In this chaotic, surreal, and trying year, books as always provided a source of steadiness and continuity, when there was enough time and space to give them full attention.

My two books of the year are both superior anthologies suffused with the editor/translators’ love and reverence for their authors–inspiring feats in themselves. The third volume of Musil translated by Genese Grill and published by Contra Mundum is a massive and masterful anthology of Musil’s plays and theater writings, the most substantial new Musil volume in years, expertly rendered and annotated. Hannes Bajohr, Florian Fuchs, and Joe Paul Kroll collectively perform an even greater feat in drawing together Blumenberg’s essays across the breadth of his career and finally producing an approachable entry point to his work in English. The introductions to both volumes are superb. The works are old, but Grill, Bajohr, Fuchs, and Kroll are their animating spirits today.

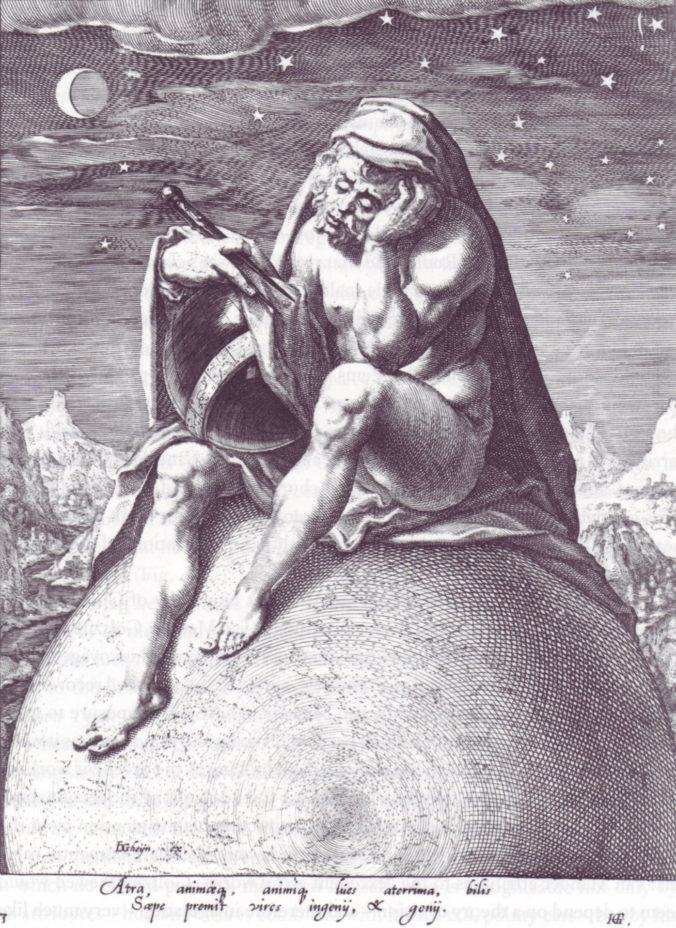

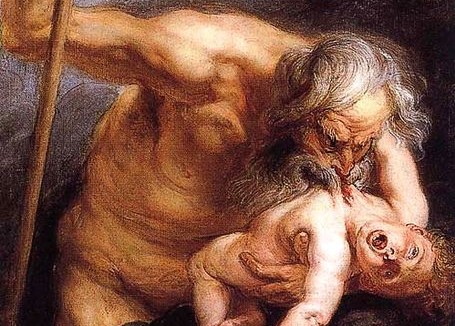

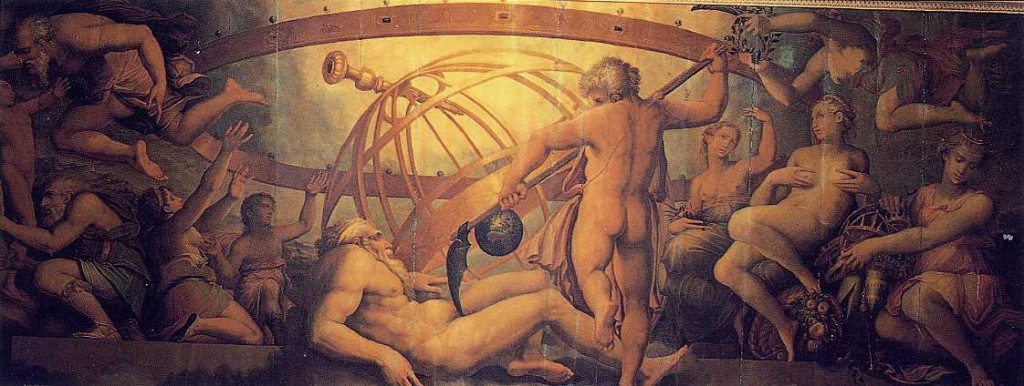

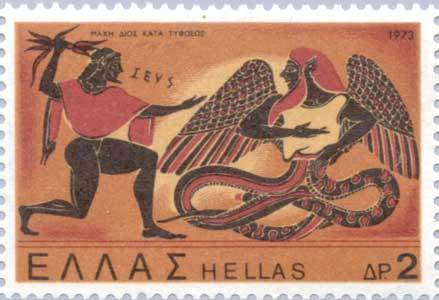

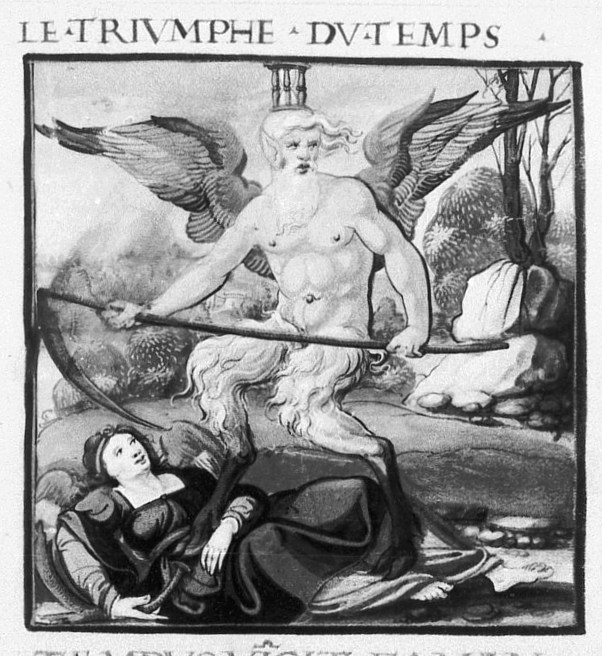

The same goes for Steve G. Lofts’s new translation of Ernst Cassirer’s Philosophy of Symbolic Forms, a massive undertaking of an underappreciated work by an underappreciated philosopher, the third Davos participant who saw more widely than Carnap and more humanely than Heidegger. A more affordable edition is warranted. And the long-awaited reissue of Klibansky, Panofsky, and Saxl’s Saturn and Melancholy, done with immense care and comprehensiveness, is a model example of cultural history at a level of depth and intimacy that has always been rare, and is perhaps becoming rarer.

Fantagraphics’s reissues of Alberto Breccia’s stunning work also deserve more attention. I read part of Perramus when Fantagraphics issued it 30 years ago and was blown away by Breccia’s singular style; its’ good to have the whole thing finally. His version of The Eternaut is also remarkable.

I hesitate to mention too many other books for fear of neglecting the others, but I will say that of the science and technology books, several deal with subjects that are currently inundated with popularizations. In my eye, those below are notably superior to the rest of their crowd, though the marketplace of ideas has apparently and frustratingly failed to raise these books above their brethren. To a lesser extent, the same applies to history and politics.

Jacob Burckhardt said that the 20th century would be the age of oversimplification. The 21st has so far been the age of increasingly desperate and defensive oversimplification, across all domains of knowledge. Here’s to the fight against it.

(Final note: for an anthology of short plague-related stories, please check out my little project The Enneadecameron, featuring worthy tales by John Crowley, Irina Dumitrescu, Genese Grill, Alta Ifland, and many more.)

BOOKS OF THE YEAR

Theater Symptoms: Plays and Writings on Drama

Musil, Robert (Author), Grill, Genese (Translator), Grill, Genese (Introduction)

Contra Mundum Press

History, Metaphors, Fables: A Hans Blumenberg Reader (signale|TRANSFER: German Thought in Translation)

Blumenberg, Hans (Author), Bajohr, Hannes (Translator), Fuchs, Florian (Translator), Kroll, Joe Paul (Translator)

Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library

LITERATURE

Eros, Unbroken

Kim, Annie (Author)

Word Works

The Long White Cloud of Unknowing

Samuels, Lisa (Author)

Chax Press

The Bern Book: A Record of a Voyage of the Mind (American Literature)

Carter, Vincent O. (Author), McCarthy, Jesse (Introduction)

Dalkey Archive Press

Peach Blossom Paradise (New York Review Books Classics)

Fei, Ge (Author), Morse, Canaan (Translator)

NYRB Classics

Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk: Selected Stories of Nikolai Leskov (New York Review Books Classics)

Leskov, Nikolai (Author), Chandler, Robert (Translator), Rayfield, Donald (Translator), Edgerton, William (Translator), Rayfield, Donald (Introduction)

NYRB Classics

Alexandria: A Novel

Kingsnorth, Paul (Author)

Graywolf Press

Impostures (Library of Arabic Literature, 65)

al-Ḥarīrī (Author), Cooperson, Michael (Translator), Kilito, Abdelfattah (Foreword)

NYU Press

Rogomelec (The Envelope-silence, 6)

Fini, Leonor (Author), Skwersky, Serena Shanken (Translator), Kulik, William T. (Translator), Eburne, Jonathan P. (Introduction)

Wakefield Press

Meaning a Life: an Autobiography

Oppen, Mary (Author), Yang, Jeffrey (Introduction)

New Directions

The Lost Writings

Kafka, Franz (Author), Stach, Reiner (Editor), Hofmann, Michael (Translator)

New Directions

Collected Stories

Hazzard, Shirley (Author), Olubas, Brigitta (Editor), Heller, Zoë (Foreword)

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Surviving: Stories, Essays, Interviews (New York Review Books Classics)

Green, Henry (Author), Yorke, Matthew (Editor), Updike, John (Introduction), Yorke, Sebastian (Afterword)

NYRB Classics

The Homeric Hymn to Hermes (Cambridge Classical Texts and Commentaries, Series Number 62)

Thomas, Oliver (Editor)

Cambridge University Press

Lame Fate | Ugly Swans (36) (Rediscovered Classics)

Strugatsky, Arkady (Author), Strugatsky, Boris (Author), Strugatsky, Boris (Author), Vinokour, Maya (Author)

Chicago Review Press

The Third Walpurgis Night: The Complete Text (The Margellos World Republic of Letters)

Kraus, Karl (Author), Bridgham, Fred (Translator), Timms, Edward (Translator), Perloff, Marjorie (Foreword)

Yale University Press

Death in Her Hands: A Novel

Moshfegh, Ottessa (Author)

Penguin Press

I Live in the Slums: Stories (The Margellos World Republic of Letters)

Can Xue (Author), Gernant, Karen (Translator), Chen, Zeping (Translator)

Yale University Press

Other Moons: Vietnamese Short Stories of the American War and Its Aftermath

Ha, Quan Manh (Translator), Babcock, Joseph (Translator)

Columbia University Press

Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow (Russian Library)

Radishchev, Alexander (Author), Reyfman, Irina (Translator), Kahn, Andrew (Translator)

Columbia University Press

A Lover's Discourse

Guo, Xiaolu (Author), Guo, Xiaolu (Author), Guo, Xiaolu (Author)

Grove Press

The Selected Poems of Tu Fu: Expanded and Newly Translated by David Hinton

Fu, Tu (Author), Hinton, David (Translator)

New Directions

Instantiation

Egan, Greg (Author)

Greg Egan

The Evidence

Priest, Christopher (Author)

Gollancz

Piranesi

Clarke, Susanna (Author)

Bloomsbury Publishing

Dispersion

Egan, Greg (Author)

Subterranean Pr

Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas: A Novel

de Assis, Joaquim Maria Machado (Author), Costa, Margaret Jull (Translator), Patterson, Robin (Translator)

Liveright

HUMANITIES

Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion, and Art

Klibansky, Raymond (Author), Panofsky, Erwin (Author), Saxl, Fritz (Author), Despoix, Philippe (Editor), Leroux, Georges (Editor)

McGill-Queen's University Press

Michelangelo’s Design Principles, Particularly in Relation to Those of Raphael

Panofsky, Erwin (Author), Panofsky-Soergel, Gerda (Editor), Spooner, Joseph (Translator), Panofsky-Soergel, Gerda (Introduction)

Princeton University Press

The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms, Volume 1: Language

Cassirer, Ernst (Author), Gordon, Peter E. (Foreword)

Routledge

The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms, Volume 2: Mythical Thinking

Cassirer, Ernst (Author), Gordon, Peter E. (Foreword)

Routledge

The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms, Volume 3: Phenomenology of Cognition

Cassirer, Ernst (Author), Gordon, Peter E. (Foreword), Lofts, Steve G. (Translator)

Routledge

Inky Fingers: The Making of Books in Early Modern Europe

Grafton, Anthony (Author)

Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press

Hittite Texts and Greek Religion: Contact, Interaction, and Comparison

Rutherford, Ian (Author)

OUP Oxford

A Companion to Ancient Greek and Roman Music (Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World)

Lynch, Tosca A. C. (Editor), Rocconi, Eleonora (Editor)

Wiley-Blackwell

Wisdom as a Way of Life: Theravāda Buddhism Reimagined

Collins, Steven (Author), McDaniel, Justin (Editor), Hallisey, Charles (Introduction)

Columbia University Press

Time in Ancient Stories of Origin

Walter, Anke (Author)

OUP Oxford

Anger: The Conflicted History of an Emotion (Vices and Virtues)

Rosenwein, Barbara H. (Author)

Yale University Press

Who Needs a World View?

Geuss, Raymond (Author)

Harvard University Press

Civilization and the Culture of Science: Science and the Shaping of Modernity, 1795-1935

Gaukroger, Stephen (Author)

Oxford University Press

How to Think like Shakespeare: Lessons from a Renaissance Education (Skills for Scholars)

Newstok, Scott (Author)

Princeton University Press

Comparing the Literatures: Literary Studies in a Global Age

Damrosch, David (Author)

Princeton University Press

Classical Indian Philosophy: A history of philosophy without any gaps, Volume 5

Adamson, Peter (Author), Ganeri, Jonardon (Author)

Oxford University Press

The Emergence of Subjectivity in the Ancient and Medieval World: An Interpretation of Western Civilization

Stewart, Jon (Author)

Oxford University Press

Have A Bleedin Guess: The Story of Hex Enduction Hour

Hanley, Paul (Author)

Route

Frank Ramsey: A Sheer Excess of Powers

Misak, Cheryl (Author)

Oxford University Press

Early Modern German Philosophy (1690-1750)

Dyck, Corey W. (Author)

Oxford University Press

Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture

Harvey, Eleanor Jones (Author), Sues, Hans-Dieter (Preface)

Princeton University Press

The Enlightenment that Failed: Ideas, Revolution, and Democratic Defeat, 1748-1830

Israel, Jonathan I. (Author)

Oxford University Press

Rediscovering the Islamic Classics: How Editors and Print Culture Transformed an Intellectual Tradition

El Shamsy, Ahmed (Author)

Princeton University Press

The Origins of Philosophy in Ancient Greece and Ancient India: A Historical Comparison

Seaford, Richard (Author)

Cambridge University Press

SCIENCE & TECH

The Light Ages: The Surprising Story of Medieval Science

Falk, Seb (Author)

W. W. Norton & Company

Predict and Surveil: Data, Discretion, and the Future of Policing

Brayne, Sarah (Author)

Oxford University Press

How the Brain Makes Decisions

Boraud, Thomas (Author)

Oxford University Press

Every Life Is on Fire: How Thermodynamics Explains the Origins of Living Things

England, Jeremy (Author)

Basic Books

The Phantom Pattern Problem: The Mirage of Big Data

Smith, Gary (Author), Cordes, Jay (Author)

Oxford University Press

Metazoa: Animal Life and the Birth of the Mind

Godfrey-Smith, Peter (Author)

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

A Dominant Character: How J. B. S. Haldane Transformed Genetics, Became a Communist, and Risked His Neck for Science: The Radical Science and Restless Politics of J. B. S. Haldane

Subramanian, Samanth (Author)

W. W. Norton & Company

Darwin's Psychology: The Theatre of Agency

Bradley, Ben (Author)

OUP Oxford

The Art of Doing Science and Engineering: Learning to Learn

Richard W. Hamming (Author), Bret Victor (Foreword)

Stripe Press

HISTORY

Rescue the Surviving Souls: The Great Jewish Refugee Crisis of the Seventeenth Century

Teller, Adam (Author)

Princeton University Press

Virtue Politics: Soulcraft and Statecraft in Renaissance Italy

Hankins, James (Author)

Belknap Press

The Invention of China

Hayton, Bill (Author)

Yale University Press

China’s Good War: How World War II Is Shaping a New Nationalism

Mitter, Rana (Author)

Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press

Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe

Herrin, Judith (Author)

Princeton University Press

Blood Royal: Dynastic Politics in Medieval Europe (The James Lydon Lectures in Medieval History and Culture)

Bartlett, Robert (Author)

Cambridge University Press

Legions of Pigs in the Early Medieval West (Yale Agrarian Studies Series)

Kreiner, Jamie (Author)

Yale University Press

Superpower Interrupted: The Chinese History of the World

Schuman, Michael (Author)

PublicAffairs

Away from Chaos: The Middle East and the Challenge to the West

Kepel, Gilles (Author), Randolph, Henry (Translator)

Columbia University Press

Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare

Rid, Thomas (Author)

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Illuminating History: A Retrospective of Seven Decades

Bailyn, Bernard (Author)

W. W. Norton & Company

The Human Factor: Gorbachev, Reagan, and Thatcher, and the End of the Cold War

Brown, Archie (Author)

Oxford University Press

Has China Won?: The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy

Mahbubani, Kishore (Author)

PublicAffairs

The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History

Mikaberidze, Alexander (Author)

Oxford University Press

SOCIAL SCIENCES

France before 1789: The Unraveling of an Absolutist Regime

Elster, Jon (Author)

Princeton University Press

The Blind Storyteller: How We Reason About Human Nature

Berent, Iris (Author)

Oxford University Press

What’s Wrong with Economics?: A Primer for the Perplexed

Skidelsky, Robert (Author)

Yale University Press

COMICS AND ART

The Eternaut 1969 (The Alberto Breccia Library)

German Oesterheld, Hector (Author), Breccia, Alberto (Artist)

Fantagraphics Books

Perramus: The City and Oblivion (The Alberto Breccia Library)

Breccia, Alberto (Author), Sasturain, Juan (Author), Mena, Erica (Translator)

Fantagraphics

The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud

Tsurita, Kuniko (Author), Holmberg, Ryan (Translator)

Drawn and Quarterly

Nymph

Marzocchi, Leila (Author), Marzocchi, Leila (Artist)

Fantagraphics Books

Stay

Trondheim, Lewis (Author), Chevillard, Hubert (Artist)

Magnetic Press

Infinity 8 Vol.7: All for Nothing (INFINITY 8 HC)

Trondheim, Lewis (Author), Boulet (Author), Kennedy, Mike (Editor), Boulet (Artist)

Magnetic Press

Infinity 8 vol.8: Until the End (INFINITY 8 HC)

Trondheim, Lewis (Author), Killoffer (Artist)

Magnetic Press

Barnaby Volume Four (BARNABY HC)

Johnson, Crockett (Author), Nel, Philip (Series Editor), Robbins, Trina (Introduction), Clowes, Daniel (Cover Art)

Fantagraphics Books

Pogo: The Complete Syndicated Comic Strips Vols. 5 & 6 Boxed Set (POGO COMP SYNDICATED STRIPS HC BOX SET)

Kelly, Walt (Author), Kelly, Walt (Artist)

Fantagraphics Books

Winter Warrior: A Vietnam Vet's Anti-War Odyssey

Gilbert, Eve (Author), Camil, Scott (Author)

Fantagraphics

The George Herriman Library: Krazy & Ignatz 1919-1921 (GEORGE HERRIMAN LIBRARY HC)

Herriman, George (Author), Herriman, George (Artist)

Fantagraphics Books

The Dairy Restaurant (Jewish Encounters Series)

Katchor, Ben (Author)

Pantheon

The Daughters of Ys

Anderson, M. T. (Author), Rioux, Jo (Illustrator)

First Second

Philip Guston: A Life Spent Painting

Storr, Robert (Author)

Laurence King Publishing

Philip Guston Now

Guston, Philip (Artist), Cooper, Harry (Contributor), Godfrey, Mark (Contributor), Greene, Alison de Lima (Contributor), Nesin, Kate (Contributor), Fischli, Peter (Contributor), Hancock, Trenton Doyle (Contributor), Kentridge, William (Contributor), Dean, Tacita (Contributor), Ligon, Glenn (Contributor), Roberts, Jennifer (Contributor)

D.A.P./National Gallery of Art

Year of the Rabbit

Veasna, Tian (Author), Dascher, Helge (Translator)

Drawn and Quarterly

The Phantom Twin

Brown, Lisa (Author)

First Second

Solutions and Other Problems

Brosh, Allie (Author)

Gallery Books

Stuck Rubber Baby 25th Anniversary Edition

Cruse, Howard (Author), Bechdel, Alison (Introduction)

First Second

Paying the Land

Sacco, Joe (Author)

Metropolitan Books

Albrecht Dürer

Metzger, Christof (Editor)

Prestel

Glass Town: The Imaginary World of the Brontës

Greenberg, Isabel (Author)

Harry N. Abrams

Anselm Kiefer in Conversation with Klaus Dermutz (The German List)

Kiefer, Anselm (Author), Dermutz, Klaus (Author), Lewis, Tess (Translator)

Seagull Books

Exploring the Invisible: Art, Science, and the Spiritual – Revised and Expanded Edition

Gamwell, Lynn (Author), Tyson, Neil deGrasse (Foreword)

Princeton University Press