which are not yet and perhaps never will be purely objective, cannot be understood in other than metaphoric or figurative terms, No doubt what is called the higher humanism is only the effort to fuse together these two great halves of life, metaphor and truth, once they have been carefully distinguished from each other. But once one has distinguished everything in a metaphor that might be true from what is mere froth, one usually has gained a little truth, but at the cost of destroying the whole value of the metaphor. The extraction of the truth may have been an inescapable part of our intellectual evolution, but it has had the same·effect of boiling down a liquid to thicken it, while the really vital juices and elements escape in a cloud of steam. It is often hard, nowadays, to avoid the impression that the concepts and the rules of the moral life are only metaphors that have been boiled to death, with the revolting greasy kitchen vapors of humanism billowing around the corpses, and if a digression is permissible at this point, it can only be this, that one consequence of this impression that vaguely hovers over everything is what our era should frankly call its reverence for all that is common. For when we lie nowadays it is not so much out of weakness as out of a conviction that a man cannot prevail in life unless he is able to lie. We resort to violence because, after much long and futile talk, the simplicity of violence is an immense relief. People band together in organizations because obedience to orders enables them to do things they have long been incapable of doing out of personal conviction, and the hostility between organizations allows them to engage in the unending reciprocity of blood feuds, while love would all too soon put everyone to sleep. This has much less to do with the question of whether men are good or evil than with the fact that they have lost their sense of high and low. Another paradoxical result of this disorientation is the vulgar profusion of intellectual jewelry with which our mistrust of the intellect decks itself out. The coupling of a “philosophy” with activities that can absorb only a very small part of it, such as politics; the general obsession with turning every viewpoint into a standpoint and regarding every standpoint as a viewpoint; the need. of every kind of fanatic to keep reiterating the one idea that has ever come his way, like an image multiplied to infinity in a hall of mirrors: all these wide- spread phenomena, far from signifying a movement toward humanism, as they wish to do, in fact represent its failure, All in all, it seems that what needs to be excised from human relations is the soul that finds itself misplaced in them. The moment Ulrich realized this he felt that his life, if it had any meaning at all, demonstrated the presence of the two fundamental spheres of human existence in their separateness and in their way of working against each other. Clearly, people like himself were already being born, but they were isolated, and in his isolation he was incapable of bringing together again what had fallen apart. He had no illusions about the value of his philosophical experimentation; even if he observed the strictest logical consistency in linking thought to thought, the effect was still one of piling one ladder upon another, so that the topmost rungs teetered far above the level of natural life. He contemplated this with revulsion. (647)

This passage, Grill points out, provides a key piece of anticipatory groundwork for what Ulrich and Agathe will embark upon many hundreds of pages later. The greater emphasis on concrete political reality obscures the greater significance that Musil is juggling these concepts metaphorically in increasing degree, and that the motion toward the Other Condition is already proceeding. For illuminating the join between the earlier and latter sections of The Man Without Qualities in a way that gives real shape to the whole, Grill’s book is tremendous.