Balaustion has said that Portnoy’s Complaint is the most famous Jewish novel of the last 50 years. Is it? I think its fame may have fled. Here’s my guess as to why.

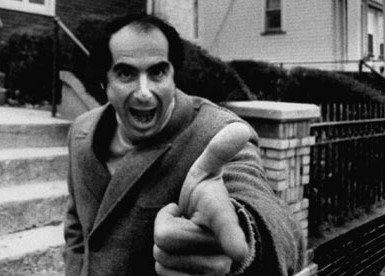

I first heard about Philip Roth when Patrimony came out, and I wasn’t interested. Then I read Woody Allen’s “The Kugelmass Episode” in high school, where a Jewish schlub enters Madame Bovary and replaces Rodolphe. He then tells the inventor that he wants to enter Portnoy’s Complaint so he can sleep with The Monkey. I asked my English teacher who or what The Monkey was. He didn’t know, but the next day he came back with the answer. He said that he didn’t think it was right that he’d left us high and dry on that question, so he’d looked it up in the library (this is pre-internet) and found the answer, which he wrote on the board: “a voracious, libidinous individual with poor cognitive function in Philip Roth’s novel Portnoy’s Complaint.” He explained that Portnoy’s Complaint was about “a very neurotic Jewish young man and his powerful right hand.”

I read the book later in high school and left it with a shrug. The Catcher in the Rye and The Fall had struck me very powerfully, while I had hated Siddhartha (to name three of those evergreen teenage books), but Portnoy was neither shocking nor obscene, just oblique. I didn’t especially enjoy it, or even grasp the nature of Portnoy’s relationship with his mother. The novel’s concerns were just too distant from mine. Here is Portnoy:

She was so deeply embedded in my consciousness that for the first year of school I seem to have believed that each of my teachers was my mother in disguise. As soon as the last bell had sounded, I would rush off for home, wondering as I ran if I could possibly make it to our apartment before she had succeeded in transforming herself. Invariably she was already in the kitchen by the time I arrived, and setting out my milk and cookies. Instead of causing me to give up my delusions, however, the feat merely intensified my respect for her powers. And then it was always a relief not to have caught her between incarnations anyway – even if I never stopped thinking; I knew that my father and sister were innocent of my mother’s real nature, and the burden of betrayal that I imagined would fall to me if I ever came upon the unawares was more than I wanted to bear at the age of five. I think I even feared that I might have to be done away with were I to catch sight of her flying in from school through the bedroom window, or making herself emerge, limb y limb, out of an invisible state and into her apron.

Yes, I can see it, but it is too overwrought! Not that such mother’s are not incredibly real, but looming over this passage and the whole book are the spectres of HaShem and the fifth commandment. A mother’s tyranny is not sufficient for this level of oppression: a whole cultural-religious apparatus must back it up. And without that force being made explicit, Portnoy’s Complaint loses its reference point in reality.

I think this must indicate a generation gap between those who read Portnoy in the 60s and 70s and those of us who read it today. Not that many people do. As far as Jewish novels go, Herzog is better known among my contemporaries (Malamud has fallen off the map completely).

So while it’s a bit further back, I consider the most important Jewish novel of recent decades to be The Catcher in the Rye. Immediate objection: “It’s not about Judaism! It’s not even about a Jew!” Yes, and I think that’s what makes it so lasting and significant. I pick it with intentional irony because its Judaism is not explicit, Salinger having migrated to some cryptic Buddhism years earlier. Outside of strictly devotional circles, I think that this is American Jewish cultural and literary legacy outside of strictly religious circles: a divestment of a very particular religious and ethical baggage.

This, I think, was a product of the efforts of Roth’s generation and the one or two surrounding generations to emancipate the next generation from their neuroses and from their pasts. Many of them (including Salinger’s father) married Gentiles ; many of them raised their kids as atheists. I’m reminded of a story that philosopher Rebecca Kukla told: “My parents explained to me when I was six – when I came home from school asking if it was true that I was Jewish and what that word meant – that being Jewish meant being a Marxist and an atheist.”

There are a lot of complex issues here surrounding assimilation, secularization, and cultural identity. Without getting into their innards, the outside view still seems to point in one direction: a movement away from the mid-century forms of Jewish consciousness that Roth, Bellow, Malamud, Ozick, and others chronicle. Whatever the motivations and whatever the tactics, the end result was to yield younger generations that would not be bound to that consciousness.

From my experience and the experiences of others I’ve known, those generations succeeded in immense measure. Certain stereotypical neuroses remain, but very rarely in the maniacally oppressive guilt-ridden forms that Roth portrays. It seems that my generation was freed to worry only about the Holocaust rather than about the Holocaust and masturbation both. I think that the Coen Brothers’ A Serious Man captures this transition as well as anything. The world is still cruel, frightening, and arbitrary, but it didn’t need to be seen through the prism of the Old Testament. We youths are free to adopt as many unhelpful interpretive frames as we want. (This is precisely the story of The Catcher in the Rye.)

The consequence, however, is that Portnoy’s Complaint has dated poorly and does not mean to my generation what it meant to Roth’s. We were emancipated from its concerns as well as its context. “LET’S PUT THE ID BACK IN YID!” says Portnoy. Well, they did, not for themselves, but for their children. But as a consequence it’s hard for us to feel what all the fuss was about.

Here’s a parallel: the then-edgy humor of Harvey Kurtzman, Stan Freberg, and Allan Sherman–conflicted but basically conservative sorts who liked deflating pompous asses and having a laugh, but didn’t like the looks of those hippies–no longer resonates, while the Marx Brothers, early Woody Allen, and the Honeymooners still do, all based on enduring trends of absurdity and slapstick that were less vulnerable to the shifting degrees of societal acceptability. (It was always bizarre to find out how much acceptance these counterculture court jesters had had even at the time, sort of like finding out Shel Silverstein was a permanent fixture at the Playboy Mansion.) The legacy of Kurtzman and Freberg produced Laugh-In, Mad Magazine, Weird Al Yankovic, and the perennial face of excruciating parodic irrelevance, Saturday Night Live. (As a child, I knew instinctively that SCTV, produced in a hothouse of free association with neither provocation nor egomania, was by far the better show.)

So Portnoy’s Complaint screams out from a psychological place that no longer exists. American Pastoral unfortunately reveals the degree to which the next generation was emancipated: the portrait of Weatherman-cum-Jainist Merry is so shallow and unconvincing as to hollow out the whole book. Roth has no idea what he’s talking about. American Pastoral won the Pulitzer because the judges lacked the expertise to realize that the portrait of Merry was a failure, and so assumed, wrongly, that the character was convincing. On the other hand, I assume that Portnoy’s Complaint is quite authentic, yet I cannot verify its authenticity. The substrate has dissolved.

In turn, Sabbath’s Theater succeeds perhaps better than any other Roth novel because its main character realizes he is an anachronism, a dirty old man unable to confront or escape his cultural baggage. Such self-indicting self-parody could only be written once, and Roth’s subsequent work has left me absolutely cold.

What did get passed on was a secularized version of the Ashkenazi, immigrant culture which no longer served as an ethical and spiritual straitjacket. The concrete specifics of the culture, as chronicled vividly by Malamud, did not survive, but a background of intellectual, cultural, and social sensibilities persisted, and you can still detect them in a lot of American science-fiction, stand-up comedy, and quite a few other genres. Roth’s generation was very much transitional, alienated from both their foreign ancestors and their native children, so trapped by the former that they were unwilling (or unable) to trap the latter. So Portnoy’s Complaint is less a monument than a faded snapshot. The Catcher in the Rye was prophecy.