Durkheim (not that one) wrote about my account of Blumenberg:

I think that Blumenberg is much more positive about the modern age than you suggest. Indeed, one might even compare his remarks on science – particularly its institutionalisation of method – with those of Popper. Popper of course would have no time for myth, but Blumenberg’s genius was to have shown that myth too can be defended in a similar way to science. The never ending variation that is the history of myth’s rewriting is comparable to the infinite progress that is the fate – and the triumph – of modern science.

I agree with this and I didn’t mean to give the impression that Blumenberg is a pessimist. In fact, Blumenberg’s ire seems reserved for those conservative pessimists like Schmitt, Loewith, or even Voltaire, who define the present moment as a crisis and look back to the past to try to find some point where we went wrong. He has even less patience for those, from Epicurus to the Gnostics to Kierkegaard, who ask that we should turn our back on the world and seek some private, otherworldly transcendence. And I do believe that Blumenberg’s endorsement of curiosity, science, and a secular interest in improving the world amounts to a prescription for a pragmatic progress: the right for humanity to explore, experiment, err, and positively evolve.

It is so optimistic, in fact, that it is difficult for me to accept enthusiastically. If I believe that a humanistic science offers the best way forward for the people on this planet, it’s only because I can’t think of any better ideas, not because I am filled with hope that things will work out. Blumenberg is more of a believer, and the faith he holds seems best portrayed in Blumenberg’s touching portrait of Husserl:

Scarcely a decade after theory, as mere gaping at what is ‘present at hand,’ had been, if not yet despised, still portrayed as a stale recapitulation of the content of living involvements, it was the greatness of the solitary, aged Edmund Husserl, academically exiled and silenced, that he held fast to the resolution to engage in theory as the initial act of European humanity and as a corrective for its most terrible deviation, and that he required of it a rigorous consistency, which is still, or once again, felt to be objectionable. Hermann Lübbe has described as the characteristic mark of this philosophizing, especially in the late works, the “rationalism of theory’s interest in what is without interest”: The existential problem of a scholar who in his old age was forbidden to set foot in the place where he carried on his research and teaching never shows through, and even the back of the official notice that informed him of this prohibition was covered by Husserl with philosophical notes. That is a case of ‘carrying on’ whose dignity equals that of the sentence, ‘Noli turbare circulos meos’ [Don’t disturb my circles].”

The Legitimacy of the Modern Age, III.Introduction

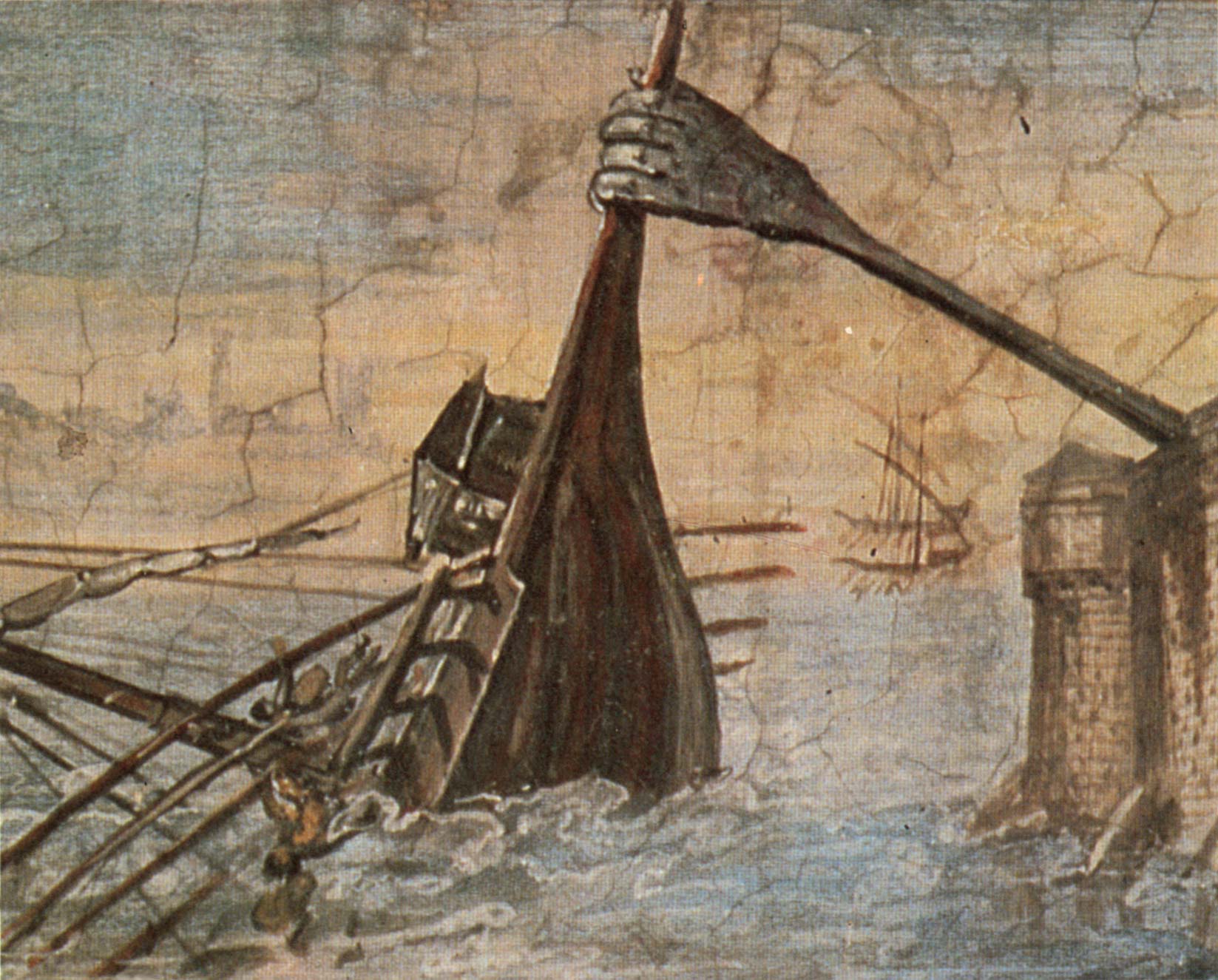

Let’s leave aside that Archimedes, in addition to being killed while working on theoretical math, had also designed warships and this claw:

The ideal here is that of a scholar who can retain his absorption in theory even as the surrounding chaos nearly envelops him. Here, for Blumenberg, it is theory that acts as the linking and growing mechanism of humanity. (And as commenter Durkheim suggests, theory is something of a halfway point between myth and science.) The danger is, of course, that theory turn into something as private as Gnosticism. What is it that gives Blumenberg and Husserl the assurance that they have not disappeared into a private fount of knowledge irrelevant to the greater world? This is a crucial question for Blumenberg to answer in the context of the book. I think that the answer, which is hinted at above, is that there needs to remain some sort of firm method, that “rigorous consistency” that Blumenberg mentions: the placing of the external world as authority and arbiter rather than one’s own self-certainty. (Here, Blumenberg separates from Hegel and moves back to Kant.) Again, I see this as a pragmatic methodology more than anything else, except that there was no such named tradition in Germany.

The other somewhat orthogonal point is how Blumenberg contrasts Husserl with Heidegger, who goes unnamed but is sniped at as the person who attacks Husserl’s theory as “gaping at what is ‘present at hand'”. Blumenberg implicitly connects Heidegger’s political beliefs with Heidegger’s priority of the “at hand” and activity over cognition and observation. Heidegger’s political associates bar Husserl from the library at which he studied. Heidegger removes the dedication to Husserl from Being and Time. Husserl stands back. He keeps working. And Husserl remains one of the least alluring, least sexy philosophers ever. He never cheats, he is never cheap, he is never glamorous. (Even his glamorous successors–Derrida and Sartre–did not put a shine on him.) He just keeps working things out.

I don’t want to enter that eternal debate on Heidegger, but I do sympathize with the emphasis Blumenberg places on detached observation, on the classical act of thinking and theorizing that still seems to have gone missing amidst unending talk of politics, subversion, performativity, and so on. (To those who say that detached observation is a luxury, the subsequent activities are no less luxuries.)

When I quoted Satie the other day (apparently an appropriate quote, thank you Dennis), it was this contrast between theory and action that I was thinking of: youth in action, old age in reflection. As every development in culture and technology (hello, the web) rushes to celebrate and analyze itself before it has barely begun to be anything at all, the nonstop circle of activity exhausts me, and I want to be the rigorous, consistent theorist myself:

Deeply lost in the night. Just as one sometimes lowers one’s head to reflect, thus to be utterly lost in the night. All around people are asleep. It’s just play acting, and innocent self-deception, that they sleep in houses, in safe beds, under a safe roof, stretched out or curled up on mattresses, in sheets, under blankets; in reality they have flocked together as they had once upon a time and again later in a deserted region, a camp in the open, a countless number of men, an army, a people, under a cold sky on cold earth, collapsed where once they had stood, forehead pressed on the arm, face to the ground, breathing quietly. And you are watching, are one of the watchmen, you find the next one by brandishing a burning stick from the brushwood pile beside you. Why are you watching? Someone must watch, it is said. Someone must be there.

Kafka, “At Night”