Amount, Argument, Art, Be, Beautiful, Belief, Cause, Certain, Chance, Change, Clear, Common, Comparison, Condition, Connection, Copy, Decision, Degree, Desire, Development, Different, Do, Education, End, Event, Example, Existence, Experience, Fact, Fear, Feeling, Fiction, Force, Form, Free, General, Get, Give, Good, Government, Happy, Have, History, Idea, Important, Interest, Knowledge, Law, Let, Level, Living, Love, Make, Material, Measure, Mind, Motion, Name, Nation, Natural, Necessary, Normal, Number, Observation, Opposite, Order, Organization, Part, Place, Pleasure, Possible, Power, Probable, Property, Purpose, Quality, Question, Reason, Relation, Representative, Respect, Responsible, Right, Same, Say, Science, See, Seem, Sense, Sign, Simple, Society, Sort, Special, Substance, Thing, Thought, True, Use, Way, Wise, Word, Work.

I. A. Richards, How to Read a Page (1942)

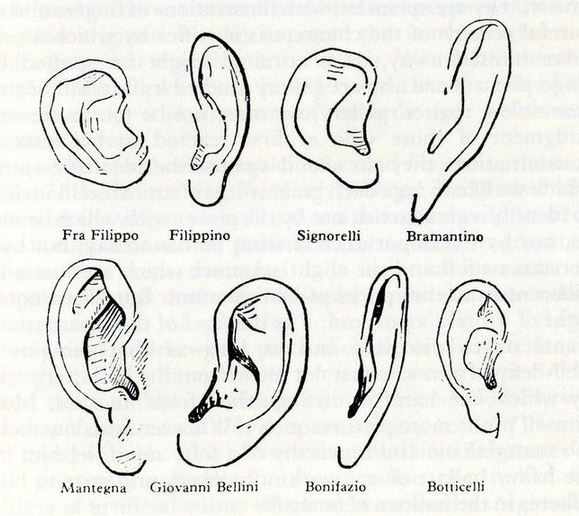

Richards began with the 850 words included in C. K. Ogden’s “Basic English” lexicon, intended to teach foreigners the maximum amount of English with the minimum amount of vocabulary. He selected those which he deemed most abstract and multifaceted, those which possessed “extreme versatility and ambiguity.” In fact, a word’s risk of being misunderstood is a significant criterion for inclusion.

This systematic ambiguity of all our most important words is a first cardinal point to note. But “ambiguity” is a sinister-looking word and it is better to say “resourcefulness.” They are the most important words for two reasons:

1. They cover the ideas we can least avoid using, those which are concerned in all that we do as thinking beings.

2. They are words we are forced to use in explaining other words because it is in terms of the ideas they cover that the meanings of other words must be given.

I have, in fact, left 103 words in this list—to incite the reader to the task of cutting out those he sees no point in and adding any he pleases, and to discourage the notion that there is anything sacrosanct about a hundred, or any other number.

I. A. Richards, How to Read a Page

Richards calls out a handful of words—Soul, God, Time, Space—as being equally ambiguous and important, but not functioning as tools of thought. (In the case of Time and Space, I’m not certain I agree.)

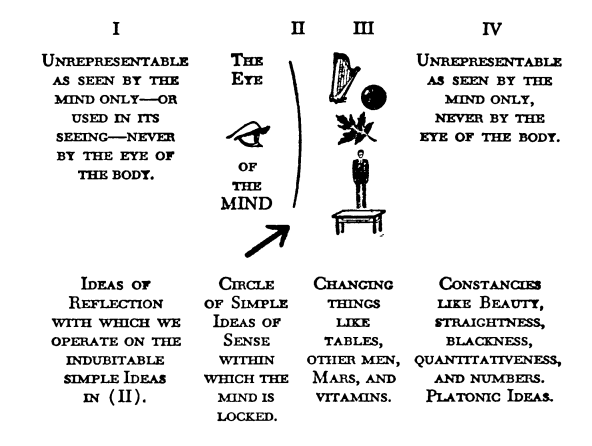

Learning to read—like learning to see how the catch on a door works—is becoming able to grasp some of the ways in which the parts of a complex system are dependent upon one another. The experience from which skill in reading derives is, of course, a vastly more complex and potent growth of universals than anything the cat can develop. Nonetheless, as with the cat, though much more so, the secret of success lies in the stabilization of universals in the soul. But the universals which good reading calls for concern the wide general ways in which minor universals of less scope may and may not fit together. What counts most is not familiarity with the senses of words taken separately but knowledge of their interdependencies.

…

If we can see how we read or misread “cause,” “form,” “be,” “know,” “see,” “say,” “make” . . . how we omit or fail to omit in taking their meaning, we develop our experience as readers better than in any other fashion. It is with these words that the major universals which should order our reading can best be held up for less ‘exclusive attention.’ These words, as we all know, vary their sense with their company. Their variations are patterns for all other words which follow the same forms. As these patterns grow in our minds they be come operative in thousands of places in connection with thousands of other words and without our ever being aware what unnamed forms have become our guides in interpretation.

I. A. Richards, How to Read a Page

This is not such a bad summary of why I have maintained that artificial intelligence has such a long way to go before it can comprehend and engage in human language. Human language has been constructed in the most ad hoc, holistic way imaginable.

Computers don’t manage so terribly with concrete and technical words, but what will AI do when it can understand those words and yet fall down on Richards’s list? What would language be like without those words?

Is that where human language is going under the influence of computers and AI?

A friend has suggested “Taste,” “Health,” and “Care” as worthy additions/substitutions to the list. I think “Value” and “Real” deserve a place. Do readers have other suggestions?