It closes in just a couple days, but I loved the Xenakis Exhibit at the Drawing Center. Being able to look at the scores and plans while listening to the relevant pieces (on complimentary iPod!) was revelatory for me, particularly the extended coverage of Xenakis’s seminal Metastasis. (A nice little primer on the early stuff. I was also unaware of his absolute opposition to chance operations, improvisation, or performer choice.)

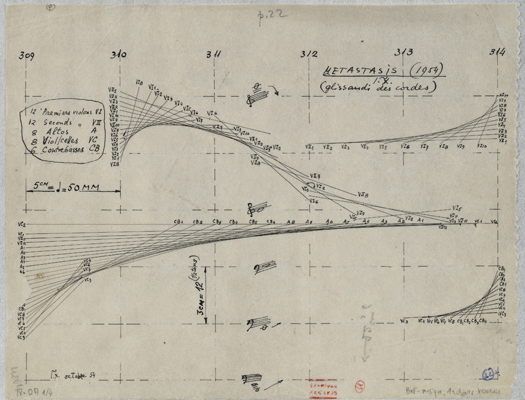

Study for Metastasis

This and others showed the hyperboloid curves that Xenakis used to generate the series of glissandi for a string ensemble, each instrument scored individually. Here’s the result:

Metastasis

At least for me, it vindicated how effectively Xenakis’s work does portray the graphic forms sonically, rather than sinking into impenetrable abstraction as Stockhausen’s far denser work frequently does. Xenakis really did have a rather atatvistic, populist conception of music (aided in popularity, no doubt, by the psychedelic era, which led to people like AMM getting major label recording contracts) that shows up in his own writing, where on several occasions he insists that his techniques are in the service of generating music that is intuitively graspable. The program included this quote from his early essay “The Crisis of Serial Music,” where he doesn’t sound so far from many of the more conservative critics of serialism (even daring to mention “the audience”!).

Linear polyphony destroys itself by its very complexity; what one hears is in reality nothing but a mass of notes in various registers. The enormous complexity prevents the audience from following the intertwining of the lines and has as its macroscopic effect an irrational and fortuitous dispersion of sounds over the whole extent of the sonic spectrum. There is consequently a contradiction between the polyphonic linear system and the heard result, which is the surface or mass. This contradiction inherent in polyphony will disappear when the independence of sounds is total. In fact, when linear combinations and their polyphonic superpositions no longer operate, what will count will be the statistical mean of isolated states and of transformations of sonic components at a given moment. The macroscopic effect can then be controlled by the mean of the movements of elements which we select. The result is the introduction of the notion of probability, which implies, in this particular case, combinatory calculus. Here, in a few words, in the possible escape route from the “linear category” in musical thought….

To paraphrase: forget individual manipulation of notes and tone rows, and focus on macroscopic presentation of dynamics, effects, densities, timbres, etc.

It would be empty speech if Xenakis’s work, or at least the best of it, didn’t succeed so viscerally in realizing his aesthetics (and listening to some of his followers reveals how easily things can go wrong–sorry spectralists!). I think his grasp of timbre and texture far outweighed many of his contemporaries (though granted, many weren’t interested in such things anyway), putting him closest to Messiaen and Varese, who both supported him.