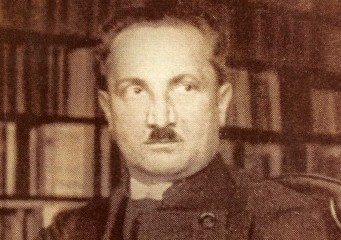

Heidegger’s Philosophy of Being, Herman Philipse (Princeton, 1998)

Herman Philipse makes very fine tombstones. Recently he published a book, God in the Age of Science?, criticizing much modern philosophical theology (e.g., purportedly rational arguments for being Christian) in far greater depth than atheist gadflies like Dawkins and Dennett have ever felt necessary. This particular tombstone is for Martin Heidegger: a very critical exegesis of his philosophy that ends with a damning verdict.

People have wondered for whom Heidegger’s Philosophy of Being was intended, since anyone willing to read this much about Heidegger is probably going to be favorably biased toward him. I suppose I am part of the target audience. I have an inclination toward what is evidently Philipse’s vice: getting inside of dubious systems and seeing how they collapse. I’m glad he has done the work on this one, though.

I take Heidegger seriously as a philosopher, unlike many of his scions. There’s no question that in terms of influence, he has wielded real substantive power over the 20th century, and there is certainly something compelling about his work. It is also very elusive and blatantly evasive. Philipse’s book is the first comprehensive synthesis of Heidegger’s work that I have read: all the other books I know of (almost all in English) either stick to Being and Time or else settle for summary overview or simple paraphrase. Philipse, having ingested as much of the literature as anyone, attempts to identify the driving motives behind all of Heidegger’s work and trace their course chronologically.

I think his attempt is for the most part convincing; where the details are debatable, the high level still seems broadly on the mark. Philipse takes Heidegger seriously. He scolds those who call Heidegger’s writing garbage, fascist, and/or pure nonsense. Heidegger’s work is obscure, probably needlessly so, but it’s not nonsense. Philipse criticizes Victor Farias and Tom Rockmore for calling Heidegger’s work intrinsically fascist, and he even chides Jürgen Habermas for condemning Heidegger too quickly. That Philipse nonetheless concludes with an extremely harsh assessment of Heidegger’s philosophy is a real problem for Heideggerians, one that cannot easily be dismissed. I have not seen a comprehensive competing account that contests Philipse’s book.

The estimable Taylor Carman, who has done some intriguing work on Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty, took great issue with Philipse, but I think that Philipse easily came out the victor in the argument. William Blattner, another sharp Heidegger scholar, was more willing to recognize the difficulties posed:

Heidegger’s Philosophy of Being presents significant challenges to the legitimacy of Heidegger’s ontological discussions. Unless we can justify Heidegger’s assumption that being must enjoy a form of unity that transcends its diversity into regions and epochs, and unless we can free his texts from their pseudo-religious, postmonotheist mythology, Heidegger’s celebrated Seinsfrage will collapse (as a piece of philosophy).

William Blattner, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Vol. 65, No. 2 (Sep., 2002), pp. 478-481

I think Philipse’s challenge still stands unanswered.

The Thesis

Central is Philipse’s thesis that Heidegger maintained a fundamentally religious tenor throughout all his work. Philipse is a staunch atheist and the association of Heidegger with religion is a dire sign, but it’s worth pausing to assess exactly what is meant by religious. Heidegger was raised Catholic and started in theology but rejected Catholicism utterly. The persistence of a religious framework in his writing is best expressed by his methodological appeal to a non-rational, ineffable fundamental and transcendent truth not subject to analysis or debate. (Note that I say “transcendent,” not “transcendental.”)

In this Heidegger follows Luther and Kierkegaard, as well as adopting Nietzsche’s methods and flipping them on their head to reject materialism instead of embracing it. Such claims are, of course, radically anti-pluralistic, anti-multicultural, anti-tolerant, and anti-liberal, and so Heidegger’s anti-humanistic positions follow from this method as much as they do from his philosophical ideas. Such values of rational assessment and debate would jeopardize the philosophy and so must be rejected.

It is this seizing of quasi-religious authority that bothers Philipse, and it bothers me as well. Philipse tries to evaluate the philosophy once removed from such self-puffery, and finds the remainder wanting. Heidegger indisputably cast a great spell over those he came into contact with, and over many who read his work. They included his teacher Husserl, Hannah Arendt, Karl Jaspers, Karl Löwith, and many others. He was able to convince a great many people that he was wrestling with something primordial and essential. Just in changing the terminology from that of Husserl’s phenomenology to his own phenomenological ontology, he staked out a seemingly higher ground. This orientation to an authority about the fundamental is what underlies Philipse’s claim that a religious authority underpinned all of Heidegger’s work from beginning to end.

Ironically, Philipse’s conclusion is not so far from that of Heidegger scholar Theodore Kisiel. Chakira recommended Kisiel’s The Genesis of Heidegger’s Being and Time as one of the best works on Heidegger, and indeed Kisiel is extremely comprehensive and thoughtful about the development of Heidegger’s early thought. Kisiel’s conclusion is that the essential bits of Heidegger’s philosophy were in place by 1919, expressed most coherently in Being and Time in 1927, and remained fundamentally unchanged thereafter until his death in 1976:

Could it be that the hermeneutic breakthrough of 1919 already contains in ovo everything essential that came to light in the later Heidegger’s thought? Could it be that there is nothing essentially new in the later Heidegger after the turn, for all is to be found at least incipiently in that initial breakthrough of the early Heidegger? Could it be that not only B T but all of Heidegger can be reduced to this First Genesis, the hermeneutic breakthrough to the topic in KNS 1919? Heidegger seems to suggest as much by using Holderlin’s line, “For as you began, so will you remain” (US 9317) to place his entire career of thought under a single “guiding star.”

Theodore Kisiel, The Genesis of Heidegger’s Being in Time (Conclusion)

This is, to some extent, a problem for some Heidegger scholars who would like to treat Being and Time as uniquely belonging to an early period of thought and the later, far less systematic work as fundamentally different and far less significant. In addition, after Being and Time Heidegger’s work is haunted by the specter of his mid-1930s Nazism and apparent lack of repentance thereafter, and so this problem is also avoided by way of a dividing line placed before the Nazi period. After Being and Time, Philipse sees a change in approach and presentation, but not in substance.

The Five Leitmotifs

Philipse posits five “leitmotifs” present in Heidegger’s work, one ever-present, two dominant in the early work and two in the latter. Blattner summarizes them more concisely than Philipse does, so I quote him here:

Philipse argues that in place of a coherent ontological theory, Heidegger weaves together five “leitmotifs.” There is

(1) a meta-Aristotelian theme: philosophy aims at discovering the unity of being beyond its diversification into subordinate categories.

In the early thought, the diversity of being is spelled out in

(2) a phenomenological-hermeneutic leitmotif: we access being through a series of regional ontologies that expose the holistic patterns of unity within various domains of entity, such as nature and Dasein. This “diversity pole” is complemented by

(3) a transcendental “unity pole:” the unity of being is uncovered through a regional ontology of the human, which simultaneously serves as an investigation of the possibility of the understanding of being in general.

After Being and Time the transcendental unity for which Heidegger strove gets historicized, yielding

(4) a neo-Hegelian deep history: Western culture is grounded in a series of global epochs of being, each of which makes possible a distinctive, transcendental sort of being. This “diversity pole” is then itself complemented by

(5) a postmonotheist mythology: each epoch of being is a dispensation of Being as a transcendent, concealed non-phenomenon, from which Western culture has been falling away since the time of the presocratics and for a second coming of which we must prepare ourselves by way of a radical, non-rational form of “thinking.”

William Blattner, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Vol. 65, No. 2 (Sep., 2002), pp. 478-481

In addition, the change of method after Being and Time, as well as the switch from “being” (the gerund) to “Being” (the proper noun), stem from Heidegger’s failure to make the second and third leitmotifs work together in a systematic fashion. So all traces of phenomenology and phenomenological method get dropped, along with much of the philosophical framework that led up to them, in favor of a vigorously irrational and mystical theology that attempts to combine Kierkegaard and Nietzsche.

I will not try to tackle the sufficiency or the accuracy of these leitmotifs here. Philipse works hard to close-read huge chunks of Heidegger’s corpus within this framework. Lacking such familiarity, I can only say that Philipse seems to conduct his analysis fairly and thoroughly. I was in the best place to judge with regard to Being and Time and some of the later work, and while many of his points seem debatable, Philipse never appeared to lose the plot in the way that Carman accuses him of doing.

Philipse emphasizes the purely negative approach of so much of Heidegger’s work, which consists of discarding or otherwise demoting methods of inquiry that could compete with his own ontological investigations. These are not incidental to Heidegger’s philosophy. They are a necessary component to it because, as Philipse repeatedly shows, treating Heidegger’s philosophy critically, from the outside, by nearly any alternative approach, exposes gaping chasms. Only from within does the edifice hold up, and even then….

Being and Time

Philipse’s treatment of Being and Time focuses on its methodology, which time and again shows up as deficient. The main problems are that Heidegger frequently begs the question, or else muddies the waters by drawing a distinction between what he is doing and what everyone else has done, which then does not stand up to scrutiny.

Philipse demystifies it piece by piece. I’ll focus on only one particular and significant problem here, which is Heidegger’s crucial yet unjustified claim to have access to the question and structure of being, independent of all particulars and all theory: one white European man has grasped the fundamental ontology of being without needing to so much as glance at another culture.

Dasein has understanding not only of its ontical possibilities, but also of its essential constitution of being (Seinsverstandnis). If this is the case, Heidegger assumes, Dasein will be able to articulate conceptually its understanding of its essential constitution of being, that is, to develop an ontology of itself, independently of empirical research on the varieties of human life and culture. Because we allegedly possess this possibility, Heidegger says that Dasein is ontological. Unfortunately, in giving this answer Heidegger assumes what is to be explained, to wit, how it is possible to understand the essence of being human without doing ample empirical research in anthropology.

This is a very old sin, yet far less justifiable in 1927 post-Sapir/Whorf, when the cracks in the universalist tendencies of Western Culture had long been on display for all to see. But leaving the problems of universalism itself aside, Heidegger is nonetheless depending on some kind of transcendental framework to justify his claim of access to ontological structures.

Assuming that the ontological interpretation of Dasein is based on a presupposed ontic ideal, will its results not be arbitrary, because the presupposed ideal is a matter of free choice? Will we not interpret the ontological structure of Dasein differently if we choose another ontic ideal of authentic existence? If this is the case, as it seems to be in view of the many different interpretations of human existence by Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, Levinas, and others, should we not abandon the claim that the ontological analysis of Dasein yields knowledge? In section 63, Heidegger denies that this skeptical conclusion is justified. But his argument confronts him with a dilemma. He stresses that there are formal aspects of the ontological structure of Dasein as interpreted by him, such as the self-interpretative nature of Dasein in general, which do not depend on a particular ontical project. The problem is that this thesis conflicts with Heidegger’s theory of interpretation, according to which all features of Dasein’s ontological structure can be discerned only in the light of a specific existentiell project and its forestructure. As a consequence, Heidegger should either admit that he contradicts his theory of interpretation, or he should restrict the scope of this theory to applicative interpretations and leave room for other types of interpretation, such as objective or theoretical interpretations. In the latter case, he could draw a distinction within the analysis of Dasein in Sein und Zeit between purely ontological analyses, which are independent of any specific ontic ideal, except of course the ideal of seeing the ontological constitution of human life as it is, and ontically contaminated analyses, which presuppose a specific ontical ideal. I argue below that amending Sein und Zeit in the latter sense is mandatory.

In brief, Philipse here criticizes Heidegger for formulating a single ultimate notion of “authenticity.” Not only does Heidegger not justify his notion of authenticity, but the very framework he has embraced–the “phenomenological-hermeneutic” and “transcendental” leitmotifs, specifically–makes it impossible to privilege any particular notion of authenticity as being ultimate.

Philipse lays some of the blame at Husserl’s feet, saying that Heidegger simply brought to an extreme longstanding problems with the very notion of access to phenomenological structures of experience.

Husserl’s mature conception of phenomenology is characterized by four elements: (1) phenomenology is a purely descriptive discipline, which avoids all theorizing; (2) phenomenological description of the way in which entities are “given to” or “constituted in” transcendental consciousness is equivalent to an ontological elucidation of their mode of being (Seinsweise, Seinssinn), because (3) the “being” of entities is identical with their being constituted in transcendental consciousness. Finally, (4) transcendental phenomenology is possible as an “eidetic” discipline, which consists of synthetic a priori propositions about essential structures. Clearly, each of these four tenets is problematic. The principle of description (1) presupposes that theory-free description is possible. The idea of a phenomenological ontology (2) assumes that the manner of being of entities or their ontological constitution is identical to the manner in which they appear to us, and this, in its turn, presupposes Husserl’s transcendental idealism (3), that is, the view that the world, and all entities other than transcendental consciousness, are ontologically dependent on transcendental consciousness because they are constituted by it. Element (4), finally, will be rejected by the great majority of modern philosophers, for they repudiate the notion of a synthetic a priori discipline. In section 7 of Sein und Zeit, where he elucidates his notion of phenomenology, Heidegger at first endorses (1), (2), and (4), whereas he rejects Husserl’s transcendental idealism (3).

Now, the rejection of transcendental idealism is a major problem for Heidegger. Taylor Carman’s critique of Philipse insists that Heidegger’s modifications to Husserlian phenomenology in fact allow Heidegger to escape these charges. I am with Philipse, however, in thinking that Heidegger’s modifications simply result in rendering phenomenology incoherent. Husserl, who never begged off a difficult problem, knew that transcendental idealism was required if there was going to be any possible way of justifying the eidetic phenomenological method–mind, object structure, and world could not line up properly otherwise. (I’ve never seen an account that manages it, anyway.) By cavalierly ignoring the problem and appealing to some sort of basic realism, Heidegger has devoured a supersized transcendental free lunch. His postulation of moods as more fundamental than intentions is interesting, but in no way logically coherent in the way that he claims. Jumping to the assumption of privileged access, of course, makes Heidegger’s work more immediately appealing and less leaden than Husserl’s, at the cost of its internal coherence.

Philipse puts it as follows:

We must conclude that in this intuitive sense of the term “category” Heidegger was wrong in claiming that the same categories cannot apply both to inanimate things or tools and to Dasein, whereas we did not succeed in finding another sense of “category” that would make Heidegger’s claim plausible. As a consequence, there simply is no interesting philosophical program of constructing specific categories for human life. A philosopher might explore a great number of concepts in which human beings express their understanding of life. But it is not fruitful to claim that some of these concepts are categories or “existentialia,” whereas others are not. In other words, there is no distinction left between the ontological and the ontical if Heidegger’s theory of essential structures is discarded.

Another way of phrasing this point would be: categories require theory and theory requires categories. There are no pre-theoretical categories.

Given that the methodology of Being and Time is fatally compromised and its authority cosmically self-inflated, what remains? A fair bit of stuff about everyday practices, how we engage with the world, how we conceive of ourselves vis-a-vis death, and other talk about the human condition. Much of this forms the basis of the quasi-pragmatic interpretation of Heidegger formulated most famously by Hubert Dreyfus in Being-in-the-World, a book which Philipse cites approvingly as a rigorous and critical engagement with Being and Time. This effectively gives up the transcendental pole and renders much of Being and Time irrelevant, preserving only certain epistemological aspects. One could argue that Sartre rescues other aspects of Heidegger’s philosophy in Being and Nothingness through a somewhat similar mechanism, as Sartre simply argues that authenticity is simply something that we can’t reach.

So some of Heidegger’s concepts, extracted and reprocessed, partly survive their faulty surroundings. The methodology and the system do not, however. The methodology, it seems, also failed for Heidegger, since he never even attempted such a systematic philosophical project again.

The Turn and the Later Work

Heidegger abandons systematic philosophy completely after Being and Time and turns to a historical and essayistic approach with more overt mythologizing. (“Only a god can save us now,” etc.) Philipse’s most intriguing analogy here is that Heidegger was posturing himself as a post-Nietzschean Martin Luther, trying to wipe away the human and social crud separating us from God (or whatever is left of him). Since Heidegger wished to save religion in the absence of a god, his attempt was fundamentally doomed, and so his later work is at odds with itself substantively in a way that the earlier work is not.

The core of the postmonotheist leitmotif is the idea that traditional monotheism died because Being was misinterpreted as a being, God. The postmonotheist strategy purports to destroy monotheism and to rescue religion by arguing that monotheist faith, which died, is not the true religion. True and authentic faith is the thinking of Being. This strategy faces a dilemma. On the one hand, postmonotheology should resemble traditional monotheism sufficiently for satisfying similar religious cravings. Indeed, we saw that the meaning of Heidegger’s postmonotheist thought is parasitic on the Christian tradition. On the other hand, postmonotheism should not resemble traditional monotheism too closely. For in that case, it could be interpreted as just another variety of the deceased monotheist tradition, as a watered-down and more abstract version of Christianity, a substitute religion, and the postmonotheist strategy will fail altogether.

Philipse maintains, however, that the religion was present in Heidegger’s work all along, and perhaps the central piece of evidence here is Heidegger’s assessment of his philosophical development from 1938:

But who would want to deny that on this entire road up to the present day the discussion [Auseinandersetzung] with Christianity went along secretly and discreetly [verschwiegen]—a discussion which was and is not a “problem” that I picked up, but both the way to safeguard my ownmost origin—parental home, native region [Heimat], and youth— and painful separation from it, both in one. Only someone who has similar roots in a real and lived catholic world may guess something of the necessities that were operative like subterranean seismic shocks [unterirdische Erdstöβe] on the way of my questioning up to the present day …

It is not proper to talk about these most inner confrontations [innersten Auseinandersetzungen], which are not concerned with questions of Church doctrine and articles of faith, but only with the Unique Question, whether God is fleeing from us or not and whether we still experience this truly, that is, as creators [als Schaffende]…

What is at stake is not a mere “religious” background of philosophy either, but the Unique Question regarding the truth of Being, which alone decides about the “time” and the “place” which is kept open for us historically within the history of the Occident and its gods …

But because the most inner experiences and decisions remain the essential thing, for that very reason they have to be kept out of the public sphere [öffentlichkeit].

Heidegger, My Way Up to This Moment (1937-1938)

Religion, at least in the broadest sense of the term, has been on Heidegger’s mind the whole time.

And so Philipse tells a story stressing the continuity of Heidegger’s thought despite the change in approach. What remains after the systems and methods of Being and Time are discarded are the same fundamental elements: privileged access to the essence of being/Being, and the dismissal of all other methodologies and disciplines (politics, science, technology, materialism) as superficial, incomplete, or irrelevant. His work, if anything, becomes more solipsistic, as engagement with any other thought would be enough to threaten the unjustified seizure of authority upon which it relies.

His aggressive misreading of Nietzsche is his last sustained engagement with philosophy, which then gives way to short quotes from writers and philosophers and generalizations about culture and history. (And puns.) There is always the insistence that humanity is ignoring some “more original” and “more primordial” truth that Heidegger, naturally, is trying to illuminate. (I take those phrases from what must be Heidegger’s most overrated work, “The Question Concerning Technology.”)

Taking the lead from Nietzsche, his method of of interpretation becomes explicitly violent and presumptuous:

The authentic interpretation [eigentliche Auslegung] should show that which is not stated in words anymore but which yet is said. In doing so, the interpretation must necessarily use violence. The proper sense [das Eigentliche] should be looked for where a scholarly [wissenschaftliche] interpretation does not find anything anymore, although the latter stigmatizes as unscholarly [unwissenschaftlich] everything that transcends its domain.

Heidegger, Introduction to Metaphysics (1935)

Yet whatever subversive cool hovers around such violent and authentic interpretation should not disguise what this method is and has remained from Heidegger through Derrida, de Man, and Fish: the assumption of privilege. Here it is undisguised, in Philipse’s words:

Sometimes Heidegger claims that he has a specific epistemic gift for discerning what Being sends us, and he compares those who do not have this gift to people who are color-blind. Unfortunately, this analogy with color-blindness does not withstand critical scrutiny. Color-blindness can be explained by specific defects in our visual apparatus, whereas I suppose that the inability to grasp what Heidegger claims to be discerning cannot be so explained. Heidegger relies on a epistemic model derived from theology, and assumes that he is the recipient of some kind of revelation.

What Heidegger counts on, then, is that we will simply believe what he says. He uses a number of authoritarian rhetorical stratagems in order to obtain this perlocutionary effect, and he is remarkably successful in securing it.

Philipse points out that the unwarranted, rhetorical assumption of privilege weaves its way through all of Heidegger, as when Heidegger disregards plain old empirical “vulgar” history in favor of his own practice of “real history.” Once again, the empirical and methodological legwork usually required in such disciplines is trumped by Heidegger’s claim to have made an end-run around them to the very depths of being.

“History” in the habitual sense of the word designates both the sum of human actions, artifacts, and forms of life in the past, and the discipline that studies these actions and forms of life. Because Heidegger in section 7 of Sein und Zeit calls empirical phenomena “vulgar” phenomena, we might label empirical history “vulgar” history. To vulgar history, Heidegger opposes real or authentic history (eigentliche Geschichte), which is the sequence of fundamental stances underlying vulgar history. Real history is “necessarily hidden to the normal eye.” It is the history of the “revealedness of being” (Offenbarkeit des Seins). Heidegger’s later “historical mode of questioning” (geschichtliches Fragen) aims at making explicit fundamental stances of Dasein amidst the totality of beings. Since these stances allegedly can be studied independently of empirical history as an intellectual discipline, Heidegger’s doctrine of real history implies that the philosopher is the real historian, and that by reconstructing the sequence of metaphysical structures, he does a more fundamental job than the historian in the usual sense is able to do. Heidegger often intimates that his historical questioning is also more fundamental than historical research done by historians of philosophy, and that it may brush aside the methodological canon of historical philology and interpretation. As Joseph Margolis observes, Heidegger’s doctrine of real history “manages to ignore the concrete history of actual existence and actual inquiry.”

Which is not to say that Heidegger is not capable of insight, only that the insights are repeatedly and terminally dressed up in almost unforgivable pomposity and presumption.

The Assessment

The latter, critical parts of Heidegger’s Philosophy of Being are less effective than the analysis because Philipse has already done the heavy lifting just in uncovering the structure of Heidegger’s thought. The five leitmotifs, if truly present and central, are already so damning that when Philipse later slices and dices Heidegger’s language to show that it’s slippery and bad philosophy, his arguments follow very easily from his earlier analytic interpretation.

Philipse has a great fondness for the ordinary language philosophy of Wittgenstein, Austin, and Ryle, but his methodological application of it to Heidegger’s thought yields its most fruitful results in his structural analysis, before Philipse critiques Heidegger and explicitly contrasts these thinkers favorably with Heidegger. Philipse’s comprehensive structural organization and presentation of Heidegger’s thought is the major achievement here, in itself enough to relay much of the criticism he subsequently makes.

Despite Philipse finding methodological failings in Habermas’ assessment of Heidegger, their accounts dovetail in certain important respects, particularly how Heidegger’s methodological failures make his results arbitrary:

The language of Being and Time had suggested the decisionism of empty resoluteness; the later philosophy suggests the submissiveness of an equally empty readiness for subjugation. To be sure, the empty formula of “thoughtful remembrance” can also be filled in with a different attitudinal syndrome, for example with the anarchist demand for a subversive stance of refusal, which corresponds more to present moods than does blind submission to something superior. But the arbitrariness with which the same thought-figure can be given contemporary actualization remains irritating.

Jürgen Habermas, The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity

Being and Time inspired far less self-contradictory work by Sartre and Merleau-Ponty, but the roots of their work are arguably more in Husserl more than Heidegger. Heidegger’s work, however, may have provided a rhetorical force for some of Husserl’s observations that the brilliant but chronically leaden Husserl never managed. Heidegger, patricidal to the end, played down his debts to Husserl as much as possible, but it is unclear both to me and to Philipse what Being and Time added to phenomenology, substantively. Ernst Tugendhat put the point this way:

What Heidegger obtained through his argumentation is only the position of Husserl. The decisive step beyond Husserl is no longer substantiated through argumentation; indeed, it is not even recognizable as an independent step.

Ernst Tugendhat, “Heidegger’s Idea of Truth” (1984)

What remains then? Metaphors, or, as Carnap would say, poetry. And while Carnap called it bad poetry, I’d say some of it is fairly good poetry. “The Origin of the Work of Art” remains a forceful and evocative essay, and especially in light of the collapse of Being and Time‘s foundations, I’m nearly ready to rank it over Being and Time.

Of the Nazism, I broadly agree with Philipse. Heidegger’s philosophy does not necessarily imply Nazism, but following it does make it more likely that one will embrace of something like Nazism: a blunt, irrational, cult of tribalism uniting people around a charismatic leader. There is no question that Heidegger’s embrace of Nazism gained strength from his philosophical convictions, but those convictions did not mandate Nazism per se. Heidegger was unlucky in having the particular cult to which he was attracted turn out to be one of the most virulent of all time. This excuses him in no way, but it does remove the stigma from the work itself. Such is not the case for Carl Schmitt or Ludwig Klages, whose philosophy contains far more inherently fascist elements rather than merely cultic or irrationalist ones. Nonetheless, you’d have to be nuts to use Heidegger’s work as political philosophy; likewise, I’m mildly horrified whenever someone like Avital Ronell praises Heidegger’s personal choices in his life.

Likewise, I think that Heidegger’s philosophy is not coincidentally the product of his being a generally horrible person. Leaving aside the Nazi issue, his treatment of basically everyone he ever came into contact with, from Husserl to Hannah Arendt to his colleagues and students, tended toward the selfish, callous, and profoundly exploitative. Few philosophers seemed to treat people as means to an end as exclusively as Heidegger did. Both of the Heidegger biographies by Hugo Ott and Rüdiger Safranski paint the man as frighteningly charismatic but devoid of warmth and loyalty. I may write a follow-up post about Heidegger’s life to talk further about his personality traits, but for now I will just say that I draw a connection between such callousness and Heidegger’s conviction that he was dealing with a realm of truth greater than that which any other human being had touched in millennia.

I think that Philipse does, however, give an impression of there being too much calculated intention behind Heidegger’s philosophy. I believe that the unity he observes is present, but I think Philipse somewhat overstates the degree to which Heidegger’s philosophy was a conscious attempt to instill a new religion of Being. I think Heidegger was too disorganized and confused to pull something like that off. Philipse, quite organized and systematic himself, may have read too much of those traits into Heidegger. This is a small point, but I think it does result in Philipse giving Heidegger a bit too much credit.

Yet Philipse has a second interpretation to unify Heidegger’s work which bears mentioning, tracing the problem of authenticity as Heidegger himself might have faced it:

Now I want to suggest that the burden of authentic resoluteness as Heidegger sees it is in principle unbearable. It is simply impossible to be resolute without relying somehow and to some extent on preexisting cultural roles and norms. This is why Heidegger’s individualistic notion of authenticity, according to which Dasein has to liberate itself from common moral rules in order to choose one’s hero freely, tends to collapse into a collectivist notion, according to which the choice is not made by an individual at all, but is predetermined by the destiny of the Volk to which one belongs. Once Dasein has become authentic by liberating itself from standard morality, life becomes unbearable, and the liberated individual will seek to shake off the burden of radical individuation (vereinzelung) by joining a collectivist mob.

If this interpretation is acceptable, there is no direct relationship between the ideal of authenticity in Sein und Zeit and Heidegger’s turn to Nazism. The unbearable burden of authentic life can be relieved in two ways: by a leap to faith and by a totalitarian commitment. Only when the first solution seemed to be ruled out did Heidegger jump to the second. Nietzsche’s thesis of God’s death explained why the first solution was not available, and the metaphysics of the will to power paved the way to a second solution: Nazism.

I want to look at this psychologically and biographically. As depicted in biographies, the unempathetic and selfish Heidegger never seems to possess any sense of belonging to a group of peers. Lacking human compassion and solidarity, his search for authenticity had no choice but to take theological and tribal forms. His relations to others were those of power: he was a student (of Christ, of Husserl, of Hitler), or more often he was a teacher, or rather a leader, since “teaching” is not quite the word for what Heidegger intended to do. His dictum to his students was always, “I don’t want you to think. I want you to see.”

Milton set about to “justify the ways of God to man.” Once God is in the business of needing justification, He is doomed. Heidegger’s project was to disassemble that need, for God and for himself.

Appendix: Heidegger’s Sophistry of Being

If nothing else, Heidegger was a brilliant rhetorician, and though not as important to the book’s thesis as the points above, Philipse’s list of his authoritarian rhetorical stratagems is quite handy, if only to see how they too have woven their way through so much philosophy before and since. I have abbreviated this section heavily and excluded two more specialized stratagems. Philipse counts them as characteristic of the later work in particular.

1. The Stratagem of the Fall. If the Neo-Hegelian and postmonotheist doctrines were true, modern man would be fated to err. Heidegger erred grandly, because he erred in accordance with the present fundamental stance of the will to power. His opponents, however, err in petty ways, because, disagreeing with Heidegger, they do not acknowledge what is in our times, even though they are unwittingly determined by the present fundamental stance. Heidegger holds that logic is bound up with a false metaphysics that conceals Being, and that language in its ordinary uses blinds us to the light of Being as well. For this reason, opponents of Heidegger’s philosophy who try to state their objections clearly and pay heed to the principles of logic, need not be refuted: the very medium of their thought is condemned beforehand, because they have fallen from the House of Being. Christians sometimes held that everything, from language to inanimate matter, had been corrupted by the Fall. Similarly, Heideggerians suggest that all ways of philosophizing other than their own are contaminated, and that one does not need to show this in detail. These ways of philosophizing simply belong to the “reign of technology” (das Wesen der Technik), or to the “era of information,” to “logocentrism,” or to whatever other pejoratively labeled comprehensive category Heideggerians may invent. All philosophers are in Plato’s cave, except the Heideggerians.

2. The Stratagem of the Radical Alternative. If everything that human beings do or think is contaminated by the Fall, redemption must consist in an alternative that is radically different from anything we are able to conceive of: an entirely new Beginning. The conjunction of stratagems (1) and (2) puts the Heideggerian in a comfortable, because unassailable, “position”: he may condemn all other philosophical doctrines and movements in the name of an alternative that is ineffable because it is radically different: the Saving Event.

3. The Stratagem of Undifferentiating Abstraction. Heidegger tries to characterize the fundamental stance of the present epoch by stretching indefinitely the extension of nouns such as “technology” and “information.” We have seen that these nouns become meaningless by such an abstraction, even though Heidegger pretends that he is still using them meaningfully. I call this type of abstraction undifferentiating because Heidegger suggests that differences between items within the extension of these empty terms do not really matter and are indifferent. In 1935 he said that Russia and the United States are “metaphysically the same”; in 1945 he contended that communism, fascism, and democracy belong to one and the same metaphysical reality of the will to power; and in 1949 he ventured the opinion (which I quoted already) that “agriculture is now a mechanized food industry, in essence the same as the manufacturing of corpses in gas chambers and extermination camps.”

4. The Stratagem of Persuasive Redefinition. Theologians are masters of persuasive redefinition. It used to be the case that believing Christians were not allowed to doubt religious dogmas, but as soon as doubting the literal truth of the New Testament became widespread, theologians such as Paul Tillich were quick to point out that “real” faith does not exclude doubt. One has “faith” as long as one has an “ultimate concern” in life. Nearly all core concepts of Christianity have been redefined in the course of Western history, because religious dogmas had become unacceptable in their original sense. Heidegger often uses this strategy of persuasive redefinition, and he applies it not only in the later works.

5. Strategies of Immunization. Heidegger’s notion of thinking as questioning is one strategy of immunization among others. Heideggerians often claim that criticism of what Heidegger says must be due to misunderstandings. This is a time-honored theological strategy: if the Bible is God’s word and if God is infallible, we will never criticize the Bible as long as we understand it well. Similarly, if what Heidegger says is in fact what Being gives us to understand, and if Being is the only source of Truth, as Heidegger suggests, then we should not criticize Heidegger’s later writings. I do not want to deny that criticisms may be unfair; surely they might be due to misunderstandings. But this cannot be the a priori predicament of all possible criticisms, unless Heidegger’s postmonotheist doctrine of being is true and unless Heidegger is infallible. It is at this very doctrine that my criticisms are aimed.

8. Stratagem of the Elect. One will wonder how Heidegger could claim that he was able to raise and understand the question of Being, if Being is concealed and the Fall has been completed. How could he gain access to the impenetrable and hidden place from where he was able to experience the Truth of Being, if this truth remains concealed to ordinary mortals? Heidegger lectured repeatedly on Plato’s simile of the cave, and Plato’s simile provided him with the solution to this problem. Heidegger belonged to the elect, to those favored by Being, who were destined to hear Being’s voice. In Beitrage zur Philosophie, the theme of the elect occurs again and again. Perhaps it had to overcompensate for Heidegger’s isolation and lack of success in the Nazi movement.

Philipse links these stratagems to religion. While the links are obvious, I would not say they originate with religion nor are they necessarily indicative of religious thinking per se–certainly secular politics and science have made use of them as well. They are so ubiquitous that Heidegger stands out mostly for the force and skill with which he deployed them, which would do Grover Norquist proud. Likewise, I think that many of the people who have been attracted to Heidegger’s philosophy and methodology have done so not because of its religious revivalist content (though some, such as Levinas, clearly were attracted to it for precisely this reason) but because of the authoritarian rhetoric it offers.