![themarriage[1]](http://www.waggish.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/themarriage1.gif) A few years ago, Rod Humble wrote a short, abstract game called The Marriage. The action consists of trying to get two squares not to shrink or fade out while circles drift around them. You control the blue circle. The pink circle is not under your direct control.

A few years ago, Rod Humble wrote a short, abstract game called The Marriage. The action consists of trying to get two squares not to shrink or fade out while circles drift around them. You control the blue circle. The pink circle is not under your direct control.

But the game interests me less than the rhetoric of Humble’s explanation for the game. I really am not picking on Humble here, who seems like a reasonable person. It’s just worth observing how utterly foreign his analogical mindset is from that of the best writers.

He wrote the game in an attempt to get away from concrete, visual representation of ideas and concepts, yet what resulted was something conceptually very concrete.

Here is his interpretation that guided the game’s construction:

The game is my expression of how a marriage feels. The blue and pink squares represent the masculine and feminine of a marriage. They have differing rules which must be balanced to keep the marriage going.

The circles represent outside elements entering the marriage. This can be anything. Work, family, ideas, each marriage is unique and the players response should be individual.

The size of each square represents the amount of space that person is taking up within the marriage. So for example we often say that one person’s ego is dominating a marriage or perhaps a large personality. In the game this would be one square being so large that the other one simply is trapped within the space of it unable to get to circles and more importantly unable to “kiss” edge to edge.

The transparency of the squares represents how engaged that person is in the marriage. When one person fades out of the marriage and becomes emotionally distant then the marriage is over.

Your controls reveal the agency of the game. You are only capable of making the squares move towards each other at the same time or removing a circle by sacrificing the size of the pink square. You are playing the agency of Love trying to make the system of the marriage work. Not only does this mean that the mechanics of attraction and sacrifice communicate love but also the physical way the game is controlled, I wanted a gentle almost stroking like feel to playing the game, that’s why clicking or rapid motion was not appropriate.

The backdrop’s colour has meaning. It starts off blue representing the world of the masculine. The club scene perhaps or adventures and exuberant experimentation. It then over time transitions to purple a mix of blue and pink representing the beginnings of a more permanent relationship. Then to pink as we enter fully the world of the feminine such as a home made together or emotionally the relationship becoming more kind. Next onto green colour of life and renewal, this represents a giving back to the world by the marriage, perhaps creatively, perhaps by having children or caring for others. Finally it becomes black symbolizing that at the end of the marriage when life is done there is nothing but each other. The only break in the blackness is at the bottom, where the strip of light representing memories of the marriage has been built up.

The game mechanics are designed such that the game is fragile. Its easy to break. This is deliberate as marriages are fragile and they feel fragile, I wanted to get this across.

The final part of the game comes if the marriage ends while the backdrop is black. At every point the two squares have kissed during the game a pair of tiny squares is created and drift off the screen, as the last one leaves the game ends.

Now, without getting into heavy analysis, some points should already be clear.

- The incredible literalness of the mapping from game elements to concepts.

- The stripped-down simplicity of the conceptual vocabulary in order to allow for such a literal mapping.

- The received nature of the concepts, taking stereotypical notions like the blue masculine and the pink feminine in order to obtain an easily-grasped mapping.

(In 1910 pink was considered a very masculine color, so the symbols are culturally relative, but some relatively common symbol set within a community must always exist, and is probably always trite by its very nature.)

None of these are inherently bad tendencies. In many ways, they are necessary ones for making playable games. But the risks and problems of applying such an ambiguous conceptual vocabulary onto a literal representation should be apparent as well. It encourages a fallback onto the most common of common knowledge in order to make such a mapping comprehensible. Subjective metonymy within a simple framework (the “stroking feel” being linked to love, the various meanings of all the colors) is the key dynamic at work.

But it’s not even the particular symbols used (pink feminine, blue masculine), so much as the need for such a simple framework itself. Let’s say we need two things in a game to represent the male and the female. Is there anything satisfactory that isn’t either reductive or opaque?

- The Mars and Venus gender symbols

- Sword and pillow

- Square and circle

- Drum and cymbal

- Hot dog and donut

The use of pink and blue didn’t produce a more sophisticated set of symbols, just a less blatant set. The metonymy was at the same concrete level as any of the duos above. And it applies to metonyms like the transparency equating to engagement.

It is the mindset of a Gene Wolfe, then, where every element, no matter how obscure, has a single definite meaning, rather than the mindset of a James Joyce, where the embrace of ambiguity and contradiction on lexical, semantic, and structural levels yields greater riches than a single postulated meaning.

My contention is that this sort of Platonic, atomistic thinking goes hat in hand with the sort of thinking used in constructing and utilizing scientific models of the world, as opposed to the messier business of human language and human relationships where a far greater degree of ambiguity is both acceptable and accommodated. This ambiguity inevitably leads to misunderstanding, sometimes destructively (say, in a marriage). The question is whether sufficient clarity can be achieved without adopting such a reductive, game-like model. Otherwise, you’ve adopted a view of the world (or of love, or of a marriage) that could easily fail you.

Ironically, this is the sort of analysis often performed in literary criticism. Thomas Karshan’s recent article on Nabokov in the TLS quoted this scabrous response from Nabokov in response to W. W. Rowe’s finding sexual innuendos in Pale Fire such as “wick” in “wickedly folding moth”:

The various words that Mr. Rowe mistakes for the “symbols” of academic jargon, supposedly planted by an idiotically sly novelist to keep schoolmen busy, are not labels, not pointers, and certainly not the garbage cans of a Viennese tenement, but live fragments of specific description, rudiments of metaphor, and echoes of creative emotion. The fatal flaw in Mr. Rowe’s treatment of recurrent words, such as “garden” or “water”, is his regarding them as abstractions, and not realizing that the sound of a bath being filled, say, in the world of Laughter in the Dark, is as different from the limes rustling in the rain of Speak, Memory as the Garden of Delights in Ada is from the lawns in Lolita.

Vladimir Nabokov

Nabokov appeals to a hermeneutic holism that defeats such easy metonymic models. It’s not that the richer worlds of which he speaks cannot be quantified as such, just that the vocabulary required is so dauntingly extensive as to require lived human experience. No such sophisticated symbolic model for this experience yet exists, and I don’t see one coming any time soon. A model cannot capture the live fragments of which Nabokov speaks. When rendering such fragments in a game, the abandonment of complexity disguises itself by using a sufficiently obscure model, so that the model does not seem banal.

Nabokov hated Freud and psychoanalysis (hence the veiled reference to Vienna), and indeed, this sort of atomistic symbolism makes me think of something Ernest Gellner said about psychoanalysis in The Cunning of Unreason: the psychoanalytic model had to walk the line between scientific precision and mythical ambiguity so as not to seem banal or spurious.

A purely hermeneutic psychoanalysis would not sound like science, confer no power, and few men would turn to it in distress; a purely physicalist or biological psychoanalysis would have been too much like a science, and no fun. But the plausible-sounding fusion of both is very different, and most attractive.

Ernest Gellner, The Cunning of Unreason

And weaker writers rely on exactly this careful navigation between the Scylla of simplistic allegory and the Charybdis of pointless ambiguity, so that they may seem profound when they really are not. I am thinking her of Alberto Moravia’s endless rationalism, where there is a neatly placed psychological explanation for every character trait and every movement proceeds from the careful arrangement of forces logically arrayed. (See The Conformist.) Moravia does it so well that the ultimate weakness of construction is a shame. (Removing the explanations, as was done in the wonderful movie of L’Ennui, can produce amazing results.)

I know: The Marriage is just a game. Humble did not mean to make any sweeping statement about marriage in general, and the game is clearly so personal to him that I feel a little bad using it to exemplify a certain type of thinking. But speaking just personally, if my partner wrote this game and explained the game to me in that way, I would be frightened out of my wits.

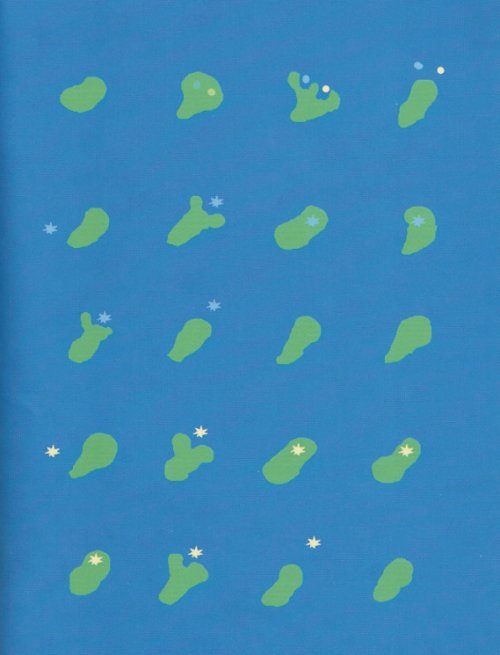

Update: Rod Humble has responded kindly in the comments, and I appreciate his openness to discussion and critique. I also wanted to point out Derek Badman’s essay on Lewis Trondheim’s Bleu, since comics rely on the sort of abstracted narrative visual representation that games do as well. Bleu “tells” of the interaction of a green blob with two stars and two dots. To the best of my knowledge, there is no “key” to the abstraction. Yet the similarity is striking!