Installment two of my books of the year, with most nonfiction still to come. It seemed a very lean year for comics overall. The big event is the long-delayed translation of the first half of Lewis Trondheim’s Ralph Azham, his 600-page treatment of power, politics, religion, and family. Trondheim’s ability to improvise a better story than most people can plan out remains exceptional. There is also the final book of Hubert’s uncompleted The Ogre Gods, putting a point on his loss through suicide.

Ralph Azham #1: Black Are The Stars (1)

Trondheim, Lewis (Author)

Papercutz

Ralph Azham #2: The Land of the Blue Demons (2)

Trondheim, Lewis (Author)

Papercutz

First Born: The Ogre Gods Book Four (OGRE GODS HC)

Hubert (Author), Gatignol, Bertrand (Artist)

Magnetic Press

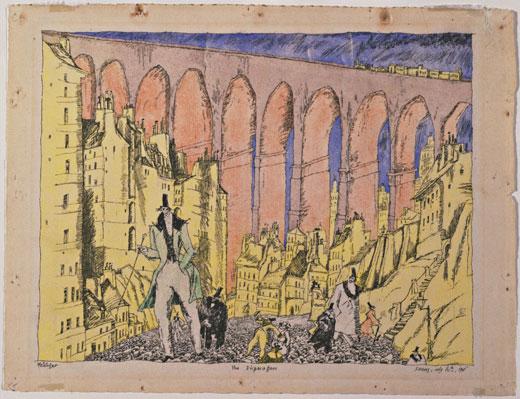

La Synagogue

Sfar Joann (Author), Sfar Joann (Illustrator)

DARGAUD

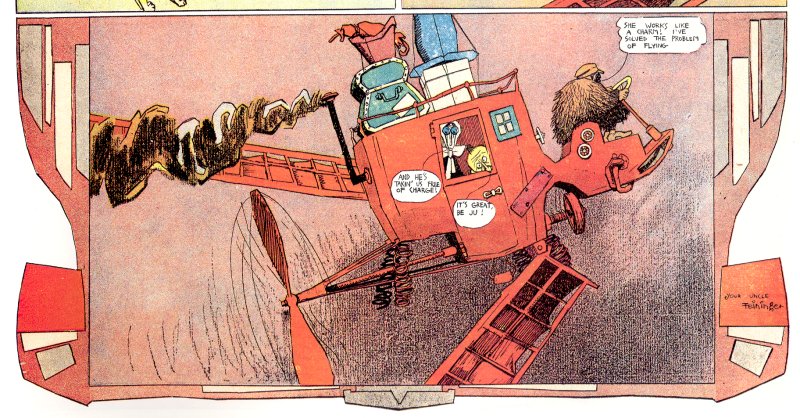

Dungeon: Early Years, vol. 3: Wihout a Sound (3)

Gaultier, Christophe (Author), Sfar, Joann (Author), Trondheim, Lewis (Author), Oiry, Stephane (Author)

NBM Publishing

Dungeon: Twilight vols. 1-2: Cemetery of the Dragon

Sfar, Joann (Author), Trondheim, Lewis (Author), Kerascoet, [none] (Illustrator)

NBM Publishing

Adventuregame Comics: Leviathan (Book 1): An Interactive Graphic Novel

Shiga, Jason (Author)

Abrams Fanfare

Pogo: The Complete Syndicated Comics Strips: Vols. 7 & 8 Gift Box Set (POGO COMP SYNDICATED STRIPS HC BOX SET)

Kelly, Walt (Author), Evanier, Mark (Editor), Kelly, Walt (Artist)

Fantagraphics Books

The Projector and Elephant

Vaughn-James, Martin (Author), Seth (Editor), Heer, Jeet (Introduction), Seth (Designer)

New York Review Comics

All Your Racial Problems Will Soon End: The Cartoons of Charles Johnson

Johnson, Charles (Author)

New York Review Comics

The George Herriman Library: Krazy & Ignatz 1922-1924

Herriman, George (Author), Herriman, George (Artist)

Fantagraphics Books

YOKAI

Yumoto, Koichi (Author)

PIE International

George Grosz in Berlin: The Relentless Eye

Rewald, Sabine (Author), Buruma, Ian (Contributor)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Käthe Kollwitz: A Survey of Her Work 1867 - 1945

Fischer, Hannelore (Editor)

Hirmer Publishers

Women Artists in Expressionism: From Empire to Emancipation

Behr, Shulamith (Author)

Princeton University Press

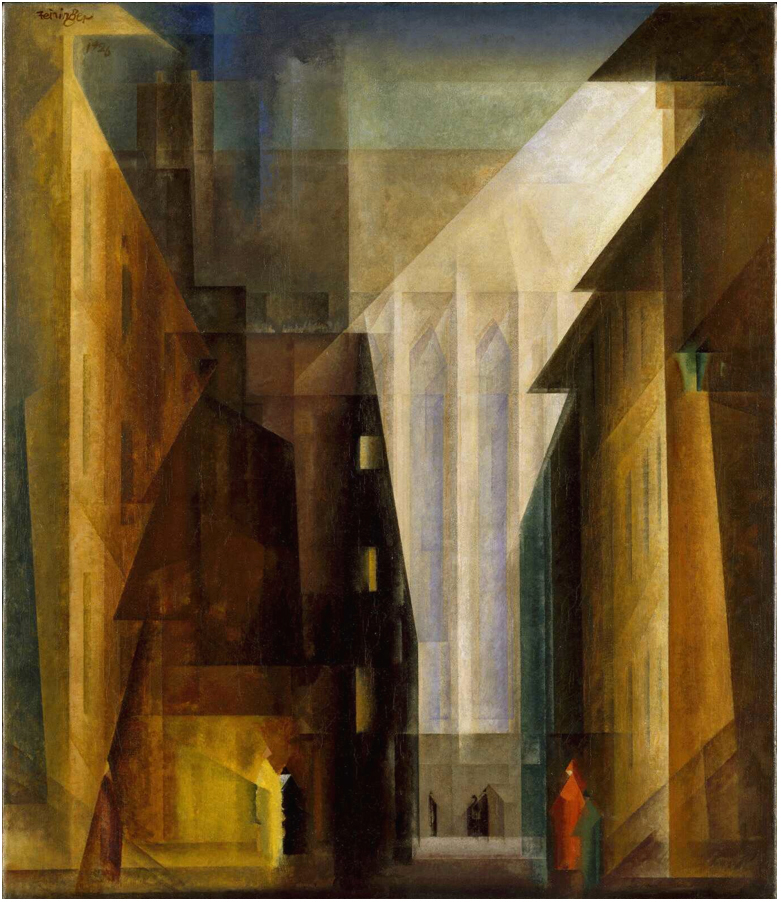

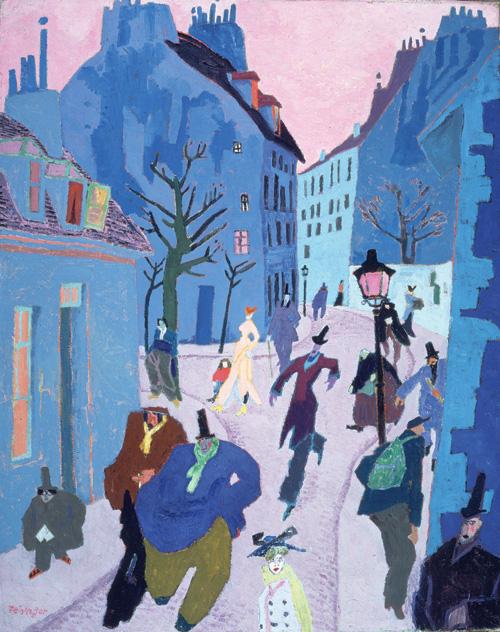

Austrian and German Masterworks: Twentieth Anniversary of Neue Galerie New York

Price, Renée (Editor), Lauder, Ronald S. (Preface)

Prestel

Guston in Time: Remembering Philip Guston (New York Review Books Classics)

Feld, Ross (Author)

NYRB Classics