Albert Hirschman was an amazing writer and his three slim books written for a general readership make their points with incredible efficiency. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty is incisive about the individual’s relationship and loyalty to a provider or employer. The Passions and the Interests is an excellent history of why capitalism seemed like such a savior when Adam Smith and others were promoting it, and how those arguments have persisted and mutated.

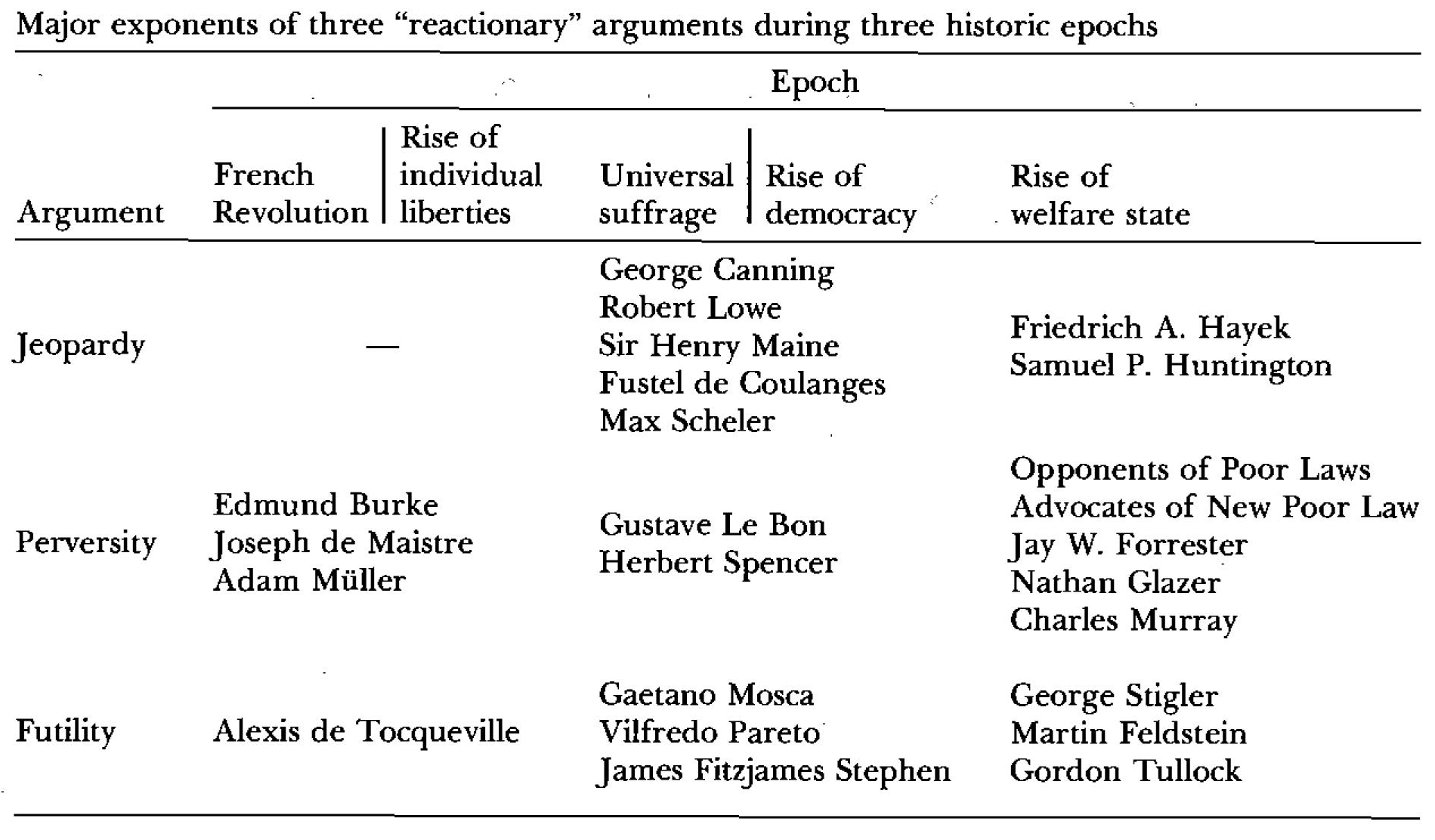

The Rhetoric of Reaction is a bit more diffuse and abstract than those books. It is at its best when most concrete. Hirschman, an admitted progressive, examines reactionary and conservative arguments of three types:

- According to the perversity thesis, any purposive action to improve some feature of the political, social, or economic order only serves to exacerbate the condition one wishes to remedy.

- The futility thesis holds that attempts at social transformation will be unavailing, that they will simply fail to “make a dent.”

- Finally, the jeopardy thesis argues that the cost of the proposed change or reform is too high as it endangers some previous, precious accomplishment.

(These do map uncannily onto my own Three Versions of Conservatism. The mapping is Elitist Conservative : futility :: Sentimental Conservative : jeopardy :: Cynical Conservative : perversity.)

I think the three theses do not in fact cleave as cleanly as Hirschman wants them to. Futility is something of a lesser version of the other two, as any action that is useless can then easily be portrayed as wasteful or dangerous. Futility often exists as a fallback position: “Well, if welfare won’t make people more poor, and if it isn’t in fact a huge waste of money…it still won’t do any good!” Hirschman points out that switching rhetorical strategies, no matter how incoherent, is extremely common.

Hirschman pronounces the Perversity thesis “the single most popular and effective weapon in the annals of reactionary rhetoric.” I agree, and it dominates the book as well. I think Hirschman misses one significant reason why it is more successful than jeopardy. (Futility is less hyperbolic and scary than the other two and so easily loses out.) Jeopardy is multidimensional, while perversity is monodimensional. Jeopardy requires one to think about trade-offs between two or more separate but interdependent axes of goods and values, while perversity simply argues that we will go the wrong way along a single axis.

Perversity’s simplicity is its strength. Far more efficient to argue that welfare will make people poor, that affirmative action will disenfranchise minorities, that antitrust will destroy competition. Simple, elegant, and utterly specious.

Consequently, the Jeopardy thesis is more intellectually interesting, even if it’s been less ubiquitous. Hirschman has some great quotes from the 19th and 18th centuries arguing that giving people the right to vote would endanger people’s liberty. The same neocons who tell us how we should be aping Athenian democracy today are reversing the same pattern used by Fustel de Coulanges in 1864, who said that the democracy of Athens was only possible through a complete absence of what we call liberty. Now, according to Kagan and Smith and Hanson, democracy is only possible through an increasing absence of liberty. For Fustel, Greece was a scary bogeyman; now it’s an unreachable ideal. Same rhetoric.

And through this handy chart that Hirschman gives, we see that some of the neocons and racial “scientists” of today are the same people who were arguing against welfare decades ago, using the same rhetoric:

Hirschman also critiques progressive rhetoric for having too sunny a view, but despite his claims of even-handedness, he seems to be a lot harder on the reactionaries. Maybe this is just my own bias: optimism about bringing liberty, suffrage, and welfare to those lacking it seems far less offensive than attempts to prevent those efforts.

Still, while Hirschman treats Tocqueville and Scheler with some respect, the others come in for well-deserved contempt. It is always good to be reminded of what a horrible person Pareto was (Mussolini supporter, anti-democratic, draconian Social Darwinist); isn’t Pareto-optimality just another statement of the Jeopardy thesis?

Hirschman seems to agree, but he does point out the danger of the progressive/radical “desperate predicament” strategy, which rhetorically argues that things are so bad that any cost is justifiable as long as it brings about change. The more conservatives argue the danger, the more they argue that there are never legitimate grounds for change, the more it pushes radicals to say that the danger is necessary and justified.

Hirschman concludes that Burkean arguments actually radicalized progressives in the 19th century, inducing them to portray current conditions as more hopeless and more desperate than they would have otherwise. I don’t know if the link is quite so direct. I think that the French Revolution itself did force progressives to look at the potential costs of revolution more closely, and that itself may have helped to radicalize the rhetoric.

Yet ultimately it is the bad faith of the reactionaries that dominates, and Hirschman quotes Charles de Rémusat’s devastating critique of Burke’s blind worship of tradition to show just how empty such rhetoric is:

If the events, in their fatality, have been such that a people does not find, or does not know how to find, its own entitlements in its annals, if no epoch of its history has left behind a good national memory, then all the morals and all the archeology one can mobilize will not be able to endow that people with the faith it lacks nor with the attitudes this faith might have forged . . . If to be free a people must have been so in the past, if it must have had a good government to be able to aspire to one today or if at least it must be able to imagine having had these two things, then such a people is immobilized by its own past, its future is foreclosed; and there are nations that are condemned to dwell forever in despair.