I never thought I’d get the chance to see Partch’s Delusion of the Fury. The Japan Society’s production is the first since the premiere almost 40 years ago, and I get the feeling there’s not going to be another one anytime soon, since Partch wrote for his own unwieldy instruments and the requirements he placed on performers were rather strenuous. (Partch’s recommendation that his instruments be wheeled around on the stage during the performance, adding to their “corporeality,” was dropped in this production.) So I consider myself blessed to have the experience of getting some idea of what Partch had in mind, even if his full intentions were probably unrealizable. Partch was something of a magpie in stealing bits and pieces from other cultures–gamelan here, gagaku there–but the synthesis is so intensely personal as to be an unrecognizable miscegenation. His vaunted excursions into microtones are only a small part of Partch’s outre gestalt.

I never thought I’d get the chance to see Partch’s Delusion of the Fury. The Japan Society’s production is the first since the premiere almost 40 years ago, and I get the feeling there’s not going to be another one anytime soon, since Partch wrote for his own unwieldy instruments and the requirements he placed on performers were rather strenuous. (Partch’s recommendation that his instruments be wheeled around on the stage during the performance, adding to their “corporeality,” was dropped in this production.) So I consider myself blessed to have the experience of getting some idea of what Partch had in mind, even if his full intentions were probably unrealizable. Partch was something of a magpie in stealing bits and pieces from other cultures–gamelan here, gagaku there–but the synthesis is so intensely personal as to be an unrecognizable miscegenation. His vaunted excursions into microtones are only a small part of Partch’s outre gestalt.

It’s because of the private nature of the work that I can’t easily assess my own reaction to it difficult. Partch may have thought that he was tapping into some universal mythos and music, but I have to say that at least in that regard, he failed. All of his work, and Delusion is perhaps the most fully realized work but not any more or less accessible than the others, springs from his willfully cultivated outsider status and mostly solitary development of his own musical theories and dogma. Partch was far from untrained, but he was not a social man, and it seems that estrangement came to him naturally, particularly from “The Establishment” and high culture in general. There are a number of other American composers that fall into this category, and they rank among the best the country has produced: Conlon Nancarrow, Henry Cowell, Carl Ruggles, Edgard Varese (not actually American, but tried his damnedest to be), Sun Ra, Lou Harrison, Cecil Taylor, and Anthony Braxton. All of them resisted (and continue to resist) easy assimilation into a larger historical context, and many actively tried to divorce themselves from being associated with any larger movement. (I do not think it’s a coincidence that many of them, including Partch, also happened to be queer, but that’s all I’m prepared to say on that subject. See also Percy Grainger, who ironically was too establishment to make the list.) Partch, himself quite the curmudgeon, extended this autonomy to the very instruments themselves, ensuring himself an even greater degree of personal control over performance. The resultant effect, no doubt intentional, is that there is more work to be done to get inside the corpus of these composers than those who exist closer to the mainstream horizon of recent times.

So here’s the plot, in Partch’s words:

It is an olden time, but neither a precise time nor a precise place. The “Exordium” is an overture, and invocation, the beginning of a ritualistic web. Act I, on the recurrent theme of Noh plays, is a music-theater portrayal of release from the wheel of life and death. It opens with a pilgrim in search of a particular shrine, where he may do penance for murder. The murdered man appears as a ghost, sees first the assassin, then his young son looking for a vision of his father’s face. Spurred to resentment by his son’s presence, he lives again through the ordeal of death, but at the end — with the supplication “Pray for me!” — he finds reconciliation.

There is nowhere, from the beginning of the “Exordium” to the end of Act II, a complete cessation of music. The “Sanctus” ties Acts I and II together; it is the Epilogue to the one, the Prologue to the other. Act II involves a reconciliation with life. A young vagabond is cooking a meal over a fire in rocks when an old woman approaches, searching for a lost kid. She finds the kid, but — due to a misunderstanding caused by the hobo’s deafness — a dispute ensues. Villagers gather and, during a violent dance, fore the quarreling couple to appear before the justice of the peace, who is both deaf and nearsighted.

Following the judge’s sentence, the Chorus sings in unison, “Oh, how did we ever get by without justice?” and a voice offstage reverts to the supplication at the end of Act I.

The near-total lack of narration and speech (partly for copyright reasons, apparently) does not make it easy to understand what is going on without the accompanying program notes, and the partial doubling of the actors in the main roles in the two parts is more puzzling than anything else. To the extent that Delusion reaches for universality, it is to a totality of musical performance. Watching it, I could only feel that narrative and thematic drive had been subordinated to the physical performance of music (and dance) itself, which struggled under the heavy responsibility of evoking those very traits. There’s a hint of this in Partch’s own description of his aesthetics:

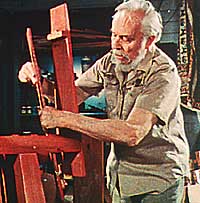

The work that I have been doing these many years parallels much in the attitudes and actions of primitive man. He found sound-magic in the common materials around him. He then proceeded to make the vehicle, the instrument, as visually beautiful as he could. Finally, he involved the sound-magic and the visual beauty in his everyday words and experiences, his ritual and drama, in order to lend greater meaning to his life. This is my trinity: sound-magic, visual beauty, experience-ritual.

Where one might expect narrative, there is only raw experience and ritual, which I gather Partch intended to place in a prior and more fundamental place than what constitutes modern storytelling. The Residents, hugely influenced by Partch, drew upon this aspect in their own early work, particularly in the nonsense narrative of Not Available and the instrumental “narratives” of Eskimo and above all “Six Things to a Cycle” (off of Fingerprince), which is so Partch-like as to constitute a tribute. The plot: “Man, represented as a primitive humanoid, is consumed by his self-created environment only to be replaced by a new creature, still primitive, still faulty, but destined to rule the world just as poorly.” Its (entire) lyrics?

Chew chew GUM chew GUM GUM chew chew

Chew chew GUM chew GUM GUM chew chew

Chew chew GUM chew GUM GUM chew chew

[Smack Smack Smack]

So yeah, I think that says it all.