From The Comics Journal’s interview of David B.:

WIVEL: Why is occultism so fascinating to you, compared to other belief systems?

DAVID B: Because it alludes to another dimension, another possibility. That is to say that there are things that are hidden, a hidden dimension. And that’s exactly what was going on with my brother’s illness. One moment he’d seem normal, and then suddenly there would be a seizure that made him fall to the ground. So by necessity, in order to understand the discrepancy between these two states, which constituted my brother’s reality, I tried to find the explanation in something that was within my frame of reference. I found it in occultism, more so than in clinical reality, because anyway, the physicians were incapable of curing him — so I had to go elsewhere. That’s what my parents did too, in taking macrobiotics, tracking down gurus, all that stuff. The reality had to be elsewhere. That’s also why, when I was little, I’d invent friends who were fantastical characters. Children often make up imaginary friends who are friendly, such as heroes, but for me they were ghosts and demons, because that was my frame of reference. I needed friends who existed within that context. My brother’s illness threw us into an alternate reality, and that was a problem for society around us, with which we had no way of reasoning, because my brother couldn’t get any better. I’d accepted the fact that this was our context and we had to live in it, so we were on the side of the demons, on the side of mystery, on the side of night. It was a life choice.

From the point I realized that my brother would never be cured; we had to embrace it, we had to accept it. Because society rejected us — when we played in the streets with our friends and my brother would have a seizure, what we experienced was instantaneous, total rejection. After a while, my friends’ parents would come see my parents and tell them they shouldn’t let their son outside and that they ought to put him “somewhere,” and so on. We were perforce in our own world, so we were rejected. In some ways, being a kid, I found that much more captivating than reality. It was something good. Later on it was hard, I came to understand that it had cut me off from a lot of things. Anyway, there was pain.

WIVEL: It was a way of surviving.

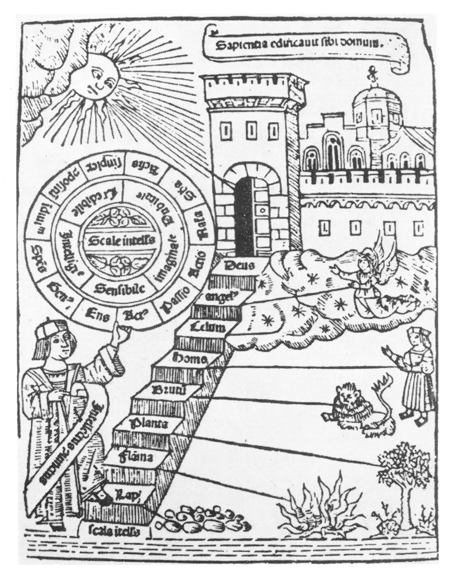

DAVID B: Yes, it was a way of sectioning off my life, of understanding where I was, and also of breaking open my imagination. Since I was already drawing a lot anyway, esoterism provided an inexhaustible trove of images, a very rich and interesting one — the alchemic engravings and all that stuff is something that you never get tired of looking at. It’s not necessarily that you get attached to the ideas behind them — it’s more the shock of the image, the poetic shock of seeing this object where there’s a whole bunch of stuff — a fish flying in the sky, next to a cube, over an ocean where there’s a guy who is drowning. You see? Hey, it’s almost a comic-book panel! There’s a story to it. When someone explains to you what it means, that’s cool too, but at the time I didn’t understand a word of it — it was the poetic shock of the image, the graphic shock that transported me. It was extraordinary! I’d feel little surges of adrenaline when I looked at that, and as a matter of fact, I felt as if I was physically touching the problem that affected our family, the problem that affected my brother. And I’d say, “My brother’s in there, within that mystery.”

WIVEL: And the intellectual side of all this only came later?

DAVID B: The intellectual side came later, when I grew up. I acquired knowledge to the point where I no longer was only interested in the images, but also in the texts that accompanied them. The explanations. It’s also from that point on, the moment you grow up, that the pain manifests itself. In a certain sense you’re innocent when you’re a child. You find simple solutions, very comforting ones. The pain comes the moment you try to explain and understand things — that’s when the pain turns fierce.

WIVEL: Occultism is a way of explaining the unknown, like religion — what is the difference between the two?

DAVID B: I am in no sense a believer. I don’t believe in anything at all, but there’s probably something to it, the area of belief — that much is certain. We all need to build ourselves a little personal religion or belief. The fascination with occultism springs from that, but to what degree I’m not exactly sure. Anyway, it doesn’t matter. I’m not trying to analyze it — in fact, it’s a way of constructing your own “mise en scène.” Like religious people with their holidays and religious ceremonies. I needed to mount my own ceremonies and build up my own symbolism — and it’s also there in the graphic work in Epileptic.

WIVEL: And you’ll keep on exploring it in Nocturnal Incidents [Les Incidents de la nuit]?

DAVID B: Absolutely, that’s really the theme of Nocturnal Incidents — my love of books and my love of images, my love of paper and all of that.

WIVEL: And also in your albums for the big publishers, which contain all of that, but…

DAVID B: Yes, there’s the album I did for Dupuis, Reading the Ruins [La Lecture de ruines], that’s exactly right. It concerns a mad scientist. He’s been driven crazy by the war, and he’s trying to understand what war is. He believes that war is a piece of writing and it must be read — the ruins are letters and can be read. And that’s exactly the work I did through esoterism, assimilating it with what I was thinking in terms of my brother’s illness. When my brother would speak or when he’d have a seizure, there was something to read in that. I saw this war and that’s why I drew so many battles. To me that represented my brother’s seizures — that’s self-evident. When my brother would have a seizure, there was a battle taking place within his body — two armies confronting each other and throwing him out of balance. That’s Reading the Ruins.