The Legitimacy of the Modern Age covers a lot of ground, but one of the central theses, and the one that bears little resemblance to most prior theories of history, is this one:

The modern age is the second overcoming of Gnosticism. A presupposition of this thesis is that the first overcoming of Gnosticism, at the beginning of the Middle Ages, was unsuccessful. A further implication is that the medieval period, as a meaningful structure spanning centuries, had its beginning in the conflict with late-antique and early-Christian Gnosticism and that the unity of its systematic intention can be understood as deriving from the task of subduing its Gnostic opponent.

Legitimacy, p. 126

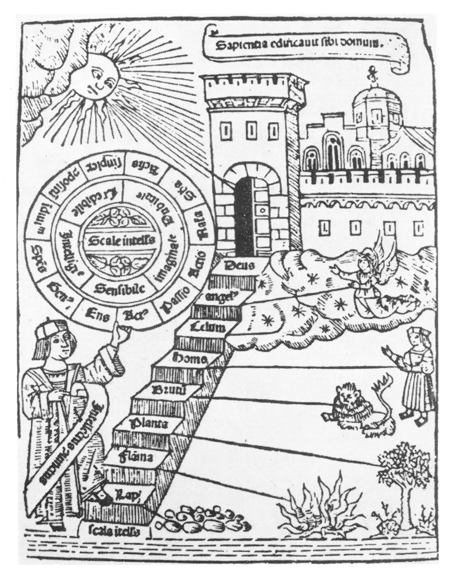

The first issue is what exactly Gnosticism is. It’s a term that’s been held up over a lot of heterogeneous (and usually heterodox) doctrines, and the closest Blumenberg comes to defining it concisely in the Christian context (for that is his major concern here) is that it is the thesis that knowledge is salvation. But in the larger scope of the book, the conflict between Gnosticism and its enemies–first through Augustinian-derived Scholasticism, and then through secular, scientific modernity–is best summarized as a conflict between hermeticism and worldliness.

That is to say, Gnosticism challenges the ability of a person to make meaning out of anything on earth, arguing that God’s sheer unknowability and the ultimate contingency and unreality of this life make meaningful action in this life not just difficult, but impossible. As with other hermetic doctrines of the past, and here Blumenberg not only invokes stoicism, but also skepticism and Epicurism (all of which, he maintains, preach a turning away from worldly curiosity because such things will never provide happiness for humans), knowledge of the world such as that provided by science is not real knowledge. The real knowledge is gained through turning inward and seeing through the illusions of our reality.

In turn, Augustine and the ensuing Scholastics say no, our actions do matter: we are given free will to sin or not sin, and those actions are of a consequence beyond anything in this world. This is a limited form of re-engagement with the world, as it does not provide a mandate for full engagement with the world, but only for behaving according to specified rules. The fissure left between virtuous behavior and the rest of reality is where the problems with the medieval “solution” arise. The problems of theodicy–those of justifying God’s ways in this world, including the presence and purpose of humanity–have not been solved, and so the seemingly arbitrary ways of the world cause a retreat to Gnosticism.

Gnosticism returns within Scholasticism in the form of nominalism, that is, the idea that God is beyond all explanation and law. As Aquinas, Ockham, and Nicholas of Cusa try to make their cases for Catholic doctrine, the ultimate lack of explanation reasserts itself. No law is sufficient to capture anything that God may or may not dictate, and so the guarantee of salvation is put into question.

Now, modernity, and specifically a secular scientific curiosity, begins to emerge to fill in the gap. In the absence of a justifiable mandate or explanation from God as to humanity’s presence in the world, the idea of secular self-assertion originates, carefully using the space created by shunting God far, far away from this world to justify an incremental, trial-and-error ideology and methodology for gaining mastery over the world for their own benefit. The problem that Gnosticism posed that the Scholastics could not satisfactorily answer–what is the meaning of the suffering and evil in this world?–gets a new answer: it is for humanity to master and overcome.

[I am being a little loose with the terms “world” and “earth” here, for Blumenberg makes the Copernican abandonment of geocentrism and the ensuing shift in the conception of the “heavens” the fulcrum point that tips the Middle Ages into modernity. But leave that aside for now.]

Here is Odo Marquard’s summary of this basic sequence:

Marcion believed that the only way for humans to be saved from the evil world was by an entirely different, unworldly redeemer god, a god who, battling with the world’s evil creator, destroys it in a redeeming eschatology. As a world-conserving age, the modern age opposes this: It is (as Hans Blumenberg says) an “overcoming” of Gnosticism, the “second” overcoming, in fact, because the first one–the Middle Ages–proved unsuccessful. The first, medieval refutataion of Marcion was the discovery of human freedom by Origen and Augustine, by which (as God’s alibi) all the world’s evils are imputed, morally, to man, as his sin, so that the principle that “omne ens est bonum” [all being is good] can continue to hold in respect of God. This first refutation of Marcion is finally retracted by nominalism’s intensification of the theology of omnipotence and by Luther’s doctrine of the servum arbitrium [subject will]. In this way, the creator god is again burdened with the world’s evils. He evades this burden…so that human beings have to dispute–ultimately in a bloody manner–about questions of salvation…The schatology of redemption has to be neutralized. This neutralization of the eschatology of redemption is the modern age. For if the modern age is to be possible, the urgency of redemption must be removed by an attempted demonstration that this world is endurable, even in the absence of the saving end, thanks to many a “rose in the cross of the present”; in other words, its creator was not a wicked god, and the world is not an evil world.

Odo Marquard, “Unburdenings”

This is ultimately a rather Whiggish argument, and there’s no question over the course of the book that Blumenberg believes that on balance such self-assertion is a good thing. He opposes it to conservative polemics that things used to be so much better when religion was around, implicitly arguing that things were so inexplicably awful during such superstitious times that modernity at least offers the will to overcome that wretchedness. And consequently, if theodicy had been so successful at countering angst over the world, why has it never provided an adequate answer? (To these inadequate answers, he adds those of Heidegger, Schmitt, and others like Levinas.)

The hermetic impulse persists today in the myriad new age trends that pledge distance from worldly affairs, assorted Pyrrhonist and stoic philosophies, and the general fear that the paths of self-assertion have not quite worked out as their early proponents (Bacon, Diderot, etc.) had promised. One particularly bizarre variant is transhumanism, which promises an entire new world achieved through technology. (Is this perhaps an echo of Eduard von Hartmann, who urged the elimination of the evil Schopenhauerian Will through technological advancement?) It’s an understandable impulse. Blumenberg repeatedly cites the failings and failures of what he terms modernity, but beyond legitimate, worldly modernity reluctantly seems to be preferable to the alternatives.