Shohei Imamura (1926-2006) is, for me, one of the greatest filmmakers, possibly the very greatest, with films like Pigs and Battleships, The Insect Woman, Eijanaika, and especially The Ballad of Narayama being some of the most unflinching and incisive depictions of the struggles of the wretched of the Earth ever filmed. (On his death, I wrote an overview of Imamura’s major films.)

I had seen some but not all of his documentary work. More rough visually, the documentaries still make Imamura’s obsessions quite clear and are as crucial as his fictional films. I am very happy that Icarus picked up six of them (the incredible History of Postwar Japan as Told by a Bar Hostess (1970) is sadly not included) which will be showing at Anthology Film Archives next week. They are stunning. Imamura’s genius for extracting and showing the overlooked and filthy parts of human existence is always at hand.

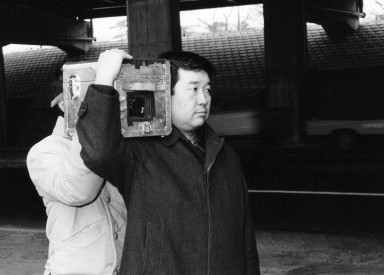

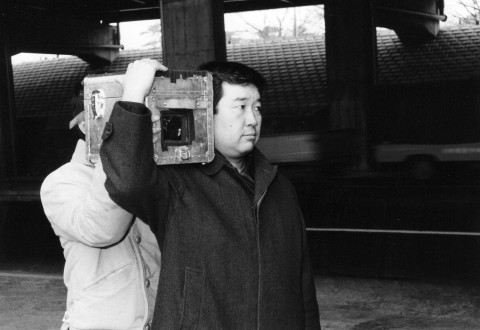

A Man Vanishes (1967) is the most bizarre and cinematic of the lot, one of the first documentaries in which the filmmaker is not just a hidden presence but an active participant. (A friend enjoyed the movie but found it contrived, because she hadn’t realized that it was a documentary at all.) Imamura sets about exploring the case of a Japanese businessman who has disappeared from his home, his work, his fiancee, his life. The documentary was commissioned with the expectation that they would find the man, but Imamura realized two things: first, they would not be able to find him, and second, he had clearly disappeared because his fiancee, Yoshie, was fairly unbearable.

But this was hardly sufficient for the movie, so Imamura changed tactics, focusing more on Yoshie and on the process of making the documentary itself.

I always try to talk to people myself as much as I can. That can get boring sometimes. I sense that there’s something that needs to be explored further behind what they’re saying. While making A Man Vanishes, my crew and I stayed in the room next door to Yoshie Hayakawa for a whole year. She had every imaginable bad quality, and none of us could really stand her. And yet I wanted to understand why I found her so disturbing, and that was enough to keep me going.

Imamura does not broadcast any of his opinions about Yoshie, however, instead retaining the pretense that the man’s disappearance is a puzzle and using the situation to capture more aspects of Yoshie, who is far more fascinating than the purported story.

Imamura begins manipulating events, instructing the “detective” (actually an actor) to spend more time with Yoshie as she seems to be falling for him, and staging several scenes. It is left unclear to what extent these interactions are scripted; even Yoshie at times seems to be aware of what is going on. Yoshie does not become likable but neither is she repellent. She’s a symbol of certain contemporary processes in Japan that remain unclear but disturbing.

The result is not merely forward-looking but bizarrely ambiguous both in content and tone. Peter Watkins was working in similar territory but A Man Vanishes is much weirder.

The remaining films are all more straightforward documentaries concerned with “serious” subjects. Rather than the bourgeois subjects of A Man Vanishes, they all focus on outsiders and the oppressed. Imamura’s sympathy with them is blatant. Equally obvious is his disdain for the “normal” society that mistreats them and then forgets about their existence.

Karayuki-San, The Making of a Prostitute (1975) is a documentary of Kikuyo, a Japanese “comfort woman” who was tricked into going into Malaysia in the early part of the century to be in service in Japan, only to end up working at a Japanese brothel there. Japan has entirely forgotten her. Now in her 70s, She has carved out a living for herself in Malaysia and lives with her stepson, her husband having died. Though she speaks cogently and stoically, her friends tell Imamura that she is far less happy than she seems and is mistreated by the family. Her fortitude and calm are tremendously impressive; the injustice and inhumanity of what has been done to her is suffocating.

In Search of the Unreturned Soldiers in Malaysia, In Search of the Unreturned Soldiers in Thailand (both 1971), and Outlaw-Matsu Returns Home (1973), each 50 minutes long, form a trilogy. The low-key titles belie the anti-authoritarian ethic at work: Imamura wants to find those who were enlisted by their country to fight, die, and murder on its behalf, and then abandoned. The latter two, in particular, contain some quintessential Imamura moments as unsettling as anything in his work.

Malaysia is the most synoptic, discussing the Sook Ching massacre of thousands of Chinese, Indian, and Malay by Japanese soldiers in 1942 and the residual tensions. (An apology has never been issued.) Imamura declares that he feels tremendous shame hearing about the residue of such events. He gives the most time to a soldier A-Kim, who has moved into a wholly Malaysian community and converted to Islam. His interview is the centerpiece of the documentary:

The Malays think the Japanese are a disadvantaged people. The Japanese work very hard and are tough. Always achieving one’s goals. But as for religion, we are very poor. All the good people will die. Those who survive will not be Muslims. Women will be walking the streets naked and most of the men will be dead, because of all the battles and war.

Muslims only follow one god. In Japan there is the Emperor. It’s the same in every country or the world. Whether it’s the king or the emperor, Muslims will not follow them. Because in the end, all leaders and even citizens are human. And humans cannot help other humans. What the emperor says sounds really nice. ‘Follow me, then you will be happy.’ But you don’t really know if that’s true. Every human has two sides in his heart. One is goodness or justice. The other side is greed. Japanese people were tempted by greed. That’s why the war began.

I know now as a Muslim, Christians and Muslims do not rush into things. We are much more flexible, and we take lots of time to think before we take action. That is how the Muslims are like by nature. Japan is now a huge industrial country. Right when the Pacific war began we forced ourselves on to enemy lands in one step. That’s how I see it. I think one day Japan will have to pay for it. That is my personal opinion which often gets me worried. When that time comes I think the Japanese will all suffer.

Imamura says: “He must have come to his ideas on war not just as a Muslim but as an individual whose entire youth was stolen by war.”

In Thailand, Imamura hit gold: three soldiers of widely differing temperaments discuss their experiences with each other, often contentiously. Most of the film is devoted to the gripping and revelatory conversation between Fujita, Toshida, and Nakayama.

Fujita, from Kyushu, is a farmworker and ardent nationalist, bemoaning Japan’s loss and intolerant of any criticism of the Emperor. He collected thousands of dead soldiers’ fingers to bring home to widows in Japan, only to be told to stay in Thailand for 13 years, after which Japan would return for him. (That did not happen.) He also tells openly of war crimes:

Chinese children had to be killed. I must have done 30,000 of them. I put them in a concrete hole and poured oil and burnt them alive. I couldn’t help it. It wasn’t about good or bad. If I didn’t kill them, I would have been killed. That’s how it was. I was a man born wild in Kyushu. I had to do what I had to do. So I killed them.

Those men with ranks, they’d have lots of money coming from somewhere. What right do they have to have mistresses? They raped the women and forced them to be mistresses. Those men were a disgrace to the Japanese army.

I’m hoping the younger generation will become more respectable with a strong Japanese spirit like the old generation. The basis of the Japanese spirit is, put simply, honoring the Emperor. We must be loyal at all times.

The other two are doctors, with little else in common. Nakayama remains silent for much of the film, though he tries to get Toshida removed at one point, and he comes across as fairly scummy, someone who has lived for himself without much care for others.

Toshida, however, is an irreverent, impassioned, and empathetic doctor who has turned pacifist, assimilated into the Thai community, and is aghast at the horrors of the war. He anticipates the title character of Imamura’s later Dr. Akagi (1998), the single-minded doctor only concerned with helping the sick and unfortunate, one at a time.

Toshida is tormented, though: he describes his war experiences, saying it has ruined his life.

I was in the guardhouse for disobedience. They forced me to do things that didn’t make sense. So I tried to escape. It made me hate my own country. Its stupidity. Nothing ever made sense.

Toshida listens sadly to Fujita, saying little, but seems more angry with Nakayama for neglecting his duties as a human being:

The greatest people are those who live and feel as a human. You might not understand this now, but you will soon.

I’m saying justice is greater than the Emperor. If you want to live an honest human life, you need to see things clearly. Do you understand? Do you?

Nakayama is like, “Banzai Emperor.” He’s an idiot! Idiot! I wish he’d use his brains and think.

[To Nakayama] You really need to think. Money has nothing to do with living a good life. It’s not about having more money than you need. You need to rethink humanity. I don’t take money from poor patients. They just thank me. I don’t take money from the poor. That’s inhuman. Even if it means my loss. You should travel through the countryside of Thai.

Toshida laughs that the other two are upset that he’s abusing the Emperor. Fujita simply tells Imamura: “If we were still soldiers, I’d kill him.”

Outlaw-Matsu Returns Home is about Fujita. (Outlaw-Matsu is Imamura’s nickname for him.) After Thailand, Imamura kept in contact with Fujita and helped reconnect him with his family in Japan, so that he could return home two years after the first documentary, only to find a horrible family drama there.

His parents and the family of one brother died in Nagasaki. One brother, Fujio, and sister, Fujiko, survive. Fujiko is divorced from her alcoholic second husband and has difficulty supporting herself and her children, but Fujio now refuses to help her, and has even hit her over things like failing to say “Hello” to him. Fujio has grown cynical like Nakayama, but as the documentary continues, far more ugly dealings come to light, to the point where Fujita told Imamura that he was going to kill Fujio.

Imamura says flatly: “Fujio had joined with the people who abandoned others.”

But Fujita is at the center, holding on to outdated notions of honor that lead him in two wildly different directions: family loyalty toward Fujiko, but toward strident nationalism. Imamura makes this paradox comprehensible as the tragedy of a person whose ideas of good and evil have been so wrenched from him that he can no longer wholly accept them nor reject them.

He tells Imamura in one unguarded moment: “I’m looked down on wherever I go. Even my brother looks down on me. I’m so confused.”

Yet nonetheless he rages against Fujio as he did with Toshida for disrespecting the Emperor. Imamura provokes Fujita (ingeniously, it must be said) by bringing him to the Imperial Palace, where Fujita is finally able to articulate his own confusion:

He lives in such a big palace. He doesn’t consider our hardship at all. So I didn’t want to come. Take him as your father. We gave up our real parents and considered the Emperor as our real father. Then why must he abandon his children? If we’re left in foreign countries, he ought to bring us back home. To show us how developed today’s Japan is. That’s only human. That’s how an Emperor or Minister should be. How can he be so arrogant, living in his own palace? An emperor should sell his own house if he has to rescue us.

IMAMURA: You got terribly mad when Fujio abused the emperor.

That’s because I’ve the right to abuse the emperor. But Fujio was in Japan. Abusing the Emperor is like him throwing mud at his own father. I may well have complaints against the Emperor. We were at war for several years. Nobody cried ‘Hurrah for the Emperor’ when they died. Now I understand why Japan has developed so much. The war was for money, wasn’t it? The Emperor must have started the war because he wanted money too. I think Japanese people are all insane with greed. That’s how I feel.

They’re all thriving on greed. They’re such big fools. They’re crazy, because they don’t have peace.

The complexity of Fujita’s feelings and psychology defies any easy conceptualization. Such insights, Imamura suggests, are available far more to the outcast than to the mainstream of society.

What remains unsaid in this film is the accounts of the horrors of war, which still remain out of Fujita’s reflections, which do not seem even to trouble him. When he speaks to another injured soldier from his troop, he emphatically says, “I’d like to join the Third Operation to kill the English or the Chinese again.”

I think Imamura was right not to press him on it. Toshida only pushed him into a more defensive and reactionary position. Taken on his own terms, Fujita remains a disturbing figure, yet his care for his sister is as genuine as his nationalist hatred.

So Imamura makes sure there are no clear lessons to be drawn, only brilliantly assembled portrayals of the mixture of atrocity and tenderness that constitutes humanity. And what could be learned from these portrayals is being ignored. Imamura concludes, “What I see are heaps of abandoned people as the super-express train Japan speeds away.”